Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Engaging smallholders in value chains: who benefits under which circumstances?

Agricultural value chains are organisational schemes that enable a primary product to get sold and transformed into consumable end-products, adding value at each step of a gradual process of transformation and marketing. It is not only recently that the value chain concept has been entering the development debate. Already in the 1990s, supply chain and logistics management scholars as well as the school of global value chains (GVC) found that value chains play an important role in development. From different angles, these scholars looked into how developing country suppliers link to markets in the more developed world.

Recently value chains have experienced renewed interest: Development agencies as well as private companies are using them as vehicles for smallholder engagement. This new agenda is driven by the following assumptions:

- Smallholder production can easily be absorbed by national and global value chains.

- Engaging smallholders brings income and employment benefits to smallholders.

- Smallholders have the capacities and resources required to produce in response to the requirements of value chain players, or at least they can acquire them with reasonable effort and time.

- Important value chain players, such as international buyers, would be keen on supporting the engagement of smallholders.

However, there is evidence that not all that glitters is gold in value chain development engaging smallholders. The spectrum reaches from projects that successfully help farmers improve productivity and incomes complying with international buyer requirements to initiatives where only few smallholders make the race, and without reasonable benefits.

This article tries to clarify a number of issues that result from smallholder engagement in value chains and to draw some conclusions on the usefulness of the approach and critical success factors.

How can smallholders engage?

Smallholder farmers often integrate in value chains as producers in the primary production segment supplying products to national and international buyers. One example is smallholder producers in Indonesia who sell cocoa beans to traders; the traders bring them to cocoa processing plants which process them into butter and paste to be sold to chocolate makers world-wide. Taking another example, smallholder engagement in Kenya’s flower value chain sector is of a different type; smallholders disengage from independent production and become employees in flower plantation companies, gaining salaries that are well above the average of independent smallholders or labourers employed in other sectors. Smallholders can also pursue value addition, as for example in the case of rice milling in Vietnam, an activity that rice producers engage in as they see it is more profitable and complementary to the cultivation of rice. In general, three types of smallholder engagement in value chains can be distinguished:

- Engagement in independent primary agricultural production with effect on smallholder incomes.

- Engagement in dependent primary agricultural production with effect on incomes and employment.

- Engagement in value addition of agricultural products with effect on incomes and employment.

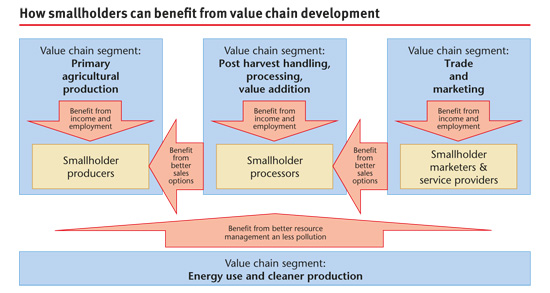

There may be further engagement of smallholders in various services that support the functioning of the value chain, e.g. transport, advisory service, etc. The Figure below provides an overview of the various effects through which smallholders can benefit from value chain development.

Who drives smallholder engagement?

A common scenario is that buyers, e.g. an international food retailer, are the main force pushing for the engagement of smallholders in the value chain. Usually, the buyers’ motive is that they are short in supply of primary products. This motive is sometimes paired with arguments of (corporate) social responsibility (CSR). In all cases, it is important to separate procurement of supplies motives from CSR-related motives. The latter address a limited group of target beneficiaries (e.g. building a school in a producer region), while the former are often able to generate a more sustainable impact on the businesses that smallholders engage in.

“Outgrower schemes” in which a buyer provides seeds and fertiliser or alternatively credit as well as agronomic know-how to “outgrowing” farmers, are a special case. The “outgrowing” farmers, in turn, produce according to a particular protocol and are obliged to deliver the product to the buyer’s collection centres where, if compliant to quality standards, the product is paid, sometimes with delay and after reducing the advanced payments.

Outgrower schemes are an efficient method to quickly provide farmers with the necessary technology and inputs to engage in value chains. However, they are vulnerable because payments and credits must be monitored but reliable accounting systems, sometimes covering a large number of smallholders, are expensive to maintain. Often, buyers are not willing to manage accounts of a large number of outgrowers relying on farmer organisations, credit schemes and/or development agencies which are also prone to mismanagement and conflicts. Outgrower schemes are particularly vulnerable because smallholders may decide to side-sell avoiding repayment of debts.

Another scenario is that suppliers of agricultural inputs such as seeds and fertiliser seek to engage smallholders in value chains to extend sales. In some cases, it is also the smallholders themselves who initiate their engagement in a value chain and seek buyers to purchase their products. Finally, there are many cases in which governments and development agencies are the drivers of smallholder engagement based on the understanding that subsidising the smallholders’ integration in the value chain will lead to social benefits. The latter has also led to the very common model of development agencies partnering with large buyers, enabling the participation of smallholders in value chains. However, the latter model has been criticised in a range of cases where the development agencies have been subsidising all activities to help smallholders comply with standards while the private buyer reaps the benefits of sourcing more higher quality products at no additional costs.

Who should initiate smallholder engagement? Often, the argument is made that lead buyers are the only appropriate drivers of smallholder engagement. However, the point is made here that any of the above, individually or jointly, can initiate such smallholder engagement, and, more importantly, that smallholder engagement is beneficial to value chain actors in general and to the smallholders in particular. This depends on a range of factors and can only be established on the basis of thorough analysis.

What makes smallholders benefit?

Engaging smallholders in value chains, e.g. via a lead buyer approach, must not necessarily result in benefits. Various studies have shown, for example, that the costs of certification can be higher than the benefits from selling a product to international buyers. Below are a number of considerations that one can make to better understand the benefits smallholders might have from value chain engagement: In the case of self-reliant smallholder production, engagement in the value chain brings the advantage that smallholders can sell a product at a fixed (and possibly higher) price. However, the engagement of smallholders often comes with an additional cost related to a new system of production and the efforts to comply with certain standards. Frequently, smallholders can only apply the new way of production after intensive capacity building and through additional investments in inputs and equipments. For example, the production of soybeans for the international market would usually require the application of zero-tillage cultivation and the purchase of Roundup Ready soy varieties. This practice requires substantial capital and larger parcels of land. In the end, it is the individual cost-benefit ratio of each farmer that determines whether engagement makes sense. For some farmers, it may be more beneficial than for others.

Common practice – the lead buyer approach

Many governments and development agencies find it difficult to choose the appropriate entry point for engaging smallholders. One common approach is to pick a lead buyer and support value chain development through that company. For example, a lead firm with connections to markets, e.g. a cassava starch processing company in Colombia, receives support through development agencies to source cassava from local farmers. The development agency helps the lead firm to provide technologies to farmers, including the arrangement of advances for production inputs such as seeds and fertilisers. Lead-firm approaches have the advantages that support by development agencies can easily be organised and all money can be channelled to one company instead of dealing with a large amount of primary producers. In many cases, however, development agencies also support the primary producers as the lead company is not able to provide technical training to large producer communities.

When training and capacity strengthening of smallholders is required, the related project costs need to be compared with the overall benefits of engaging smallholders (the accumulated individual cost-benefit ratios). If only a small number of farmers engage in a value chain and each earns a couple of dollars more, an expensive project that fosters the engagement of these smallholders may not be justified.

Some practitioners in development argue that there is often no alternative to an engagement in the value chain following a “grow or perish” logic. Indeed, local markets may sometimes not be an alternative for products that only get appropriately remunerated when they enter global value chains. However, smallholders often benefit from local markets where products of less quality can be sold parallel to value chains to which the better-quality products can be channelled. For example, second-grade mangoes from Ghana that do not meet export criteria can be sold on the local markets, sometimes at even higher prices than the first-grade export mangoes. In all cases, engagement in value chains can be a necessary condition for smallholders to maintain agricultural production when they provide a sure market outlet for products.

It is also important to balance the effects of engaging smallholders in the various segments of the value chain. Employment created at the level of processing (for example a couple of hundred jobs) may constitute a small benefit in relation to tens of thousands of smallholders benefiting from higher prices for their products. Another consideration is that employment in regions with only underpaid jobs may provide an important push to the labour market. Contrarily, if the salary lies minimally above other job opportunities, the benefit for workers may be negligible. Employment targeting women labourers can be important for gender empowerment.

In summary, the main parameters to be taken into consideration to evaluate the benefits from smallholder engagement in value chains are the following:

- the product price being paid to smallholders,

- the costs of smallholder production complying with buyer criteria,

- the costs of training and capacity building necessary to enable smallholders engaging in value chains,

- the number of smallholders that will be able to engage in the value chain (also in relation to the ones that may fall behind),

- the employment effect on engaging smallholders in primary production and other segments of the value chain.

Success factors

What works and what does not in engaging smallholders in value chains? This question is at the heart of many debates among development agents and value chain developers. Here are a number of recommendations based on the author’s experience:

- Engagement of smallholders can work for all value chains except for those ones in which smallholders find it too difficult to produce according to the required standards or where doing so requires just too much in terms of efforts and capital. Possibly, with the exception of some individuals, a smallholder community will not be able to produce sophisticated products such as Swiss watches or Kobe beef. However, smallholders around the world should be able to engage in the production of fruits, vegetables, cereals, roots and tubers and pulses as well as animal products for national value chains and export, and many studies have shown that they can even be more efficient in doing so than large producers.

- The integration of smallholders in value chains works well where the “engagement rent” provides a substantial benefit that is significantly higher than the benefit from producing while being excluded from value chains. In other words, the effort of engagement has to pay off and there needs to be a clear perception about this fact among the smallholders.

- The engagement of smallholders usually requires substantial investments in capacity strengthening. Smallholders often live in a reality where risk aversion and scarcity of resources prevail. Changing the way of production requires time, continuous coaching, eventually some subsidies and interaction among smallholders as well as with peers to build trust in and knowledge about the new production procedures.

- Initiatives that only have smallholders complying with buyer standards are unlikely to produce benefits for smallholders. They should be matched with efforts that help smallholders improve their businesses through cost reductions and better organisation of work. For example, large processors of dairy products have learned that simply focusing on smallholders’ compliance with quality criteria does not help extend the procurement of milk. In response, they have engaged in advisory services which help farmers to improve the quality of milk while also rendering milk production more profitable.

- Engaging smallholders in value chains does make sense where the market for the final product is large enough to include a reasonable number of smallholders. If the majority of smallholders are left out, engagement schemes will rather cause frustration and disequilibrium in production areas. This argument can be extended to some of the niche market products such as specialty foods and organic and fair-trade products. If such products only benefit a very small part of the smallholder population, leaving the majority without income options, there is not much sense to pursue them.

- Contractual arrangements help to fix commitments of buyers in outgrower schemes. In most cases, however, smallholders may not appreciate the logic of written contracts, which are also difficult to enforce in the socio-cultural environment of many developing countries. Instead, building trust between buyers and smallholder producers is of paramount importance and leads to non-written agreements that build the basis for sustainable businesses.

- In cases where lead-buyers and suppliers collaborate with governments and development agencies, the partnership needs to be thoroughly negotiated, and the investment of the private sector should be clearly earmarked. The details should be fixed in a contractual arrangement. In no circumstances should governments and development agencies embark on quick arrangements that favour a single buyer or even guarantee individual buyers exclusive purchasing rights. Often, options exist to work with networks of buyers, enabling integrated value chain development benefiting a whole spectrum of value chain partners.

Conclusions

Engaging smallholders in value chains can generate benefits for smallholders as well as for buyers, suppliers and other actors in the value chain, but it does not have to. Some of the conditions that lead to real benefits for smallholders have been discussed above. However, a satisfactory answer to the question of whether the “engagement rent” is high enough can only be given on a case-by-case basis.

Frank Hartwich

Agribusiness Development Branch

United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO)

Vienna, Austria

f.hartwich@unido.org

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment