Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

The poorest are worst hit

It is clear that the Covid-19 pandemic is nowhere near over, and that its impacts, and some of the policies put in place to address it, will be felt for many years. While attention has rightly been drawn to those who have been slipping back into poverty, those who were already the furthest behind, lacking even the most basic of assets, find themselves particularly badly affected. To dig deeper into some of the issues faced by this group, members of the Alliance2015 initiated a series of surveys in 25 countries in late 2020 and repeated the exercise in 18 countries over a two-month period between March and May 2022. The survey drew on programme participant lists from Alliance2015 member organisations. While this means the data is not representative of the entire population in the different countries, it potentially reflects the perspectives of the worst-off members of society. The tool used contained 89 questions and was administered using computer assisted personal interviewing techniques. It was designed to draw out information on the financial impact of the pandemic and changes in food security, health and education. The 2022 survey had 8,461 respondents, 55 per cent of them female; 30 per cent were under 30 years of age and 61 per cent between 31 and 60 years. Slightly over two thirds (69 %) lived in rural areas, 20 per cent in urban and 11 per cent in peri-urban areas. Just under one in ten described themselves as living in a camp setting. In terms of the households’ primary source of income, agriculture dominated (with 48 % of respondents giving this response), followed by petty trading and casual trading (16 % each). Key findings from the survey are summarised below.

More than half in worse financial situation

Our research included questions on people’s ability to earn an income, their perception of changes in the price of food, and the quantity and quality of food available to them, since the start of the pandemic.

Describing the change in the financial situation of their household since the start of the pandemic, 36.7 per cent of the respondents said that it had got a little worse, with 27.1 per cent claiming it had got a lot worse, while slightly more than one in eight felt that their situation had improved (14.2 %). (In late 2020, 34.6 % of respondents said the financial situation of their household had declined slightly, with 38.8 % saying they had experienced a significant negative change.) We see a greater proportion of those living in peri-urban areas (31.6 %) saying the financial situation of their household had got a lot worse since the start of Covid (in rural areas 27.1 % gave this answer, while in urban areas 24.5 % did). Similarly, those who depended on external support from government or NGOs (45.2 %) or on casual labour (35.1 %) as their main source of income were more likely to give this response than those in formal employment (22.6 %).

The country where the greatest proportion of respondents said that their household’s financial situation had got worse since the start of the pandemic was Bolivia (86.6 %), although over three quarters of respondents in the Central African Republic (CAR – 76.1 %), Peru (76.6 %), Syria (82.3 %) and Zambia (77.5 %) also gave this response. The lowest proportion of respondents identifying the situation had worsened was in Honduras and Chad – although this may be a reflection of their precarious pre-Covid financial position.

Almost two thirds (66.3 %) of all respondents said that Covid-19, and related restrictions, had created difficulties, or challenges for how their household currently earns an income. This can be seen across all occupations, settlement types, gender and age groups, although it has particularly affected those living in peri-urban or camp setting and those dependent on casual work or petty trade.

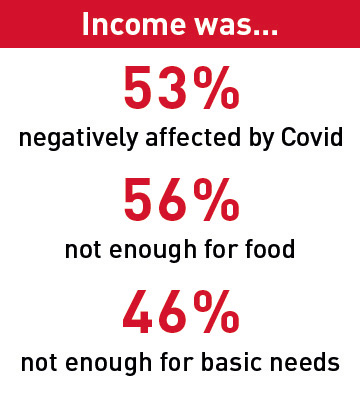

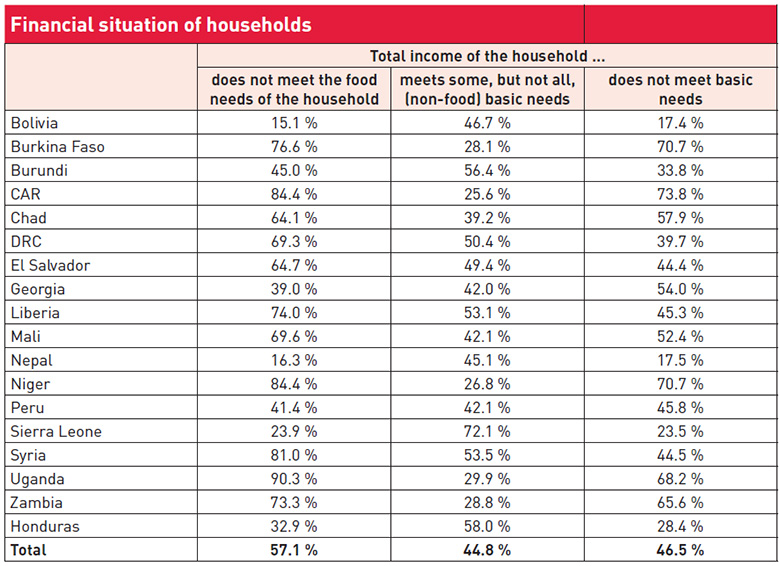

We also asked respondents whether the total income of the household met its food needs and other basic needs such as housing, transportation, health and education. Overall, 57.1 per cent of respondents said that their income was not sufficient to meet their food needs, 44.8 per cent that it was meeting some of their other basic needs, and 46.5 per cent that it was not meeting their basic needs.

These overall figures hide a huge variation between countries – for instance, in Uganda (90.3 %), Niger (84.4 %), CAR (84.4 %) and Syria (81.0 %), a vast majority say their income is not able to meet basic food needs of the household, while in Bolivia (15.1 %) and Nepal (16.3 %), a much smaller percentage of households report such distress (also see Table).

Huge challenges in accessing food

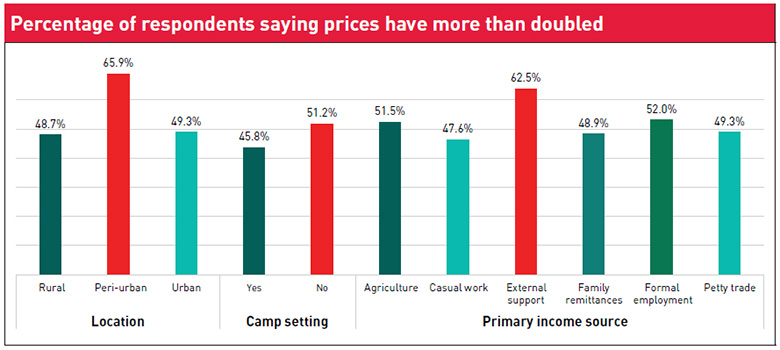

The survey followed-up by asking whether respondents had “observed any change in food prices since the Covid-19 crises started, and if so, what was the change?” Over half (50.6 %) stated that prices had more than doubled, with a further 28.6 per cent saying that they had increased by between 50 and 100 per cent, and 14.5 per cent maintained that they had increased by less than 50 per cent (also see Figure). Respondents living in peri-urban areas were much more likely to say that prices had more than doubled than those who lived in rural areas (65.9 % against 48.7 %). Those who depended on external support, such as that provided by government or other non-governmental actors, were most likely to say that prices had more than doubled.

Out of all those interviewed, just over two-thirds (67.8%) identified they had experienced other challenges in accessing food. The most frequently identified problem amongst this group was a reduced quantity of food available in the market, given by 53.9 per cent of respondents, followed by the reduced quality and variety of food available in the market (given by 32.7 %), and difficulties in accessing markets because of ongoing restrictions or fear of contagion (given by 32.6 %).

With challenges faced in terms of ability to earn an income and with the price of food as well as other challenges in terms of the availability of food in the market, the survey dug deeper into the question on whether the quantity of food consumed in the respondent’s household had changed since the start of the pandemic. Just under two in three of those interviewed (62.6 %) felt that their household was eating less. This compares to 40 per cent of respondents saying their household had reduced the quantity of food consumed in the earlier 2020 exercise. There are large variations across countries, with over 70 per cent of those interviewed giving this answer in eight countries – Central African Republic, Burundi, DRC, Zambia, Burkina Faso, Liberia, Uganda and El Salvador. Across all countries, respondents who described themselves as living in peri-urban areas or camp settings were more likely to say the quantity of food consumed by their household decreased than those living in urban and rural areas, or non-camp setting. This response was more frequently given by those whose primary income source was petty trade (67.4 %), than amongst those who depended on formal employment as their main income source (at 41.8 %).

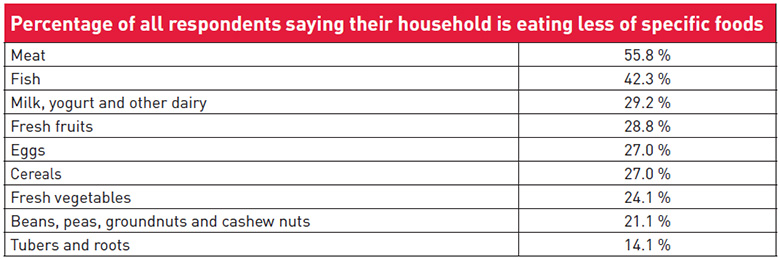

Respondents were also asked whether there were specific types of food their household was eating less of since the start of the pandemic. Amongst all respondents, the largest reductions were in terms of meat and fish, with 55.8 and 42.3 per cent saying their households had reduced their consumption of these foodstuffs, while 28.8 per cent said they were eating less fresh fruits and 24.1 per cent less fresh vegetables (also see Table).

We subsequently asked whether the respondents felt that the quality of food their household consumed had changed since the start of the pandemic. In reply, 51.6 per cent were saying that this had got worse – again a higher proportion than had given this response in the exercise carried out in late 2020, when 42 per cent said this was the case. Those who lived in peri-urban areas (59.8 %) were more likely to give this answer than those in rural (51.5 %) or urban (47.2 %) areas. Those in formal employment were less likely to say that the quality of the food their household consumed had got worse (31.2 %), when compared to those who depended on petty trade (53.8 %), agriculture (56.5 %) or casual labour (53.8 %).

We also asked respondents to think back over the past three months and identify whether there were times when they had to reduce food expenses to the extent that anyone in the household went to bed hungry. Overall, one third of respondents (33.4 %) said this had happened. This response was most commonly given in CAR (by 85.0 % of those interviewed), followed by Sierra Leone (58.4 %), DRC (56.2 %) and Niger (50.7 %). This response occurred more frequently among those living in peri-urban areas (40.2 %) than among those living in rural (34.3 %) or urban (26.8 %) areas; similarly those living in camp settings were much more likely to give this response than those who did not (48.3 % against 31.7 %). This response was least frequently given by those in formal employment (11.2 %), and most frequently by those involved in agriculture (38.8 %), casual labour (35.3 %) and petty trading (34.7 %).

Respondents were asked a further question to ascertain the regularity with which this was happening. Amongst those who responded “yes” to the previous question, 29.0 per cent said somebody was going to bed hungry at least once every month, with 43.3 per cent stating this was more than once a month. Again, it was in CAR where this appears to have been most severe, with 83.6 per cent of respondents saying that when this occurred, it was happening more than once a month. Of those who said somebody in their household went to bed hungry in the previous three months, 70.2 per cent said this was happening more frequently since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic. Amongst all respondents, the greatest proportion giving this response was in CAR (where 62.5 % said this had increased since the start of Covid-19), followed by DRC (where 46 % of all respondents gave this response).

With almost two-thirds of all respondents feeling that Covid-19 had created challenges for how their household currently earn an income, and over a half feeling that prices had more than doubled, it is no surprise to see that such a high proportion of people feel this has impacted on both the quantity and quality of food consumed, with the result that household members were going to bed hungry. While these difficulties are seen across all occupation groups, settlement types, gender and age groups, it has been particularly pronounced amongst those living in a peri-urban or camp setting with limited access to services, and those dependent on casual work or petty trade, who have less protection for their income.

Almost a third neglected healthcare visits

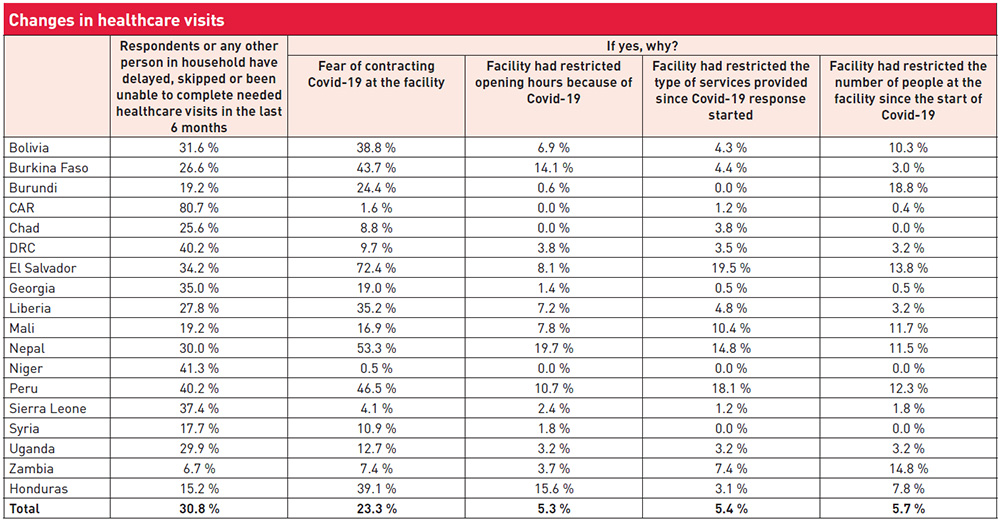

Respondents were also asked whether they, or any other person in their household, had delayed, skipped or been unable to complete necessary healthcare visits in the previous six months. Over 30 per cent (30.8 %) said this had been the case, with the highest share in CAR (80.7 %) and the lowest in Zambia (6.7 %).

When asked why certain health services were not availed of, those surveyed said that they were too costly (53 %), the facilities were too far or costly to get to (26 %), they were afraid of contracting Covid-19 at the facility (23 %), there were long waiting times (22 %), the facilities were understaffed (11 %), and there were restrictions on timing, or facility capacities were limited. While Covid-19 has undoubtedly affected people’s access to health services, many of these responses are indicative of pre-existing shortfalls in access or services that pre-date the pandemic. For instance, longer waiting times was the most frequently cited reason by respondents from Bolivia, Liberia, Peru and Zambia (also see lower Table.

The 30.8 per cent who responded that they had delayed, skipped or been unable to complete necessary healthcare visits in the last six months were also asked: “Which kind of assistance would you have needed?” These were in-patient care (37 %), followed by outpatient care (28 %) and Covid-19 vaccinations. Many respondents cited pre- or post-natal treatment as the next most likely healthcare service to be missed. The periods before and after childbirth are some of the most critical stages of life for both mother and child and are a significant factor for maternal and neo-natal mortality.

A “lost generation” in education

The impact of Covid-19 on schooling has the potential to be multigenerational, raising concerns about a “lost generation” in education. Unicef suggests that the current generation of students now risks losing 17 trillion US dollars in lifetime earnings at present-day values, the equivalent of 14 per cent of today’s global Gross Domestic Product (GDP), as a result of school closures. In low- and middle-income countries, due to the long school closures and the varying quality and effectiveness of remote learning, the percentage of children living in learning poverty will potentially rise to 70 per cent. The pandemic has significantly set back past progress in education. Young people who have missed out on schooling have also, in some cases, lost the opportunity to learn about their reproductive health rights, family planning methods and WASH (water, sanitation and hygiene). These deprivations would have long-term impacts on issues such as child marriage, pregnancy and infant mortality rates, too.

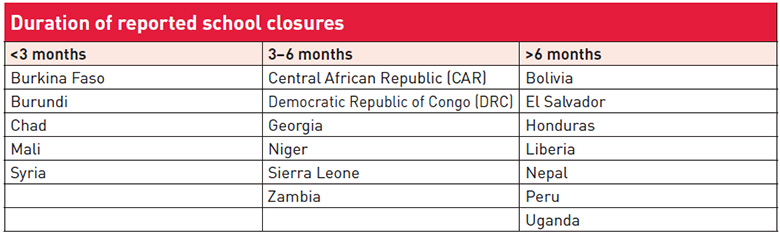

Respondents to this study identified that schools were closed for an average of six months due to Covid-19, with considerable variability in the responses (also see Table below). For example, respondents in Uganda reported children to be out of school for 22 months, during which time they received books and listened to radio programmes to supplement their learning. The proportion of respondents who said any of the children of school going age in their household had permanently dropped out of school since the start of the pandemic ranged from 5 per cent to 18 per cent, depending on the age group. However, in Syria, schools were closed for around two months, and the children’s learning was supplemented by other, unspecified means, while the proportion of respondents who said any of the children of school going age in their household had dropped out permanently was much higher, ranging from 21 per cent for children under 11 years to as high as 81 per cent for girls aged 16 years and above.

The survey identified whether there were boys or girls in the household of primary, lower secondary and upper secondary school age, and then if any of these children had permanently dropped out of school since the start of the pandemic. More children in the lower grades were likely to return to school, and there was little difference between the proportion of girls and of boys who had returned to school. However, older children were less likely to return, and this was more pronounced for girls at upper secondary level than for boys.

For children and youth at risk prior to the pandemic, the closure of schools may have exacerbated further inequalities that existed both within society and between schools which pre-dated the pandemic. Families with the fewest resources were unable to maintain consistency in their children’s learning when more pressing needs, such as maintaining a source of income, took precedence.

Only 45 per cent of respondents who had children of school-going age in their household reported that the children had access to any kind of learning support while they were at home from school. Of them, 48 per cent said the learning support was home schooling by parents or siblings, 41 per cent said they had access to digital or online learning, and 35 per cent used books provided by the school during the closures.

What needs to be done

The poorest and most vulnerable women and men have seen the pandemic and related restrictions worsening their economic situation. The survey once again shows that the most vulnerable people in our societies are exposed to multiple shocks simultaneously. While government programmes can offer support and alleviate suffering, these were often not accessible to the poorest due to mobility issues, lack of timely access to information or the use of complex technology to submit necessary information online. Looking forward, addressing this requires a concerted action by all actors, using all the instruments of engagement at their disposal, both short- and medium-term, such as strengthened safety net programmes, programmes designed to help children catch up on the education lost, and a renewed emphasis of agriculture and local economic development. Furthermore, a focus on inclusion would lead to the design of alternate approaches that leverage the presence of local institutions, actors, channels of communication and authentication. While digital technology has been a large enabler during the period of restricted mobility due to prevalent Covid-19 regulations, it has also resulted in the exclusion of many who are less familiar with its use while possibly most in need.

As well as prolonged school closures, additional interventions that typically target learners living in poverty, such as school feeding, safe transportation, and sanitation, all of which ease the financial burden on families and make the environment more conducive to learning, have seen some of the most extended disruptions. Among respondents who noted that the state of education got a lot worse, the top reason specified was that schooling was unaffordable because of their families’ financial circumstances. Services to reintegrate students and encourage dropouts to return to school need to be established and, where they have started, further strengthened. National budgets for education have to be adjusted, and measures must be implemented that help ease the financial burden on families.

We see a similar challenge in the health sector, where our results point to healthcare becoming unaffordable during the pandemic, potentially compounding pre-existing issues. In this respect, we call for attention to be placed on strengthening health systems overall, and in a manner that specifically addresses the needs of the most vulnerable women and men, addressing inequalities exacerbated by the pandemic. National Covid-19 recovery plans need to prioritise these actions with adequate funding, coordination, and alignment of aid.

The slight shift observed in people’s primary source of income, away from agriculture and formal employment to casual labour and petty trade, suggests people are being forced into more precarious sources of livelihoods, with large proportions of those interviewed unable to earn enough to cover their basic needs. As the survey was conducted before the start of the conflict in Ukraine and its impacts on world food prices, the situation is likely to have deteriorated further, and the outlook for 2023 remains bleak. While many of the survey respondents were positive about their short-term financial outlook, their hopes will be tempered by events over the past few months.

Against this background, it is essential for governments, donors and NGOs to continue to promote resilient, sustainable, inclusive and equitable food systems that put vulnerable people at the centre. This can be done through scaling-up support to community-led approaches that promote locally and regionally anchored food systems, and that are focused on the needs of vulnerable producers and consumers, while investing in initiatives that incentivise small-scale food producers, farmers, pastoralists and their organisations to become economically and ecologically sustainable producers.

Chris Pain is head of the technical assistance team in the Strategy, Advocacy and Learning Directorate in Concern Worldwide, based in Dublin, Ireland.

Contact: chris.pain@concern.net

Patrice Fyffe is an institutional fundraising expert with People in Need.

Paulo Rodrigues is a market systems development advisor, specialised in fragile contexts, in HELVETAS Swiss Intercooperation, Bern, Switzerland.

Rupa Mukerji is Director of the Advisory Services department in HELVETAS Swiss Intercooperation. Contact: rupa.mukerji@helvetas.org

Alliance2015 is a strategic network of seven European NGOs engaged in humanitarian and development action. For more information, see: www.alliance2015.org

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment