Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Tackling the double burden of malnutrition

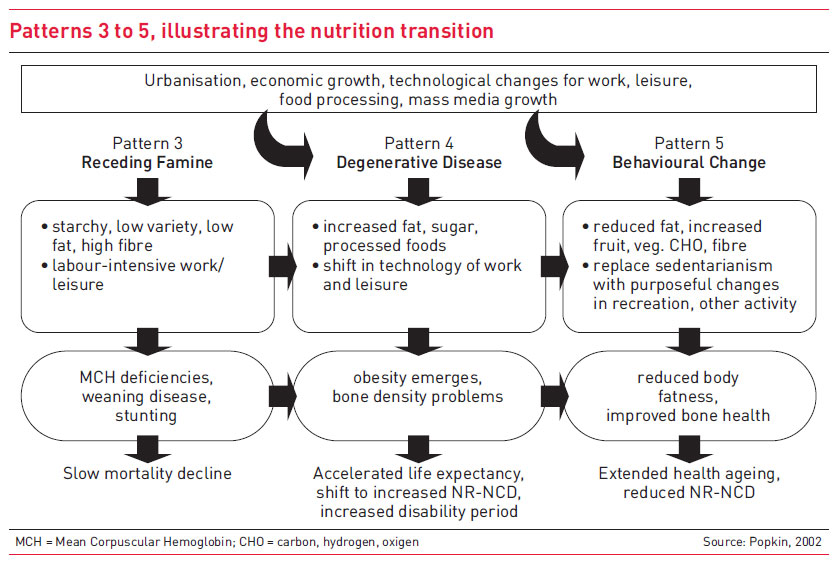

The pace of change in demographics and public health has quickened in recent years. Among other factors, urbanisation, economic growth and technological inventions have brought about changes in populations’ health and nutrition status which are described by the US American nutrition and obesity researcher Barry Michael Popkin with five broad nutrition patterns, ranging from collecting food (1), through famine (2), receding famine (3), nutrition-related non-communicable diseases (NR-NCD) (4) and, lastly, to behaviour change (5). The shift between the patterns 3 to 5 is synonymous, for many, with the term nutrition transition, and its associations between nutrition and health are shown in the Figure.

The rapid shift between the end of famine and overeating along with the emergence of NR-NCD can be found in many low- and middle-income countries, including Cambodia. This pattern shift comes along with a dietary shift from traditional, starchy, low variety, low fat and high-fibre diets towards diets with increased low-quality fat, sugar and refined carbohydrates, and processed foods – the so-called Western diet, which can also be observed in Cambodia. At the same time, activity patterns shift towards a more sedentary lifestyle, leading to a higher energy intake and a lower energy expenditure in general.

How globalisation and the nutrition transition interrelate

The phenomenon of the nutrition transition is the result of a number of demographic, economic, social and behaviour changes that affect daily life in Cambodian society. Globalisation and the implementation of market-oriented agricultural policies during the last decades have led to a more liberal global agricultural marketplace, which enabled food trade, higher foreign direct investments and the expansion of transnational food companies. Thus, globalisation affects the availability of and access to food by changing the way it is produced, processed, procured, distributed and promoted. This has led to major changes in the country’s food culture, with significant shifts in dietary patterns and individual nutritional status. High foreign direct investments in processed foods made them available on local markets, which resulted in increased consumption of these products, often also driven by aggressive food marketing adapted to the local context.

Against this background, two simultaneous mechanisms within the context of globalisation have an effect on dietary choices and consumption habits: dietary convergence (homogenisation of diets with high consumption of animal-source foods, edible oil, sugar, salt and low intake of a variety of staples and fibre; mainly driven by price) and dietary adaption (increased consumption of brand-name processed foods and meals eaten outside the home together with changes in household’s eating behaviour; mainly driven by time constraints, advertising and availability). The change in Cambodia is being brought about by the trend that fewer and fewer traditional healthy dishes are being self-prepared as more food is purchased from outside the home, where it is difficult to control ingredients and cooking procedures. Ultra-processed convenience food has become readily available even in the most remote areas, where it relieves busy mothers increasingly entering the workforce of their already heavy burden at home.

Apart from globalisation, other factors such as modernisation, urbanisation, and continued economic growth paired with increased household income and wealth have amplified these dynamic shifts in everyday lifestyle, dietary intake and physical activity patterns amongst the Cambodian population. The shift from traditional diets to Western-style diets has been a key contributor to increased obesity rates in this Southeast Asian country. As income continues to rise, individuals can afford an abundance of high-calorie convenience foods whilst at the same time becoming less active, leading to increases in obesity and obesity-related chronic illnesses such as diabetes and heart disease.

THE MANY FORMS OF MALNUTRITION

Malnutrition occurs in different forms – it is a collective term that includes undernutrition (underweight, stunting, wasting), micronutrient deficiencies and overweight and obesity, often leading to nutrition-related non-communicable diseases (NR-NCD), disproportionately affecting the poorest, minorities and people most vulnerable to food insecurity. Wasting, defined as low weight-for-height, indicates a recent and severe weight loss due to acute undernutrition, while stunting is defined as low height-for-age and results from chronic undernutrition which is usually associated with poor socio-economic status, poor health and inappropriate child feeding early in life. A child suffering from underweight, measured as low weight-for-age, might be wasted, stunted or both. Overweight and obesity on the other hand are defined as an excessive fat accumulation. Persons affected by this condition are too heavy for their height.

The double burden of malnutrition – a particular challenge for Cambodia

The new dynamics and the altered nutrition situation have led to an emerging twofold challenge called the double burden of malnutrition, meaning that undernutrition - described by wasting, stunting and micro-nutrient deficiencies - and overweight or obesity coexist within the same generation and household, and even among the same individuals throughout their lifetime. In the specific case of Cambodia, the double burden of malnutrition is characterised by high prevalence of child stunting (32.4 %, 2017) and anaemia in women of reproductive age (46.8 %, 2016), whilst NCD rates were simultaneously estimated to account for 64 per cent of all deaths in 2016, and communicable, maternal, peri-natal and nutrition conditions accounted for 24 per cent of all deaths in the same year. Six of the top ten causes of disability-adjusted life years (a measure of overall disease burden, expressed as the number of years lost due to ill-health, disability or early death) in Cambodia in 2017 were NCDs, with remarkable increases in the burden of strokes and diabetes over the last decade.

In terms of consumption patterns during the complementary feeding period, a study conducted by Pries et al. (2017) showed that a considerable proportion of the children aged six to 23 months in Cambodia’s capital Phnom Penh were fed with infant formula and powdered milk. Drinks containing high amounts of sugar (soft drinks, fruit drinks, chocolate-based or malt-based drinks) were consumed by up to 20 per cent of the children aged 12-23 months. Within the same age group, commercially produced snack foods were the third most commonly consumed food group, with a preference for savoury snack foods, such as chips or crisps. In the study sample, snack foods were more commonly consumed than micronutrient-rich fruits and vegetables. The results indicate that regular consumption of commercially produced snack foods is very common in children under the age of two years in the urban setting of Phnom Penh. Mothers said the main reasons for feeding this type of food to their children were that the child liked the snack food and demanded or cried for it. 21.5 per cent of them also believed these snacks were healthy for their child.

A study conducted in a rural community in Siem Reap (SR) province and in a semi-urban community in Kampong Cham (KC) province found prevalence of impaired glucose tolerance (preliminary stage of diabetes), diabetes and hypertension of 10 %, 5 %, 12 % (SR) and 15 %, 11 %, 25 % (KC) respectively. These findings were unexpected to this degree as Cambodian society, in particular in those two areas, is relatively poor and the lifestyle is fairly traditional. Two-thirds of the study participants with diabetes as well as half of the participants with hypertension were unaware of their condition – an alarming result given the negative long-term effects of these conditions left untreated. As obesity prevalence in Cambodia is quite low, genetic susceptibility to diabetes and metabolic adaptions to early nutritional deprivations during the Khmer Rouge time were considered as possible explanations for the study’s findings.

Addressing all forms of malnutrition with a multisectoral and multi-level approach

In order to address the problem, the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) launched the Multisectoral Food and Nutrition Security (MUSEFO) Project in the two provinces Kampong Thom and Kampot in 2016. Activities are carried out in the health, nutrition, WASH (water, sanitation and hygiene) and agriculture sectors at household, village, provincial and national levels.

With policy advice at national level, the project supports the integration of food security and nutrition aspects in national policies and guidelines. This has resulted in the country’s 2nd National Strategy for Food Security and Nutrition (NSFSN, 2019–2023) acknowledging the double burden of malnutrition within the Cambodian context and declaring the promotion of healthy diets and nutrition-sensitive food value chains as priority actions, among others. Food policy changes are seen as a major option for improving nutrition, but they will not be adequate without shifting the culture of eating. Therefore, the project has created care groups at local level that provide a platform for women to meet on a regular basis and learn about mother, infant and young child nutrition, childcare and hygiene practices, focusing on interpersonal behaviour change communication. The leaders of the care groups, who are community-based health volunteers, meet regularly with project staff for training and supervision. They are responsible for continuous training and coaching of the care group members in care group sessions and during home visits. In the sessions, the group leaders share insights on nutrition and health and encourage participants to put their newly acquired knowledge into practice at household level and within their community. Training and empowering people, in particular pregnant and breast-feeding women, and supporting efforts of citizens working together to change their communities and regain food sovereignty is key. In addition, nutrition-sensitive agricultural activities are implemented using seasonal calendars combining agricultural practices with nutrition and health information and practical cooking recipes for young children. The seasonal calendars are supporting farmers to identify the right timing and techniques for cultivation and harvest.

The MUSEFO Project looked into possibilities to promote healthy snacking options. It worked together with food vendors from the target areas to develop recipes for healthy snacks such as brown rice waffles with moringa, purple sweet potato smoothies or ice cream with pink dragon fruit and unsweetened coconut milk. The recipes were tested with the target group and are currently compiled in a recipe booklet for the wider population.

Forming of an alliance to fight NCDs

Beyond the activities of the MUSEFO Project, GIZ has established the Cambodian NCD Alliance (CNCDA). The CNCDA was officially launched in March 2019 to call for greater action to tackle the rising burden of NCDs, and build a new platform for collaborative action. The mission of CNCDA is to put NCDs firmly on the political agenda, by joining forces with those working on NCDs and their risk factors to build a platform for collaborative advocacy and a common agenda to accelerate action and mobilise resources necessary to prevent and control NCDs among the Cambodian population. The CNCDA is currently an informal alliance, with its secretariat based in Phnom Penh. So far, the CNCDA has 22 members consisting of civil society, bilateral and multilateral agencies, academia, researchers, relevant ministries and government agencies, patient groups and people living with NCDs who share its mission and vision.

The CNCDA has developed its first annual Action Plan to provide a framework for NCD prevention and control activities. The focus was initially on accelerated action on the prevention of NCD risk factors and sustainable financing for NCDs. However, the impact of the recent COVID-19 pandemic has shifted it with the CNCDA now calling for the inclusion of NCDs in the national COVID-19 Preparedness Response Plan. The CNCDA has just been awarded its first grant by the Solidarity Fund on NCDs and COVID-19, which was officially launched mid-July 2020 by the NCD Alliance. Activities in the 2020 Action Plan include:

- Identify and recruit champions to raise awareness of key messages and advocate for greater attention to NCDs.

- Produce evidence-based policy briefs to provide information to decision-makers who support key advocacy priorities.

- Produce written content and disseminate key messages via social media channels and other communication platforms.

- Produce fact sheets on NCD risk factors and main diseases in Cambodia.

- Identify ways to increase the involvement of people living with NCDs and document lived experiences of NCDs.

- Expand and diversify CNCDA membership by establishing connections with key stakeholders across multiple sectors.

Policies and food systems must change

Many low- and middle-income countries have seen substantial economic growth in the last decades, with rising income and therefore increased purchasing power of the consumers along with changing lifestyles, making them particularly susceptible to the nutrition transition. The food industry plays a major role in the structural flaws that affect the most vulnerable groups the hardest. With new global actors such as transnational agri- and food businesses, including global and local food and beverage producers and food service companies, but also local food retailers increasingly influencing food production and subsequent food purchases, the challenges posed for obesity and NR-NCD prevention are great.

While the manifestation of the nutrition transition differs across countries and regions, there are some key interventions that can be considered for most of those countries. Overnutrition, and especially obesity, have been largely ignored in national nutrition and health strategies within those countries that are still characterised by high prevalence of undernutrition. Keeping in mind the tremendous long-term public health and economic consequences that come along with the double burden of malnutrition, rapid policy and programme shifts are needed to address all forms of malnutrition. It is well-known from high-income countries that the treatment and management of NR-NCDs is extremely expensive. Low- and middle-income countries are particularly challenged regarding allocating funds within their health budgets for treatment options as they are already struggling to provide for primary preventive undernutrition care. Currently, prevention efforts are the only feasible approach to address the upcoming epidemic of NR-NCDs in countries affected by the double burden of malnutrition. Progressive changes in government policies at national and alignment with subnational levels, law regulation and enforcement, alongside shifts in local food systems, from production to marketing, purchasing and consumption as well as individual behaviour changes are of the essence when it comes to improving the way people grow food, work, eat, move and enjoy life.

Dominique Uwira is Advisor for Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) in the Multisectoral Food and Nutrition Security (MUESEFO) Project in Cambodia. Her focus lies on the SUN Donor Network Co-ordination and Social Behaviour Change Communication.

Nicole Claasen is Policy Advisor with Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), working for the Cambodian Council for Agricultural and Rural Development. The scope of her work encompasses multi-sectoral coordination, subnational integration and advocacy work for food security and nutrition in Cambodia.

Contact: Nicole.Claasen@giz.de.

References

Misra A, Khurana L. Obesity and the metabolic syndrome in developing countries. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008; 93:S930.

Popkin BM. Global nutrition dynamics: the world is shifting rapidly toward a diet linked with noncommunicable diseases. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006; 84:28998.

Popkin, BM (1998): The nutrition transition and its health implications in lower-income countries. Public Health Nutrition 1 (1): p. 5-21.

Popkin, BM (2002): An overview on the nutrition transition and its health implications. The Bellagio meeting. Public Health Nutrition 5 (1A): p. 93-103.

Popkin, BM (2003): The Nutrition Transition in the Developing World. Development Policy Review 21 (5-6): p. 581-597.

WHO (2017): The double burden of malnutrition. Geneva: WHO.

FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO (2018): The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2018. Building climate resilience for food security and nutrition. Rome: FAO.

WHO (2018): Noncommunicable Diseases Country Profiles 2018. Geneva: WHO.

WHO (2018): Nutrition Landscape Information System (NLiS) Country Profile. Online available at: http://www.who.int/nutrition/nlis/en/, revision date: 26.11.2018.

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (2017): Country Profiles. Online available at: http://www.healthdata.org/results/country-profiles, revision date: 26.11.2018.

Pries, AM; Huffman, SL; Champeny, M; Adhikary, I; Benajmin, M et al. (2017): Consumption of commercially produced snack foods and sugar-sweetened beverages during the complementary feeding period in four African and Asian urban contexts. Matern Child Nutr 13 (S2): p. e12412.

King, H; Keuky, L; Seng, S; Khun, T; Roglic, G; Pinget, M (2005): Diabetes and associated disorders in Cambodia: two epidemiological surveys. The Lancet 366: p. 1633-1639.

Gluckman, PD; Hanson, MA; Pinal, C (2005): The developmental origin of adult disease. Matern. Child Nutr. 1: p. 130-141.

Tzioumis, E; Adair, LS (2014): Childhood dual burden of under- and over-nutrition in low- and middle-income countries: a critical review. Food Nutr Bull 35 (2): p. 230-243.

Popkin, BM; Adair, LS; Wen Ng, S (2012): Global nutrition transition and the pandemic of obesity in developing countries. Nutrition Reviews 70 (1): p. 3-21.

Godfrey, KM; Barker, DJP (2001): Fetal programming and adult health. Public Health Nutrition 4 (2b): p. 611-624.

The World Bank (2018): Statistical Capacity Country Profile. Online available at: http://datatopics.worldbank.org/statisticalcapacity/CountryProfile.aspx, revision date: 26.11.2018.

Central Intelligence Agency (2018): The World Fact Book: East and South-East Asia Online available at: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/resources/the-world-factbook/wfbExt/region_eas.html, revision date: 30.11.2018.

The World Bank (2018): Statistical Capacity Country Profile. Online available at: http://datatopics.worldbank.org/statisticalcapacity/CountryProfile.aspx, revision date: 26.11.2018.

WHO (2018): Nutrition Landscape Information System (NLiS) Country Profile. Online available at: http://www.who.int/nutrition/nlis/en/, revision date: 26.11.2018.

UNDP (2018): Global Human Development Indicators. Online available at: http://hdr.undp.org/en/countries, revision date: 27.11.2018.

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (2017): Country Profiles. Online available at: http://www.healthdata.org/results/country-profiles, revision date: 26.11.2018.

WHO (2018): Nutrition Landscape Information System (NLiS) Country Profile. Online available at: http://www.who.int/nutrition/nlis/en/, revision date: 26.11.2018.

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (2017): Country Profiles. Online available at: http://www.healthdata.org/results/country-profiles, revision date: 26.11.2018.

WHO (2018): Noncommunicable Diseases Country Profiles 2018. Geneva: WHO.

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment