Healthy diets – a privilege of the rich?

Deficiencies in iron, zinc, vitamin A and other micronutrients can have serious negative health consequences for both children and adults. It is estimated that more than two billion people world-wide suffer from micronutrient deficiencies – a condition also known as hidden hunger because even mild or moderate deficiencies that do not show visible symptoms can be harmful. The risks of hidden hunger are elevated for young children and pregnant women for whom micronutrient needs are relatively higher. The 2008 Lancet report estimated that more than one million children die every year because of micronutrient deficiencies. The best antidote against hidden hunger is a diverse diet rich in fruits, vegetables, pulses and animal-source foods (meat, poultry, fish, eggs and dairy).

What defines a healthy and diverse diet?

But can everyone afford a healthy and diverse diet? Studying this question is made difficult by the fact that there is no universal agreement on what defines a healthy and diverse diet. Earlier research in this area focused on high-income countries and often equated a healthy diet with the one consumed in the Mediterranean region, motivated by the finding that average life-expectancies are higher in that region than elsewhere. Another branch of this work defined healthy diets using national food-based dietary guidelines that provide recommended intakes from different food groups taking into account local dietary habits and food availability. Unfortunately, neither of these approaches is well suited to study this question in many low- and middle-income countries, where the bulk of the world's poor people reside. First, the Mediterranean diet does not align with the dietary habits and preferences in Africa, Asia or Latin America. Second, only a handful of countries in these regions have developed their own national food-based dietary guidelines.

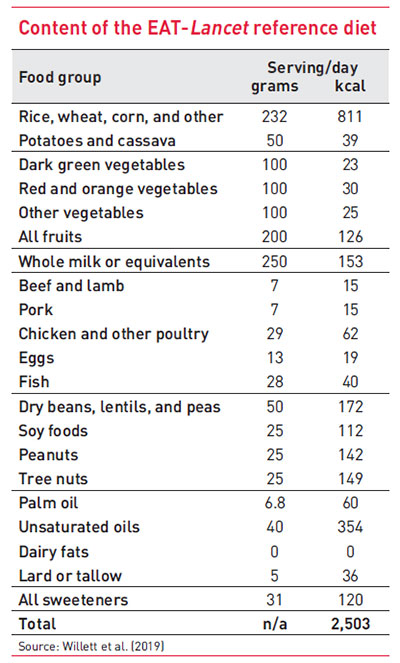

An important development in this regard was the formulation of the planetary healthy diet by the EAT-Lancet Commission in early 2019. The Commission was tasked to define a set of diets that limit diet-related disease risks and minimise the environmental harm caused by our food choices. The outcome was a proposition for the world’s first global reference diet that is reasonably flexible to accommodate most dietary traditions around the globe. The Table shows the Commission’s recommended ranges of intake for the major food groups considered for an adult consuming 2,503 calories/day. Like most national dietary guidelines, the Commission proposed consuming a diverse range of fresh or lightly processed foods while limiting the intake of red meats, sugary products, and saturated fats and oils.

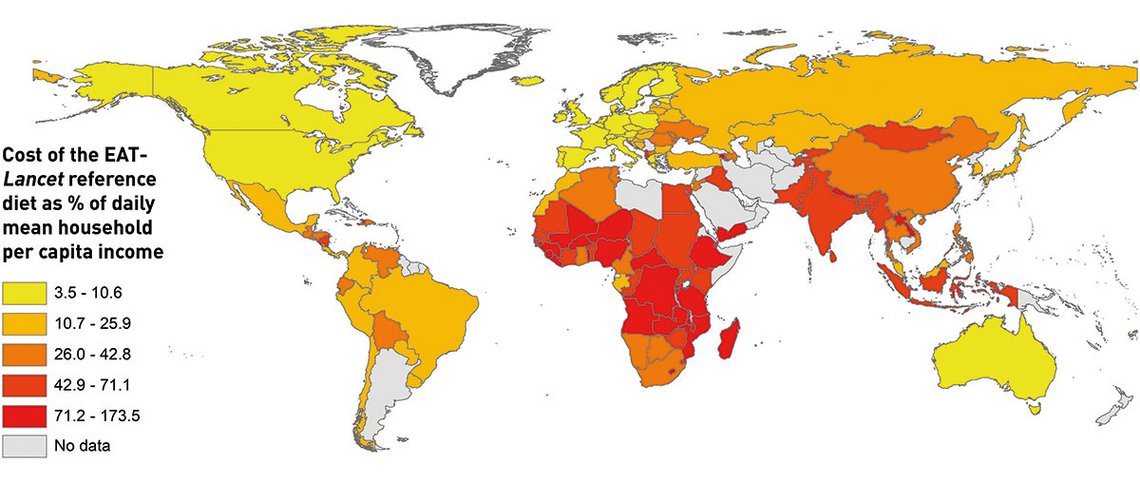

While many experts continue to debate the scientific merits of the EAT-Lancet diet, the reference diet opened up new options for exploring the affordability question. In a recent study published in the Lancet Global Health, we calculated the cheapest means of meeting the EAT-Lancet dietary intake recommendations in the reference diet in 159 countries, together representing 95 per cent of the world’s population. Using standardised retail price data collected under the International Comparison Program, we worked out that for the median country, the cost of the EAT-Lancet reference diet was 2.89 international dollars based on 2011 purchasing power parity exchange rates. This may not sound a lot, but it exceeds the dollar 1.90 international poverty line set by the World Bank by more than 50 per cent. The true cost is likely to be higher because these estimates do not include costs associated with acquiring and preparing the food – household activities that often fall onto women. Comparing the estimated daily costs against available incomes, we calculate that nearly 1.6 billion people around the world cannot afford such a diet (see Figure). In sub-Saharan Africa and South-Asia, the two regions hosting the most of the world’s poor and malnourished people, the estimated cost exceeded the available incomes for 57 per cent and 38 per cent of the population, respectively.

Making healthy food affordable is not enough

Our research suggests that the world’s poor cannot afford a healthy and diverse diet – a finding that has been confirmed by a number of recent country-specific studies from Africa and Asia. So what can be done? First, the large observed disparities in affordability are mostly driven by the highly unequal global distribution of income. Thus, raising the incomes of the poor is a necessary condition for improving diets. Targeted income transfers in the form of cash, food or vouchers can improve diets in resource-poor settings if coupled with effective nutrition communication strategies that nudge households to allocate more of their food budget on nutrition-rich food items. A longer-run strategy involves investments in sectors of the economy that promote job creation and inclusive income growth.

Second, there is also scope to reduce the prices of nutrition-rich foods. Fresh fruits, many vegetables and healthy animal-sourced foods like milk, eggs and fish are often very expensive, especially when compared to calorie-rich but micronutrient-poor grains and tubers. In poor countries, the high cost of these nutrition-rich food stems from low farm-level productivity as well as inefficiencies in the post-harvest stage (storage, transport, and processing). There is also scope for designing nutrition-smart fiscal policies that favour healthy foods and tax unhealthy foods.

Finally, making healthy foods affordable is unlikely to be sufficient. Growing numbers of people in middle- and high-income countries consume excessive amounts of refined carbohydrates, saturated fats, sugar and salt – ingredients that elevate the risk of obesity, cardiovascular diseases and various types of cancer. Worryingly, we start to see similar unhealthy dietary patterns emerging among affluent consumers residing in low-income countries. This calls for more investments in nutrition education and more stringent regulation in food marketing so as to make consumers more aware of the health implications of their dietary choices.

A world free of hidden hunger can be achieved, but it requires global commitment – and a lot of work.

Kalle Hirvonen is a Senior Research Fellow at the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), based in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. This article was based on research done together with Yan Bai (Tufts University/USA), Derek Headey (IFPRI) and William A. Masters (Tufts University).

Contact: k.hirvonen@cgiar.org

References:

Black, RE, LH Allen, ZA Bhutta, LE Caulfield, M de Onis, M Ezzati, C Mathers, and J Rivera. 2008. "Maternal and Child Undernutrition Study Group: Maternal and child undernutrition 1-maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences." The Lancet 371:243-260.

Hirvonen, Kalle, Yan Bai, Derek Headey, and William A Masters. 2020. "Affordability of the EAT–Lancet reference diet: a global analysis." The Lancet Global Health 8 (1):e59-e66.

Rao, Mayuree, Ashkan Afshin, Gitanjali Singh, and Dariush Mozaffarian. 2013. "Do healthier foods and diet patterns cost more than less healthy options? A systematic review and meta-analysis." BMJ open 3 (12):e004277.

von Grebmer, Klaus, Amy Saltzman, Ekin Birol, Doris Wiesman, Nilam Prasai, Sandra Yin, Yisehac Yohannes, Purnima Menon, Jennifer Thompson, and Andrea Sonntag. 2014. "2014 Global Hunger Index: The challenge of hidden hunger." IFPRI books.

Willett, Walter, Johan Rockström, Brent Loken, Marco Springmann, Tim Lang, Sonja Vermeulen, Tara Garnett, David Tilman, Fabrice DeClerck, Amanda Wood, Malin Jonell, Michael Clark, Line J Gordon, Jessica Fanzo, Corinna Hawkes, Rami Zurayk, Juan A Rivera, Wim De Vries, Lindiwe Majele Sibanda, Ashkan Afshin, Abhishek Chaudhary, Mario Herrero, Rina Agustina, Francesco Branca, Anna Lartey, Shenggen Fan, Beatrice Crona, Elizabeth Fox, Victoria Bignet, Max Troell, Therese Lindahl, Sudhvir Singh, Sarah E Cornell, K Srinath Reddy, Sunita Narain, Sania Nishtar, and Christopher J L Murray. 2019. "Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems." The Lancet Published Online January 16, 2019. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31788-4:1-47.

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment