Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Access for women – building up a system of rural private service providers

Should you walk along one of the country lanes that connect hamlets in Rangpur and Rajshahi district in northern Bangladesh, you are likely to see long lines of green herbs growing on the verge. Bicycles, rikshaws and the odd motorbike use these lanes. The plants are common medicinal herbs such as holy basil, creat or malabar nut. Today, women plant herbs along more than 1,000 km of lanes.

One major constraint for extremely poor households striving to develop economically is lacking access to services. They need quality inputs for agriculture or livestock, knowledge on improved technologies and practices and the skills to use them. Skills and networks to develop and manage their market linkages as well as suitable financial products and services are also vital. Government extension services have their capacity and resource constraints, and poor households fall off the radar of these services, particularly if they have little or no land.

Samriddhi (stands for prosperity in Bangla language) was a project of the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation that was implemented by Helvetas Swiss Intercooperation. The project grew out of two predecessor projects. Samriddhi’s first phase covered the period 2010 to 2014. The project’s goal was to contribute to sustainable well-being and resilience of poor households through economic empowerment in Rajshahi and Rangpur Divisions as well as in the Sunamganj District in the north of Bangladesh. The project was based on the impact logic that making public and private services available for business development empowers and capacitates, that poor people are to access these services and that if an enabling environment for pro-poor economic growth exists, poor people can generate additional income and overcome their poverty situation in a sustainable manner. Samriddhi applied an explicit market systems approach and aspired to reach one million households through its interventions by April 2014, focusing on poor and extreme poor men and women in Sunamganj District in the north of Bangladesh.

Samriddhi sought to improve the well-being of poor and extreme poor households (see Box). Its predecessor projects had realised that access to services was a major constraint for poor households, and had already started to experiment with private, local service providers. The system evolved over the years from individual service providers who first voluntarily shared their skills and knowledge with neighbours but then charged a fee for their services. The initial focus was on technical training of poor farmers and shifted towards enabling access to lucrative markets for poor and extreme poor households by facilitating linkages with market actors. A successful business model for private rural service providers has to offer relevant services to market actors, i.e. poor producers and traders.

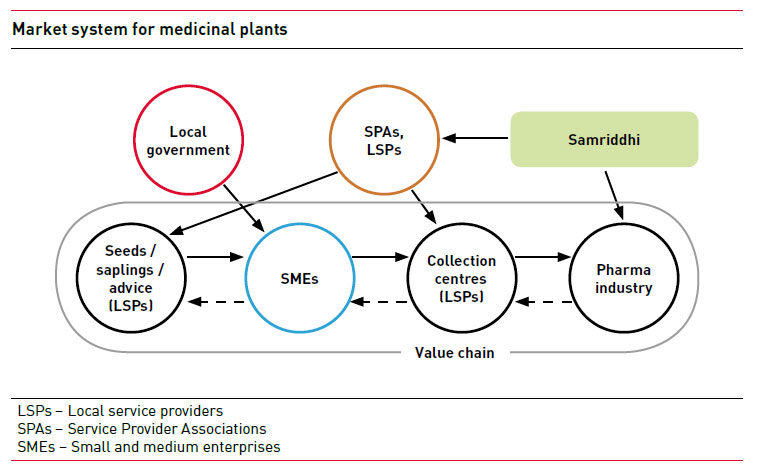

Local service providers (LSPs) are men and women with experience in agriculture or related fields and who live in the community they work in. They started to organise themselves in Service Provider Associations (SPAs) with around 40 to 50 members each. SPAs represent the interests of LSPs, providing on-going capacity building for their members and monitoring and identifying market opportunities for poor producers. LSP members motivate poor and extreme poor to form and organise into groups seen as small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Other roles of SPAs include linkages with private sector actors supplying farm inputs (seeds, veterinary medicine, crop protection chemicals). Moreover, the SPAs link to output markets and connect their LSP members for training provided by private sector companies. SPAs also link SMEs with financial service providers such as micro-finance institutions and banks. SPAs and SMEs sign service agreements defining the scope of the support poor producers need and the price of the services. Furthermore, the SPAs generate their income from commissions on the fees of service providers, input supply and some outputs and rental fees for agricultural equipment which the SPAs own. LSPs provide a service package to poor and extreme poor in support of their enterprising activities in selected value chains and subsectors. By 2015, more than 4,000 trained LSPs were working in the Samriddhi project area, 21 per cent of them women. Half of them work full-time and can manage their livelihood from their income. They have provided direct services to over 650,000 people, with an additional 350,000 benefiting indirectly.

Samriddhi’s underlying assumption was that once project support was withdrawn, LSPs supported by the SPAs would continue to form and assist new SMEs, driven by their financial interest to obtain fees and commissions. One explicit goal of the Samriddhi project was to strengthen women’s economic empowerment. It became an element in the project cycle, the logical framework, the indicators and baselines. Women in northern Bangladesh are particularly constrained by limited mobility, lack of decision-making power and the time they need to manage the household. Selecting suitable value chains and existing women LSPs have played an important role in the process of economic empowerment of women.

Providing access to public land

In 2007, the predecessor project of Samriddhi brought together producers, traders and buyers. The pharma company ACME expressed interest in purchasing bashok, (Adhatoda zeylanica, Malabar nut), tulsi (Ocimum sanctum, holy basil) and kalomegh (Andrographis paniculate, creat). Cultivating medicinal herbs for ACME could have been a real opportunity for women, generating good income and requiring only a few hours of work during the day. The problem was that many of the poor households did not own or had no access to land, or the land was unsuitable for growing medicinal herbs (e.g. contaminated with pesticides).

Roadside and public fallow land is owned by the state. The union parishad (local government) is expected to lease such land to landless people. But all too often, it is grabbed by local elites. Rural communities lack the knowledge and confidence to approach local officials and negotiate the leasing of public land.

However, advocacy and negotiation skills improved through training sessions enabled the SPAs to discuss leaseholds for medicinal herb production with local councils.

The initiative took off once private pharma companies agreed on co-financing and conducting technical training for LSPs and establishing collection centres for aggregating, drying and primary processing carried out by producers. Village-based collection centres were important for women producers who would have been unable to travel alone beyond the village boundary. Eventually, the initiative gained the support of local government officials, and groups of poor households were issued leasehold contracts.

Poor households took up medicinal herb production with the support of LSPs and their SPAs. Pharma companies increased and expanded financing collection centres in more areas, enabling more and more women to sell their produce at the collection centres and directly receive payments. While the project no longer provided inputs, companies raised prices of the producers’ goods. Furthermore, ACME has been offering a prize of at least 10,000 Taka (1 Taka is equivalent to 0.01 euros) to the group producing the highest amount of herbs.

“Whatever the producers are able to provide, we will buy” for two main reasons – sourcing locally is much cheaper and we get higher quality, as the inputs are more readily controlled,” says Abdul Salam, Assistant Manager in ACME. The company insists that no pesticides are used and that only organic fertiliser is applied. And it makes a special effort to support landless women.

The experience of women producers – Polashbari Medicinal Plants SME

This group has 21 members 17 of whom are women. In 2012, the SME started to cultivate bashok along village roads for which they obtained a leasehold from the local council. In the second year, they started to intercrop tulsi in between bashok. With the income from the bashok harvest in the previous year, they have leased crop land and are cultivating kalomegh and ashwaghanda. Labour input is small – group members estimate that they spend an hour a week looking after the plants. Bashok leaves can be harvested three times a year and are dried and delivered to the collection centre.

The group generated a total income of 6,000 Taka in their first year. The following year, their sales went up to 50,000 Taka. In 2015, they harvested 20,000 kg of bashok at a value of 650,000 Taka. The income during the initial phase was saved and invested in expanding the following year’s production.

Nur Un Nahar Begum, a member of the Polashbari group

Nur Un Nahar Begum is now in her early thirties. She and her husband were landless and homeless when they got married. Keen to improve their situation, Nurun Nahar took out a small loan from a micro-credit organisation to buy a sewing machine and start tailoring. With the money made from tailoring, the couple managed to buy some land for 20,000 Taka. Then Nurun Nahar heard about cultivating medicinal plants and started growing herbs along roadsides with the Polashbari group. In addition, she set up her own small nursery, producing 1,000 plants selling at three Taka a plant. She estimates that the medicinal plants and her sewing each bring her a monthly income of about 6,000 to 8,000 Taka. With this income, she has installed a hand-pump for drinking water and bought some livestock.

Nur Nahar, a Local Service Provider

LSP Nur Nahar is a resident of Polashbari, and was trained by the private company ACME in medicinal plant cultivation and handling. Once a year, ACME extension workers, including LSPs, are invited for a workshop to update them on new technical and market developments. Nur Nahar operates a nursery on leased land on which she produces seedlings of kalomegh (creat) and ashwaghanda (Indian ginseng), which she sells to SMEs. She conducts training workshops on herb cultivation for SMEs in her area and meets with them at least once a week. She charges only for formal training events.

The LSP operates a collection centre to which 3,500 SME members deliver five species of medicinal plants. ACME has provided the LSP with quality standards for the dried plants and the methods to measure the quality of the goods she checks. If required, the LSP will dry the material further. She then cleans, packs and stores it. ACME collects the material once a week. Payment is a week later, and the LSP gets three Taka commission per kg of dried material. Her income as an LSP has increased to 20,000 Taka a month. “I have gained a lot of experience and confidence as well as networks to work beyond our communities,” she says. “With the help of my SPA, we explore new markets for medicinal plants. For example, we are interested in marketing tulsi tea as a new product and expanding medicinal plant cultivation activities to other areas of Gaibandha District. We want to include more poor and extreme poor households. By supporting them, we are supporting our communities and ourselves. We will lease land for cultivating highvalue medicinal plants. We are positive about the future.”

Potentials for scale

The demand for medicinal plants is high, and the potential supply through the planting of under-utilised roadsides by landless women is also high. Yet, there can be an inverse correlation between reaching scale and reaching women – in that once a value chain is perceived to have major economic potential and/or requires a presence in markets a little way from the producer, it is more likely to be dominated by men.

By the end of 2015, about 60,000 producers were growing medicinal herbs on roadside and fallow land. Most of them were disadvantaged and poor women.

Additional private companies and small enterprises joined producing and processing medicinal herbs, expanding their geographical coverage beyond the initial northern part of Bangladesh. Better horizontal and vertical coordination of actors led to product and process upgrading either through better organisation of the production process or the use of improved technology. Poor and disadvantaged women and men diversified the species of medicinal herbs. They started growing bashok and then added four species: kalomegh, holy basil, asparagus and ashwaghanda.

For its implementation of the Samriddhi project, the Second Herbal World Global Exhibition and Conference, held in Malaysia in September 2014, conferred Helvetas an award. International and national actors and players – from development agencies to international organisations – have started replicating the success of the initiative.

Challenges for the future

The main challenge will be supporting women producers in gaining a fair wage reflecting the value of the crops produced. Women engaged in value chains generally welcome the opportunity to make some money, often to supplement their income. However, promoting exploitation or gross inequality in benefit distribution is a different matter. Thus, for example, whilst the rapid growth of the medicinal plant value chain may be considered a huge success in terms of giving many landless women the opportunity to earn a little cash, more could still be done to increase gains for women producers. The benefits of private companies in sourcing medicinal herbs nationally are huge when compared with sourcing medicinal herbs through supply chains from India, Nepal or China.

Through Samriddhi’s facilitation, private companies involved in medicinal plant production have decided to increase the price for herbs, in addition to substantially contributing to the expansion of multi-purpose collection centres. These centres closely located to producers accelerate the delivery of leaves to the company, and vice versa for the company to supply inputs and advice. Thus overall, they enhance producer productivity while making matters easier for the women.

Martin Dietz works as Senior Advisor to Sustainable and Inclusive Economies at Helvetas Swiss Intercooperation in Zurich, Switzerland.

Contact: martin.dietz@helvetas.org

Further reading:

Md. A. R. Bhuiyan (2011). Analysis of the pharmaceutical industry of Bangladesh: its challenges and critical success factors. Bangladesh Research Publications Journal. V, 142-156.

Zenebe B. Uraguchi, Sabiha Sultana, Mostafa Islam, Shamim Ahamed (2018). "Inclusive Systems" in Practice: How Medicinal Herbs Supported the Livelihoods of Poor and Disadvantaged Communities in Bangladesh. Helvetas Swiss Intercooperation

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment