- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Making markets work for the poor II – Enhancing sustainable income for vulnerable farmers in the Philippines

Eastern Samar, a province in Region VIII of Eastern Visayas of the Philippines with a population of 470,000, was struck by Super Typhoon Haiyan, locally known as Yolanda, on the 8th November 2013. It was the strongest storm to ever make a landfall in the Philippines in recent history, leaving 6,201 dead, 1,785 missing and 28,626 injured. The agriculture sector sustained damage around 31 billion PHP, the equivalent of total agricultural output generated in two years. More than 33 million coconut trees were damaged or destroyed, jeopardising the livelihoods of more than one million farming households. Coconut palms require an average of six to ten years to produce the first fruit but can take 15 to 20 years to reach peak production.

Large sections of the Eastern Samar population are in a vicious circle of poverty and inequality that was further exacerbated by a series of natural disasters, mainly typhoons. Poverty incidence in the region was one of the highest in the country even before Typhoon Haiyan. In the first half of 2015, it was at 50 per cent. Most of the poor live in rural areas and work in the agricultural sector, chiefly in farming and fishing.

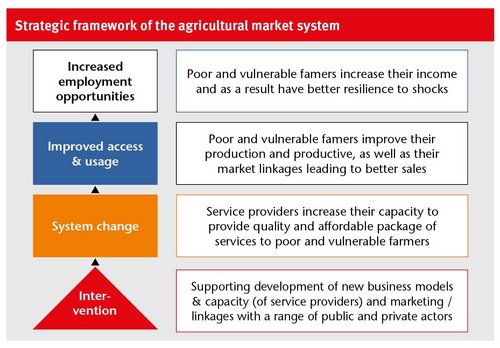

Against the above backdrop, a consortium of HELVETAS Swiss Intercooperation (as the lead agency), People in Need (PIN) and Agency for Technical Cooperation and Development (ACTED) implemented phase I of a Recovering and Rehabilitating Livelihoods project. While contributing to immediate recovery and rehabilitation of poor and vulnerable women and men farmers in Eastern Samar, phase I of the project (2015-2016) aimed at a long-term improvement of their livelihoods. The project applies the market systems development (MSD) approach. This article presents the experiences of the project in supporting the generation of sustainable income, focusing on understanding the root causes of poverty and vulnerability in the agricultural system and engaging in and working with a range of stakeholders.

Step I: Understanding the agricultural system

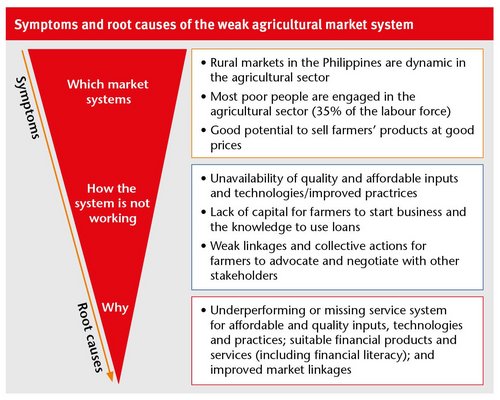

The assessment of the agricultural system at the beginning of the project found the following constraints:

Lack of access to and limited knowledge of affordable and quality inputs, services and technologies/practices. This problem was worsened by the disruption of markets after Haiyan had hit. Even if farmers did have access, there was a problem of inappropriate usage of inputs or unsuitable practices that contributed to the deterioration of soil fertility, leading to higher production costs and reduced productivity and income.

Absence of suitable financial services and products and low financial literacy. This prevented farmers from starting and expanding their business through investments. Most agricultural products are seasonal, so that income for loan repayment is generated over the long term. Risk and uncertainty often exist in the agricultural sector, including the vagaries of weather and market shocks. Farmers interviewed in the province did not regard the availability of micro-finance institutions (MFIs) or banks as the major problem. Yet only 29 per cent of them took loans before the typhoon, and a mere 19 per cent did so after the typhoon. Furthermore, lacking financial literacy skills, farmers tended to react to immediate problems and needs and had little time to consider options, trade-offs and longer-term consequences of over-indebtedness and erosion of assets.

Weak market linkages with a range of actors: Production was on a small scale and did not attract bigger market players owing to weak market linkages that undermined farmers’ incentives to diversify and invest. They had no access to information about price, supply and demand, and quality of products/inputs. Above all, even if market information was readily available, it required analysing and making good decision. Usually, farmers knew little about the agricultural markets outside their local area and sold their produce to their neighbours at a low price. They were generally not aware of intended end-market or retail prices.

The root cause of the above problems was an underperforming or missing service system for affordable and quality inputs, technologies and practices, suitable financial products and services (including financial literacy), and improved market linkages. Services were constrained by a lack of quality providers, with assets including market awareness, sustainable business models and marketing strategies. These services would increase awareness of the benefits of diversifying the agricultural products of farmers beyond relying on what was left of coconut production.

Step II: Promote service provision

The focus of the project was to support farmers’ livelihood diversification or shift from coconut production to other sources such as crops, commodities and livestock. The key to this was the availability and quality of service packages (input, consulting and marketing) to farmers, which the project supported based on the analysis of the agricultural sector. The main constraints to be tackled were:

- awareness of service providers on marketing the potential service to users (farmers) and the profitability of the package of services, for example, by engaging more private enterprises such as input producers, banks and MFIs,

- service providers’ capacities, in particular local service providers (LSPs), who are closer to the farmers and live within the communities, and

- development of quality and affordable package of services.

However, given both dependency on the influx of free handouts by many non-governmental and other organisations and the lack of resources, many in the province believed that poor and vulnerable farmers would never buy services.

Identification of service providers.Community meetings were organised to explain the LSP concept and process. Candidates for LSPs had to fulfil some key criteria (such as being a resident and respected member of the community, having at least completed high school, having good business and communication skills). These criteria were published in the Barangay halls, the lowest administrative unit, for a period of three weeks, making sure that all interested people would have a chance to apply. To facilitate the identification and selection of LSPs, the project supported the organisation of LSP Selection Committees, consisting of representatives of farmers, Barangay officials, women’s association and neighbouring communities with a minimum of seven members.

Raising awareness on the profitability of providing a package of services. This was done by holding a series of workshops with potential providers and farmers. The latter were targeted directly in their respective location by the project team and the LSPs themselves. In addition, visually attractive leaflets were printed out and distributed, and local radio stations were approached to disseminate information about LSP services. This was also aimed at informing and engaging other stakeholders such as private enterprises and government agencies like the Department of Agriculture and local government units about the potential of these new or improved service packages and at working with and supporting service providers.

The results

The project facilitated the designing and provision of suitable financial products and services and created better financial literacy of farmers in terms of choice of products, borrowing, investment, savings and insurance. Also, it has improved farmers’ access to markets. All this has laid the foundation for a recovery of the area and long-term income of poor and vulnerable farmers.

More than 2,000 farmers from 70 Barangays and 30 farmers’ groups have used and increased their technical, business and financial capacities. According to the project’s monitoring system, 80 per cent of the 2,000 farmers benefiting from capacity building increased their income by over 70 per cent over the past six months. In total, services were provided to 5,000 farmers from 128 Barangays, as well as 3,000 non-targeted farmers in 58 Barangays.

Service providers consolidated around 80,000 kilos of vegetables worth 3.2 million PHP (1 USD = 47.45 Philippine Peso) . The project has also facilitated signing of 14 contracts and generated more than 1,000 of purchase orders from over 400 regular buyers of farm products as of July 2016. Together with the financial service providers and LSPs, financial agencies (e.g. micro-financial institutions), provided financial literacy training to the farmers. Through the LSPs, the project enrolled around 1,100 farmers in the free crop insurance programme of the Philippine Crop Insurance Corporation (PCIC), covering more than 18,000,000 PHP.

The project is the only initiative in the area that seeks to contribute to long-term development by tackling root causes of underperformance in the agriculture system. However, working in an environment where the majority of the organisations have implemented cash-based projects has been a challenge for the project. Cash-based supports offering more and quicker benefits are more attractive for the farmers than participating in the trainings or other activities with longer benefits.

Key lessons for implementing MSD projects

Gaining a better understanding of the market system

The market assessment conducted by the project was crucial to identifying the root causes of the underperformance or failure of the different systems around agriculture. This also includes a clear definition of poor women and men, and systematically ensuring that they are at the centre of the interventions. In some sub-sectors, the project benefited by obtaining relevant information regarding opportunities and constraints of the market systems, which guided its actions through constant feedback and adaptation.

Having a clear vision from the start

Given the fragile context in which the market system was underperforming, financial and other inputs (e.g. training) from the project were required to kick-start the process. However, this needed to be translated into specific plans for scaling down the inputs of the project to ensure that the actors engaged initially (e.g. LSPs, MFIs) would own the improved systems and the others would copy and scale up the initiatives. In this connection, the sustainability matrix, i.e. “who does/who will do; who pays/who will pay” is the key to measure the sustainability and scalability of the impacts.

Facilitating an accessible and inclusive service provision system

The LSP system was found to be very effective in creating farmers’ access to inputs, services, technologies and markets. Nevertheless, selection of LSPs through a proper process with the right criteria (e.g. interest, prior experience, being from the community etc.) ensured the expected level of commitment of the LSPs to develop their skills and continue their profession as LSPs well beyond the project’s lifespan. Persons having the required level of qualifications and competencies are also in very high demand in local job markets. So support of the project (including financial) is needed to attract skilled individuals to work as professional LSP. However, this support of the project needs to be gradually reduced as earning from service selling increases.

Adaptive management in a fragile context

Systemic change (e.g. improved package of services leading to large-scale and durable impacts) takes time to show compared to direct delivery, particularly in a post-disaster context that has also been perennially poor and naturally exposed to risks because of its location. Therefore, a well-defined monitoring and evaluation (M&E) system and adaptive management has been crucial to understand what contributes to making meaningful and measurable impacts for poor and vulnerable women and men farmers.

Zenebe Uraguchi

HELVETAS Swiss Intercooperation

Bern, Switzerland

Zenebe.Uraguchi@helvetas.org

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment