Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Making markets work for the poor – an example from Bangladesh

The agricultural sector is one of the single largest sectors of the Bangladesh economy and supports more than 75 per cent of the population with direct and indirect sources of livelihoods. The rural markets are dynamic both in agricultural and non-agricultural products. For poor and very poor producers, good potential exists to sell their products on local, regional and national markets. However, access to markets beyond these levels, with better prices, is challenging for them owing to low product quality, less market information, weak organisation of producers, limited marketable surplus, etc. The producers are trapped by these constraints and sell their products more often to middlemen, at the farm gate and with less competitive prices.

To address market failures affecting poor and very poor farmers, Helvetas Swiss Intercooperation launched the Swiss government funded Samriddhi project (Samriddhi in Bengali means ‘prosperity’) in the Northwest and Northeast of Bangladesh in August 2010. The goal of the project, which ended in February 2015, was to contribute to sustainable well-being and resilience of poor and very poor households through economic empowerment. The project was designed with the impact logic that (i) if public and private services for business development are available and poor people are empowered and capacitated to access these services, and (ii) if an enabling environment for pro-poor economic growth exists, poor people can generate additional income and overcome their poverty situation in a sustainable manner. This project addressed about 5,700 farming communities (farmers’ groups), including around 320,000 farmers/producers who were directly addressed and a further 580,000 farmers and producers who were reached via the Local Service Providers/market actors (who were supported/facilitated by the project).

How the M4P approach works

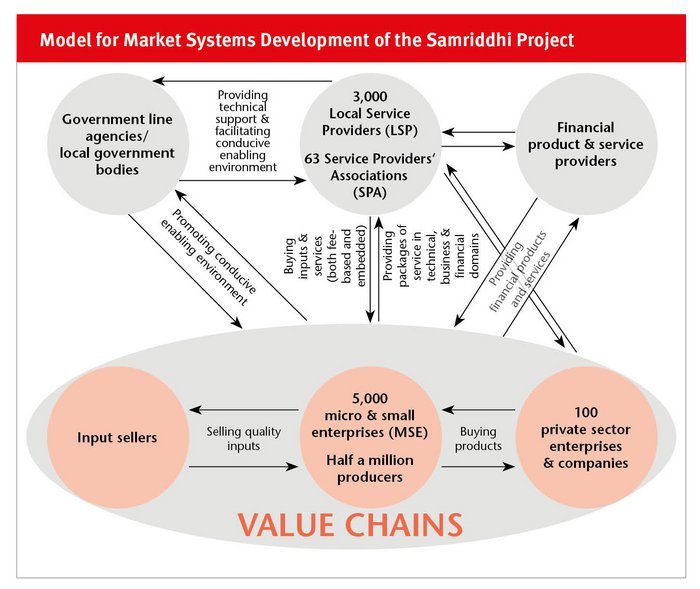

Samriddhi followed the Making Markets Work for the Poor (M4P) approach, which identifies systemic constraints and root causes of market failures and addresses them by aligning incentives and capacities of market actors. Here, the project focused on upgrading twelve agricultural value chains to support the economic empowerment and development of the poor and very poor as entrepreneurs and enhance their skills. The twelve selected value chains/products were: vegetables, fruits, medicinal plants, dairy milk, beef (bull fattening), goat, duck, chicken, fish, cotton craft (including mini garments and hand embroidery), jute crafts (products by jute fibre) and plant craft. The process started with understanding the market systems in which poor producers operate. The project worked with public and private actors (see Figure), and in particular with private sector enterprises, as important players to influence and change the market systems.

Public extension services and market actors were incentivised to engage with local service providers (LSPs), local traders and input and output market service providers with the aim to reduce the high transaction costs of reaching millions of producers. In this model (see Figure), LSPs offer producers a holistic package of embedded services ranging from business planning through technical advice (production technology) and market linkage (access to input and output market) to the facilitation of access to financial services. LSPs charge fees for their services and are entrepreneurial lead-farmers who act as a hinge between producers, local agribusiness enterprises, private companies, and public service agents. They are often organised in service provider associations (SPAs).

Large national agribusiness firms dealing in input and output as well as small enterprises and traders in the local markets buying and selling products and inputs, are a source of finance, both in kind and cash, and together with the government line agencies, they contribute to the capacity building of the LSPs and their SPAs for the delivery of affordable, accessible and quality services.

Producer groups are organised in informal micro and small enterprises (MSE) and connected in MSE networks that are integrated in the different value chains. MSEs are business entities comprising groups of 15 to 20 farmer entrepreneurs and labourers who invest and are involved in production and marketing. LSP support is aimed at changes in the attitudes towards collective action and enhances the capacity of the MSE (networks) in technical knowhow, business management and acquisition of financial capital.

How the market system improved

The targeted rural marked systems changed in many ways. Through the prospect of increasing outreach or area coverage, product penetration and/or market share and reduce transaction cost, the project incentivised more than 100 private companies, local entrepreneurs and relevant public sector entities to build LSP/SPA’s capacity, thus empowering poor and very poor producers through their deeper integration in the relevant input and output markets. For example, in the vegetable value chain, poor and very poor producers had less access to quality inputs (seed, fertiliser etc.), as each producer required a small amount of inputs as well as money to cover procuring the inputs from far off. LSPs organised the producers, established input demand among producer groups and made the required inputs available at a fair price at their doorstep. This process reduced transaction costs of both producers and input sellers. LSPs also facilitated producer groups and traders to establish and run a collection centre in the closer proximity of farmers’ villages. In the collection centre, the farmers sell their produce at a price similar to that on the distant markets. Here, the incentive for the traders was that they could buy bulk volume in one place according to market demand. On the other hand, the farmers could sell their product at a competitive price. This approach also supported farmers in reducing their post-harvest loss. Moreover, the collection centre approach reduced transaction costs of both producers and traders.

A cadre of 3,200 competent LSPs and 63 SPAs was built up. In the initial stage, the farming communities selected the potential LSPs from the villages. Later on, the project, with the involvement of the public extension agencies, selected the LSPs based on the interest and commitment from the provisional list. At the beginning, the project in collaboration with public extension agencies and private companies, organised several capacity building events (training, workshop, learning visit, field based accompaniment, etc.) for the selected LSPs. The project also facilitated LSPs to establish business relationships with public extension agencies and private sector entities. Thanks to the project, the public agencies and private sector organisations now understood the incentives and took responsibility of capacity building of LSPs and SPAs. Today, the LSPs/SPAs offer poor producers a service package comprising both technical service and business development and market access support.

Farmers expressed a high level of satisfaction with the quality and affordability of services for improved and new technologies and inputs. More than 900,000 producers were able to access and use the holistic services provided by the LSPs, which have become the main source of agribusiness support for poor producers in the region. As a consequence, producer groups and their networks have been flourishing, with more than 5,700 groups active across the different value chains today.

The LSPs/SPAs also provided training to producer groups on financial literacy and supported them in developing relevant business plans. The SPAs facilitated producer groups to share their business plans during match-making through workshops with potential Micro Finance Institutions (MFI), banks and traders. Participation in these workshops also increased awareness of traders, MFIs and banks for the needs of poor farmers and producer groups. Thus 2,500 producer groups were able to cover at least half of their financial requirements as per their business plans.

Key elements of facilitating inclusive and sustainable market systems

The project’s approach was based on the following five main elements:

Setting the strategic framework. Establishing the result and impact chains and the hypothesis linking the project’s poverty reduction objective to expected changes in the value chains required specifying the market context of each chain. Samriddhi explicitly stated and defined the rationale for selecting the value chains, and how the positions of the target groups could be enhanced and were expected to change.

Understanding the market system that the poor live and work in. The project did not conduct scientific market research, but facilitated a “diagnostic process” allowing the value chain actors to understand the wider context in terms of the socio-economic and political dimensions of how the related markets function. The assessment produced relevant concrete information, but was not meant to be a one-off exercise; the project staff periodically gathered qualitative and quantitative information for a continuous reassessment of how and why the market systems improved or stalled.

Defining sustainable outcomes. Sustainable value chain development was defined as the broadening and deepening of positive and relevant changes in the market systems beyond the duration of the interventions. The value chain analysis identified obstacles to better performance of the market systems in terms of growth and inclusiveness, and showed what should be done to get them work for all, specifically for poor and very poor men and women. Obstructive factors were found at various levels. In the private sector, the areas of market penetration, product development and outreach with low transaction cost were given special attention. In the public sector, weaknesses were revealed in outreach for sufficient and efficient services due to limited financial and human resources. At enterprise level, there was a lack of quality inputs, market access, finance, technical knowledge and skills, organised production and marketing. Based on this, the following activities were identified to get market systems working for all:

• facilitating competitive value chains for better functioning market systems,

• improving the engagement of private sector enterprises,

• ensuring equitable benefit for poor and very poor,

• enhancing gender inclusive (inclusion of female) value chain development, and

• strengthening advocacy for a better enabling environment.

Facilitating inclusive and sustainable market system changes. Facilitation was defined as the process of building trusted and lasting relationships between and among market actors, without the facilitators becoming part of the market systems, or otherwise creating dependencies of market actors in the project. The process required communication skills to build such relationships when critically analysing complex and interconnected systems. These skills were crucial in identifying key leverage points, unearthing innovative ideas and creating “win-win” situations for the market actors, and the project advisers provided the project

staff with training and regular accompaniment support to gain the respective skills. In addition, the project implemented several review and planning workshops with the project staff members.

Assessing changes. The monitoring and result measurement system had to be able to capture several process and system related changes. Outcomes resulting from interventions at market system level needed to be linked to changes at the level of each actor through value chain specific impact chains. The project therefore assessed changes at the level of producer groups, service providers, as well as other market actors. The monitoring system was based on Donor Committee for Enterprise Development (DCED) standards, which enabled the learning and decision-making process as well as the demonstration of the impact.

Shamim Ahamed & Noor Akter Naher*

HELVETAS Swiss Intercooperation

Dhaka, Bangladesh

Shamim.Ahamed@helvetas.org

* This article was prepared with the inputs from experience documents of the Samriddhi project.

References

- Hossain, M.S, M.N.A. Naher and Z.B.Uraguchi, 2014. Value chain Development for inclusive and sustainable market systems in Bangladesh. https://assets.helvetas.org/downloads/value_chain_capex_february_2014.pdf

- Dietz, H.M., M.N.A. Naher and Z.B.Uraguchi, 2013. Private Rural Service Provider System.https://assets.helvetas.org/downloads/lsp___spa_capex_august_2013.pdf

- Reza M N I, A Nath, M M Hossain, M. M Rana and Z B Uraguchi, 2014. Facilitating Sustainable Pro-Poor Financial inclusion. https://assets.helvetas.org/downloads/financial_inclusion_capex_jan_2014.pdf

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment