Creating livelihoods through clean energy and agriculture

With the economic impacts of the current pandemic projected to be of historic proportions, the future of work is a source of major uncertainty, particularly in emerging economies. After two decades of per capita income growth rates that outpaced those of rich countries, economic activity in sub-Saharan Africa has decelerated, driven by factors involving external developments, difficult domestic conditions and low commodity prices. Economic growth was down to 2.3 per cent in 2018, severely impacting the availability of jobs. The growing impact of climate change on Africa’s largely rain-fed agricultural sector compounds these issues, deepens the food crisis, and also affects the predictability and availability of work for millions in farming, which employs over 65 per cent of the continent’s labour force. Increased automation and mechanisation will improve yields and reduce farm costs but may jeopardise traditional agricultural job opportunities.

Meanwhile, as jobs grow scarce, recent improvements in healthcare access, among other factors, have led to a youth explosion. As of 2018, the rate of population growth has exceeded the rate of economic growth for four consecutive years, and according to the African Development Bank, young men and women between the ages of 15 and 24 years comprise over 34 per cent in sub-Saharan Africa today. The World Bank estimates that each year, ten million young Africans join the ranks of those looking for work. So, there is an urgent need to regain momentum on sustained growth. Virtually of all the various “big push” agendas, from the Africa Union to national development strategies, list energy and infrastructure development among the top priorities for Africa.

Renewables at the core of Africa’s energy transition

The challenges of energy infrastructure include a lack of adequate transmission networks to support the distribution of power resulting in grid congestion, system inefficiencies and high losses, utility mismanagement, the difficulty of cost recovery as usage rates remain low across the continent, and more. Another major challenge lies in the difficulty of delivering electricity to remote and rural communities. In fact, access to electricity stands at 35 per cent of the population, with rural access rates at less than one-third of urban communities. The United Nations estimates that globally, 650 million people will still lack access to electricity in 2030 and nine out of ten of them will be in sub-Saharan Africa. Many African countries are in the midst of an energy transition as utility-scale solar, wind and geothermal power projects displace diesel generation, battery storage systems make headway and rural electrification receives growing attention.

Renewable and decentralised technologies are at the centre of this energy transition. Eastern African countries alone have announced more than 2,000 MW in new solar photovoltaics (PV) and wind power projects coming online in the next three years. In fact, more than 40 per cent of sub-Saharan Africa countries have official rural electrification targets, and at least a third have specific decentralised renewable energy targets or plans. From January to June 2019, over four million quality-certified solar lanterns, multi-light and solar home systems were sold on the continent. And while there are only 1,500 mini-grids currently installed, another 4,000 mini-grids (mostly third generation solar-hybrids) are in various stages of planning and development across Africa.

Quantifying jobs in the clean energy sector

There may be a major opportunity for employment through delivering energy services to the 650 million people who still lack access. Decentralised renewable energy technologies – which enable power generation to happen close to the node of consumption – are agile, able to reach remote communities or “the last mile” more efficiently and are growing their market share quickly, already helping to stimulate productivity. In fact, agriculture, the sector which still dominates the African economy, is likely the sector best poised to benefit from the potential of clean energy access to mitigate climate change, unlock productivity, and thereby boost near-term economic growth and, of course, create local jobs. So, food security, livelihoods, energy access and advances in renewable technologies are inherently connected. The question is: how can we unlock the potential of this interconnectivity?

Part of the challenge is the lack of data for informed, sharp, targeted policy intervention. There are few studies to date that provide reliable job counts for the renewable energy sector in Africa, and there is little quantitative data on the specific skills gaps that hinder the sector’s growth. Filling the data gap needed to inform policy is the goal of the #PoweringJobs campaign, founded by a coalition of partners, led by the international non-profit organisation Power for All. Recently, the campaign launched a job census – the first of its kind, bottom-up count of employment in decentralised renewable energy in sub-Saharan Africa. It focuses on Nigeria and Kenya – one of the fastest growing and one of the most mature renewable energy markets, respectively.

Released in 2019 this is the most comprehensive job survey known to date, but only scratches the surface of job estimation, creating a baseline for future data collection exercises. The survey captures employment data for over one hundred companies in Nigeria and Kenya which are engaged in renewable energy products and services, from those selling solar lanterns, solar home systems and solar irrigation systems to commercial and industrial stand-alone solar systems and renewable energy powered mini-grids. This means the sample covers decentralised renewable energy companies working in off-grid, weak-grid or on-grid communities across the local supply chain, from manufacturing and wholesale imports to sales, installation and operations.

Enabling job creation through productivity

The early data shows that the renewable energy sector has emerged as a significant employer in emerging markets. Although nascent and just beginning to scale, decentralised renewables have already grown a direct workforce comparative to traditional utility-scale power sectors. In Kenya, the sector employs around 10,000 people in direct, formal jobs, almost as many as the national utility company in Kenya according to its own estimates. Decentralised renewable energy companies in Nigeria employ about 4,000 people in direct, formal jobs, the same order of magnitude as those in the electricity, gas and steam sector in Nigeria. Importantly though, compared to this formal job impact, decentralised renewables engage twice as many workers through informal jobs. This is critical as informal work is the largest source of employment for most sub-Saharan Africa.

Moreover, applying best estimates from the literature suggests as many as five times the number of persons may be gaining employment through jobs stimulated by newly powered productivity, enterprise and business in rural areas. While salons, food, retail and entertainment kiosks are popular, a new wave of agriculture-processing enterprises is emerging – from fruit drying to refrigeration and cold storage, milling, egg incubation, honey processing and more. There are over 100 firms developing off-grid solar productive use appliances for the African market and hundreds more distributing them. Sales are still relatively low since many agro-processing units are as yet in pilot stage, but this is anticipated to be a major new sector in the coming years.

This is important because women and youth are the hardest impacted by the dearth of rural employment opportunities, due to lack of education, traditional perceptions of gender roles, lack of social mobility and a host of other sociocultural factors. To give a sense of scale, rough estimates of ‘productive use jobs’ stimulated through new or improved electricity access were 65,000 in Kenya and 15,000 in Nigeria at the time of study. But because energy companies do not standardly track end-user job creation as a performance metric, they cannot place strong confidence in their estimates. And as mentioned, the literature is thin, requiring more research.

Exactly what types of jobs are renewable energy creating in Nigeria and Kenya? Companies employ electrical engineers, programmers, technicians, technology designers, metering experts, data analysts/data managers, software engineers and monitoring experts. Finance, legal and business managers, as well as sales, retail, product distribution, logistics managers, customer care and customer engagement agents are also all core to business function. There are of course further jobs in upstream industries (like local solar panel manufacturing) and downstream industries (such as waste recycling).

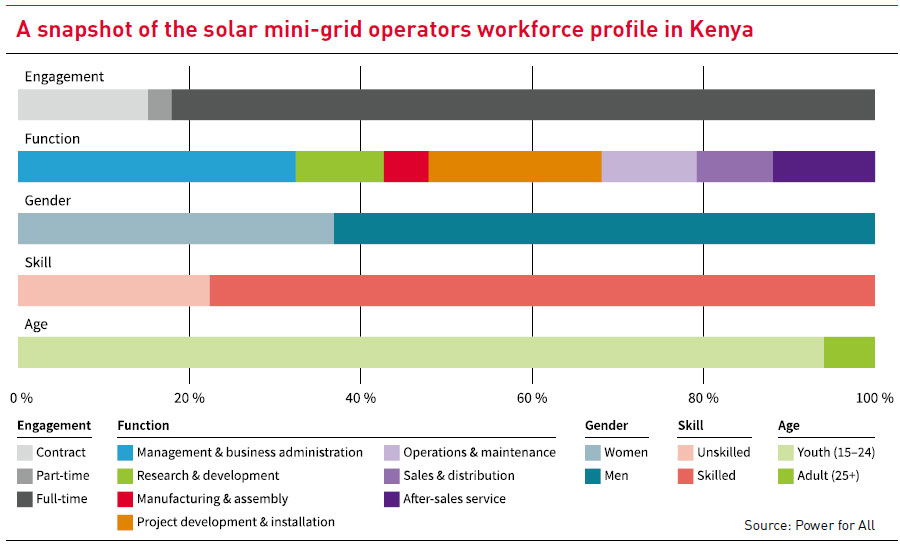

For each type of technology, the value chains and thus the required job functions vary. Solar mini-grid companies, for instance, are seeing need for micro-financers, community trainers and entrepreneur support service professionals, to support the businesses and enterprises developing through access. These types of customers are important to revenues, so mini-grid companies expect this aspect to become more core to their business model over the near future. Over two-thirds of the decentralised renewable energy workforce is skilled and full-time, with average retention being more than 30 months and average compensation falling within the middle-income range of both countries.

Filling the skills gaps is crucial

Pairing these findings with publicly available future market projections suggests that many, many more jobs may be possible, but decentralised energy companies say they are challenged by skills gaps, and by recruitment barriers. In fact, it is said that human resource, not technology, is what makes or breaks companies in this field. While technical (STEM) training is key, companies revealed having the most difficulty in recruiting for management, finance, legal, sales and marketing skills. But entry-level graduates from these programmes are often in short supply, and established recruitment channels to reach them are frequently just simply missing.

These challenges, compounded by other social barriers and business cultures, leave women’s representation lacking. On average for Kenya and Nigeria, women make up less than a third of direct, formal workforce and fill about 25 per cent of managerial roles. But women are critical to the sector’s ability to expand access. For instance, women, as the social influencers within their communities, play a major role in successful sales, product distribution and micro-enterprise development. Alongside technical skills, companies explained that recruits were often not industry-ready, in terms of lacking general business soft skills, like communication, leadership and critical thinking. Soft skills are important to every job function across the board for strong business performance. This applies especially to younger, entry-level recruits. Although young people make up 40 per cent of the sector’s workforce in Kenya and 30 per cent in Nigeria, companies agreed that there was opportunity to hire even more.

Strategies to unlock the renewable energy job creation opportunity

This kind of data provides many insights for interventions that can help increase job creation in the near term. There are clear skills needed to both expand renewable energy at scale and create more employment. First, stronger collaboration is needed to develop standardised, accredited, industry-relevant training programmes and career development programmes for graduates. Second, establishing formal recruitment pipelines for youth and women is an overlooked area where vocational training, higher education institutes and industry associations can play a pivotal role. Third, the sector’s massive footprint in the informal and productive use job creation presents an opportunity to directly support new innovations in agricultural processing, while also encouraging direct training interventions, and the formalisation of labour to align with local and international decent work standards, compensation standards, and social protection. Finally, all these early indicators suggest that much more quantitative research is needed to understand job displacements in other sectors, indirect and induced job impacts, and productivity, requiring more cross-sector data, and standard reporting metrics and sampling tools directed toward end users, with a focus on different productive use value chains. Delivering affordable, reliable energy access quickly through renewable energy solutions that meet people where they are is a major way to open economies, especially in rural areas. Particularly in these times where identifying ways to jumpstart economic recovery and build resilient systems is key, renewables should be core.

Rebekah Shirley is the Chief of Research at Power for All, an international non-profit organisation promoting integrated approaches to universal electrification. Rebekah and her research team have won many awards for thought leadership in the African energy sector. Before living in Kenya, Rebekah was a Chancellor's Fellow at the University of California, Berkeley, where she earned her PhD researching solutions for power systems optimisation in emerging markets.

Contact: rebekah@powerforall.org