Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Microfinance lending for farming in Congo – a worthwhile risk?

Life is quiet in the small village of Kinsambi on the Mansi plateau. It is rare to see a vehicle on the road, just a few goats, chickens and pigs. On plots that are sometimes only 25 square metres in size, manioc, plantains, peanuts, tomatoes and other kinds of vegetable crops are growing. Livestock farming is only of secondary importance because the farmers do not have the necessary land or, especially, water. Outside the rainy season there is very little rainfall. Today the sky is typically cloudless, and a scorching heat is making its presence felt; the roads and surrounding fields are parched.

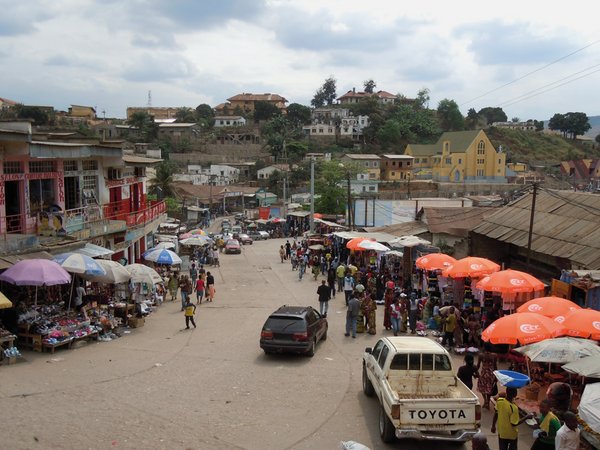

Despite the problem of irrigation, the area has potential for intensified agricultural production. The farmers themselves point out the fertile soils of the plateau, which bear two harvests per year. In good years they might be able to sell almost half of the harvest; furthermore, the port city of Matadi with its 300,000 inhabitants and bustling markets is only 45 kilometres away. Nevertheless, the majority of the harvest is used for personal consumption or saved as seed for the following growing season.

Barriers

Why is that the case? In 2011 the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) ranked in last place on the Human Development Index. What it lacks above all else is infrastructure. Although the gigantic Inga hydropower dams are only 15 kilometres away, there is no electricity here. Farmers are forced to spend a lot of money on powering water pumps. Mechanisation of production is non-existent – it would cost 200 US dollars a day to hire a tractor. A further problem is the availability of any means of transportation. Although the road to the province’s capital is asphalted and in good condition, few inhabitants can afford to own vehicles. Only from time to time, a trade intermediary shows up in Kinsambi and the surrounding villages on the plateau, in order to buy products directly from the producers in situ.

Shortage of capital as a starting point

“With loans we could do something about the existing obstacles,” says one farmer during a meeting. “We could club together with neighbours and hire a tractor. We could invest in an irrigation system and buy diesel for the water pumps. We could pay labourers to help us with preparing the fields.” But there is no culture of credit in the rural districts of Congo, which makes it hard to obtain the necessary capital for accessing markets and selling products, for investing in machines and managing soils more productively, for building storage facilities and minimising crop failures.

Some farmers are certainly aware of the risks entailed by loans, both to customers and banks in rural areas: “If we had taken a loan in the 2011/2012 harvest season, we would not have been able to pay it back,” comments one. That was a season when a lack of rainfall led to massive crop failures in the region.

Nevertheless, the question is how financial institutions can better serve the needs of rural areas and agricultural production and counteract the shortage of capital by providing adapted financial products.

New developments in the finance sector

Since the start of the new millennium, the finance sector in DRC has been growing, favoured by a relative stabilisation of the political situation. In a joint initiative the state, donors and finance institutions are endeavouring to simplify access to investment capital, and thus encouraging the development of the private sector. Finance institutions have only built up a modest presence so far, confining their activities to a few large cities. In 2011, only around 2 per cent of the population were customers of banks.

The expansion of the microfinance sector is aimed at ensuring “financial inclusion”: with an offer that is tailored to micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs), even small investors will be given the opportunity to invest or borrow money securely and on regulated terms. The trend in the DRC as elsewhere is moving towards professionalisation of the sector, i.e. growth spearheaded by accredited banks and microfinance institutions (MFIs) with international experience, and a concentration of finance cooperatives in mutual associations with nationwide coverage. The central bank, whose role is to regulate the sector, has closed down inadequate cooperatives and MFIs in the past few years and attempted to establish quality standards. The majority of donors, like Germany’s KfW Development Bank, are supporting experienced finance companies who have made a commitment to the “double bottom line” (see Box below). The aim is to create jobs in supported MSMEs so as to improve the situation of the poorer people on a broad scale.

Double bottom line – microfinance joins the debate

The double bottom line involves linking financial with social objectives throughout company activities. The original idea of microfinance – money for the poorest, so that they can free themselves from poverty – is now combined with the principle of the financial independence of institutions. On the one hand, this leads to high interest rates to compensate for the transaction costs of serving numerous small customers and to amortise possible defaults on repayment. On the other hand, the maxim of profitability ensures that the safest possible customers are recruited after detailed checks of their credit standing, to minimise the risk of over-indebtedness. Consequently, the microfinance sector tends to strive for larger customers, where the ratio of transaction costs to returns is more favourable.

Production and processing still cold-shouldered

Following this logic, the majority of MFIs are investing in cities where the high costs of setting up a new branch are worthwhile, thanks to comparatively good infrastructure and customer density. In the main, the customers are established companies who can demonstrate adequate capital resources and guarantees. The bulk of the MFI clientele are traders – from the woman who sells beans in the marketplace to electronics shops importing their own stock. The producing and processing trades (farming, crafts, refinement of raw products) have difficulty in obtaining loans, considering that their turnover is generally lower, their profit margins more uncertain and the turnover periods longer than for purchases and sales. Motivated by these same arguments, entrepreneurs are more likely to go into business as traders than to manufacture goods themselves. One consequence is the widespread absence of local products in the markets in major cities – finished products are always imported, and even vegetables and fruit in season are sourced from abroad instead of the surrounding countryside.

Barriers for MFIs

Given the size of the country, the disastrous state of the roads apart from the few primary axis routes, the intermittent power supply and perennial security troubles, it is unrealistic to expect MFIs to make rapid inroads into all the provinces and achieve blanket coverage. “We lack the expertise for agricultural lending, and in view of the high investment costs, the profitability just isn‘t there,” says a member of staff at the newly opened Oxus microfinance bank, for example. The reasons for this are multifaceted:

- High investment costs of meeting security standards, and minimal existing infrastructure.

- Few potential customers and low production output of small-scale farmers.

- No dependable sales markets for local production, no value chains.

- Inputs and production aids difficult to obtain.

- Advisory services from state agronomists barely exist.Agriculture is dependent upon external factors in the most favourable circumstances, but in these conditions itscarcely satisfy the terms of an MFI risk analysis.

No government support

The challenge of improving the production and sales conditions for small farmers by giving them access to capital is huge. Market studies looking at potential demand in peripheral provinces are a start, in order to convince the MFIs that start-up investments might be profitable. These studies are already available for a few provinces and need to be carried out in the other regions in future. It is also vital to make the government and donors aware that the agricultural sector needs support. In the words of a representative of Mecreco, a Congolese association of finance cooperatives: “Agriculture can help us to combat poverty. But up to now there has been absolutely no support for the sector. In India, finance institutions must set aside an amount for agricultural loans. Likewise in the Congo, the state should find ways to ensure the redistribution of money and opportunities across the totality of its territory.” So far the government has relied on major infrastructure projects known as “les cinq chantiers” and on special economic zones along well-connected development axes. If the aim is seriously to shift the focus onto tackling food security and poverty reduction in rural regions, too, making these the basis for improving living conditions in the DRC as a whole, reinforcement of the agricultural sector and small producers must be driven forward in the next years.

How can rural regions be supported with microfinance loans?

Bearing in mind the potential of agriculture, the domestic market, jobs in the agricultural sector and the precarious food situation in the DRC, promotion of the agricultural sector on different levels should be prioritised – ideally in the following constellation: The state creates incentives and enabling conditions for the microfinance sector by:

- offering subsidies/tax concessions for MFIs which open branches in structurally disadvantaged regions;

- expanding transport routes and the electricity supply to improve production conditions and access to markets;

- promoting producer cooperatives for the optimisation of production, storage, processing and marketing, and

- establishing an efficient advisory service.

Donors and meso-level institutions provide financial and technical support (e.g. via the Microfinance Promotion Fund (FPM) for financial inclusion) by:

- exerting influence on the government and the finance sector to promote branches and financial products in rural regions;

- tying support for MFIs to quotas for investment and lending for the agricultural sector;

- carrying out potential analyses in peripheral regions (already in progress under the auspices of the FPM).

Microfinance institutions develop adapted products:

- extending the range of provision for farmers (adapted repayment modalities, harvest insurance products);

- conducting market analyses and gathering experience from comparable countries on extending the product range and integrating neglected economically-active groups.

Investment in rural regions will not yield the same guaranteed returns in the foreseeable future as investment in urban centres. MFIs cannot operate at a loss if they want to serve customers in the long term and keep shareholders satisfied. If a share of the risks could be borne by a guarantee fund co-financed by donors, it might motivate MFIs to finance start-up business ventures and more risk-laden regions. An auditing body must ensure that the introduction of such a fund in no way distracts from the rigorous checks on customers which protect both lenders and customers from over-indebtedness.

Study and further reading

In 2012 an advisory team from the Centre for Rural Development (SLE) at the Humboldt University in Berlin carried out a study commissioned by KfW Development Bank on the effects of microfinance products on economic empowerment in the DRC. Economic empowerment encompasses an economic and a social perspective: effecting changes in profits and consumption and in the scope for decision-making about the use of resources. The results showed mild positive economic effects and limited positive social effects. Pronounced differences came to light between the genders (structural discrimination against women was exacerbated), economic sectors (trade was favoured over productive sectors) and regions (structurally weak regions were neglected).

Documentation of the study (in French):

Erik Engel et al.: Pour mieux se débrouiller? Autonomisation Économique par l’accès aux produits de microfinance en République démocratique du Congo. Berlin:

SLE 2012. www.sle-berlin. de

Erik Engel, Jakob Lutz

SLE – Centre for Rural Development

Humboldt University Berlin, Germany

sle@agrar.hu-berlin.de

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment