Read this article in French

Read this article in French

Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Children are losing hope

Cute was 16 years old when the first lockdown hit her life in the small town of Seke in Zimbabwe. “From one day to another, there was no income,” she recalls. “My mother sells vegetables in the small market, which is what we were living on. The market was closed down.” Cute is active in the Citizen Child Youth Media project. With the support of the child relief organisation terre des hommes, it is giving children and youths voice and enabling them to represent their interests. Cute reported on her situation for two years. In late 2021, she wrote that nothing had changed since the year’s first lockdown. “During the lockdowns, the schools were closed,” she reported. “Everyone was talking about online lessons. But for this you need a smartphone and money to pay for Internet access. For me and my fellow pupils, this is just an illusion, and I know that here, most young people are in the same situation. We simply can’t afford it. One year on, and online lessons are still unaffordable for most of us.”

Instead of learning, Cute helped with daily chores such as fetching water. She got up at four o’clock in the morning to join the queue by the well. She and her friends were afraid of catching diseases in the crowds of people. But this is the only way to get clean water in Seke. The wardens take advantage of the situation. “The men supervising the queues often demand sexual favours from us girls,” Cute says. “Then you can jump part of the queue. Those who don’t join in only have the option to spend what little money we have on water instead of food.” She mentions a further topic that is making life difficult for the girls. If the families run out of money, the girls can no longer buy sanitary pads. “I started a small survey when many of my friends said they couldn’t buy sanitary pads,” Cute explains. “I found out that nine out of ten girls couldn’t afford pads. In despair, they used any kinds of rags – unhealthy material. One might be looked down upon for pointing out this problem to the whole world, but for girls who are growing up, sanitary pads are an absolute must.”

Hunger took command in just a few days

Cute experienced the lockdowns during the pandemic aggravating already existing problems in just a few days’ time. “We’re in a desperate situation, and most children have lost all hope,” she says. “People the world over are speaking of lockdowns to avoid infections and possible death. But what is the point of this for children who don’t know whether there will still be something to eat tomorrow, and who are afraid of starving to death?”

The corona crisis has impacted on a situation in which billions of people do not have any protection against economic shocks for even a few days. The World Bank estimates that half of the households in developing countries and emerging economies are unable to afford food, water and housing costs for more than three months without income. However, among poor families who already had too little to live on before the pandemic, hunger set in after just a few days. Migrant workers and day-labourers, domestic staff and women factory workers lost their jobs overnight. Women smallholders were no longer able to sell their produce, for the markets were shut down and transportation forbidden. Neither was there any support from relatives working in the major cities or abroad. Only a minority of people world-wide can reckon with aid in the form of unemployed benefits or insurance covering health costs. Fifty-three per cent of the world population, more than four billion people, have no social security at all. None of these people had anything to counter the economic impact of the pandemic.

What we know about how the pandemic affects children …

Just like in any crisis, the most vulnerable groups of the population are those hit hardest: poor people, discriminated groups, refugees and displaced persons, old and disabled people. Since children are still maturing physically and mentally and are more dependent on care provided by others, they are particularly vulnerable. Covid-19 has more rarely severely affected children and youths. According to the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (Unicef), 17,200 children and young people under the age of 20 years world-wide died from a Covid-19 infection. This represents 0.4 per cent of corona mortalities of a total 4.4 million people. However, the social and economic effects of the pandemic hit children harder than adults; by now, nearly all indicators referring to the situation of children are showing a dramatic worsening:

- Already before the pandemic, children – understood here as all people under the age of 18 years – had been disproportionately highly affected by poverty: children account for a third of the world population, but more than half of the extremely poor, those having to live on less than 1.90 US dollars a day. As a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, the number of children in extreme poverty has risen by around 150 million to 725 million girls and boys.

- Together with economic anxieties and isolation in lockdowns and quarantine, stress in families increased, too. In all countries throughout the world, domestic violence against women and children rose. Help was hardly available, for the advice and shelter facilities were closed.

- Public healthcare, already insufficient, especially in rural areas, was no longer accessible for many people. This had dramatic and long-term consequences. Pregnant women and infants were not cared for, while vaccination campaigns against polio or measles were suspended.

- During the peak of the lockdowns, in 2020, according to Unesco, 1.5 billion children were unable to attend school. Around 463 million of them could not make use of digital learning services. For 365 million schoolchildren, school closures also meant the suspension of free school meals, often enough the day’s only nourishing meal.

Families in need resort to coping strategies at the expense of their children, who then have to join in working. Girls are married earlier, with hopes that their husband’s family will care for them better.

- In June 2020, the International Labour Organization (ILO) noted that after two decades of progress and declining numbers of children in labour, significantly more children were having to work. The increase in wars and conflicts and the impact of the corona pandemic are responsible for this. Now there are studies on the situation in Ghana, Uganda, Nepal, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India and Myanmar, which show that during the lockdowns, significantly more children were working, many of whom did not return to school. Girls and boys who had already contributed to family income before the pandemic have frequently slipped down further into even poorer working conditions. For example, they have to work longer or harder, as the Child Labour Report 2022 demonstrates. More children are working in bonded labour and in slavery or in prostitution. Already in the early stages of the pandemic in May 2020, terre des hommes partner organisations from the Philippines reported that the demand for young girls for webcam child prostitution was on the increase. At the same time, Europol stated that the demand for child pornography in the Internet had strongly increased since the beginning of the lockdowns.

- Unicef estimates that the number of girls forcibly married before their 18th birthday has risen by 10 million to a total 100 million child brides owing to the corona pandemic.

… and what we don’t know

However, just how and to what extent the pandemic is impacting on children can only be partly demonstrated, for the data base is poor. One of the reasons for this is that gathering data depends on having the necessary means and knowhow, which are often lacking. But another reason is that children are not at the focus of interest in society and politics. This applies in particular to children in poor families and from marginalised and discriminated groups, in rural regions, and in war and crisis areas, as well as to refugee and displaced children. Furthermore, children are often left out in data collection – not only when statistics are not broken down into age groups, but also because interviews often follow a fixed pattern. Heads of families are interviewed – often the men, while the children’s perspective is not revealed. For example, owing to a lack of data, it is not clear whether and how the collapse of health systems due to the pandemic is affecting child mortality (mortality of newly born and under-five-year-olds). According to Unicef, two thirds of the developing countries and emerging economies cannot provide reliable data on child mortality.

The middle- and long-term consequences of the pandemic are only going to become apparent over the next few years. For example, how will undernourishment during the lockdowns take effect? Hunger and malnutrition of women during pregnancy, of babies and infants, often damage children’s entire lives, for they impair brain growth and lead to delayed development and stunting.

Will children who have experienced falling into poverty or violence, or lost parents or relatives in the pandemic, be capable of creatively and self-consciously developing their lives in difficult circumstances? How is lagging behind in education going to impact children? Will there be an increase in mental diseases? How many families have run into debt to pay doctors’ bills and medicine? Who is going to work off debts in times in which there are huge food price hikes owing to failed harvests, following flooding or droughts and the consequences of the war against Ukraine?

Poverty, conflict, pandemic – the example of Iraq

Zainab is twelve years old and lives together with her sisters and grandmother in Ramadi, about 110 kilometres west of Baghdad. She lost both her parents in the armed conflicts over the last few years. When the school was closed because of the corona lockdown, Zainab lost her one and only opportunity to leave the house. She became depressed and started to inflict injuries on herself.

Lasting 63 weeks, the school closures initiated by the Iraqi government and the Kurdistan-Iraq regional government were among the longest in the world and affected eleven million children. Re-openings of schools were not uniform and were interrupted several times. Around 7.4 million children were unable to attend digital education services because they had neither smartphones nor computers nor Internet access. Before the pandemic, every fifth child in Iraq had been living in poverty. With the lockdowns, unemployment continued to rise in an already fragile economy. Today, 40 per cent of the children in Iraq are living in poverty. Domestic violence has increased strongly, as have negative coping strategies: dropping out of school, child marriages, child labour. According to the UNHCR, refugee and displaced children are especially hard hit.

Placing children at the centre of policies

Cute from Zimbabwe calls for free-of-charge and good-quality education for all children, secure employment for adults and better drinking water supply. Her demands can only be fulfilled if politics and the economy are fundamentally reoriented. The international community urgently has to invest more in areas which are particularly important for children and can strongly improve their situation: food security, healthcare, clean drinking water, education and protection from violence and exploitation. The development of social security systems is crucial to making families more resilient towards crises.

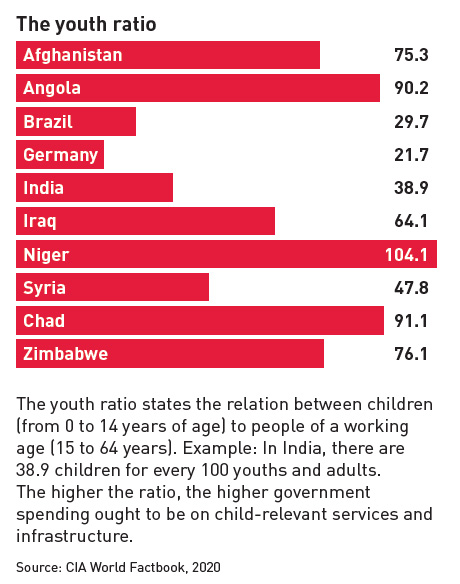

Children and youths account for 30 per cent of the world population, while 2.35 billion people are younger than 18 years. In many developing countries and emerging economies, children form the largest population groups. The international community has often promised significant improvements for children. It is high time to listen to children, involve them in decisions and put their interests centre stage.

Where children’s rights are enshrined

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) was adopted in 1989 and ratified by all the world’s nations with the exception of the USA. The Convention

defines a child’s rights to protection, support and participation. Supplementary conventions stipulate the rights of children in armed conflicts and protection against child trafficking and sexual exploitation as well as an individual complaints procedure. At regular intervals, the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child reviews how governments comply with the Convention and presents recommendations. The protection of children against exploitation is defined in ILO Convention 182 on the “Worst Forms of Child Labour” for the ILO member states.

Barbara Küppers is a sociologist and journalist, and she works as Public Affairs Manager for the child relief organisation terre des hommes. The organisation is based in Osnabrück, Germany and supports projects for children in 43 countries. Contact: b.kueppers@tdh.de

References

World Development Report 2022

WDR 2022 Chapter 1. Introduction (worldbank.org)

World Social Protection Report, 2020–22, ILO, Geneva 2022

www.data.unicef.org/topic/child-survival/covid-19

Child Labour Report 2022

Child Labour Report 2022 – Building Back Better after COVID-19 – together with children as protagonists (tdh.de)

Europol. How criminals exploit the COVID-19 crisis, March 2020: 4

COVID-19: A threat to progress against child marriage - UNICEF DATA