Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Do import restrictions really benefit the local poor in West Africa?

Over the last 20 years imports of chicken have increased in many West African countries. Since local production cannot keep up with the growing demand, imports are used to close that gap in supply. In the case of chicken, those imports mainly come from the European Union (EU), but also from the USA and Brazil.

However, cheap imports of chicken to West Africa are discussed controversially. Developing countries may benefit from such cheap imports, as they help to keep domestic prices low and improve access to nutritious foods for the poor who might otherwise not be able to afford much protein. Nevertheless, critics point out that local producers, including smallholders, may struggle to compete with the lower prices of imported chicken and thereby lose one of their sources of income.

In the past, to protect the local industry and with it producers and farmers, a few African countries have imposed policies that restrict such imports. Referred to as protectionist trade policies, they have been implemented e.g. in Nigeria and Senegal, either by increasing import tariffs or banning chicken imports altogether. Although different trade agreements such as the Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) as well as regulations by the World Trade Organisation (WTO) govern such trade policies, exceptions exist under specific conditions. Health concerns or disease control allow for different regulations. For instance, Ghana recently imposed a partial import ban on poultry products from five European countries following an avian influenza outbreak. In order to analyse the effects of such protectionist trade policies, we designed two scenarios – a 50 per cent import tariff for chicken and a prohibitive import tariff that would lead to zero imports, equivalent to an import ban for chicken. Taking Ghana as an example, we analysed the effects of these two hypothetical import policies on domestic households’ chicken sales, consumption and overall welfare. By focusing on household consumption and production instead of larger commercial farms while also distinguishing between poor and non-poor households, the study helps to draw conclusions on whether or not import restrictions would be a pro-poor policy.

Ghana’s poultry sector

The poultry sector in Ghana is characterised by large and medium-sized commercial farms which focus mainly on egg production as they have gradually been pushed out of the market for chicken meat by the cheaper imported competition. Most of the local broilers in Ghana are reared by small- and medium-scale farms for home consumption and selling on the market. Reasons for the lower competitiveness of local producers include lower productivity, high energy and transport costs, as well as high feed costs. In Ghana, much regionally grown feed is used, which of course costs more than the cheap soy imports chicken in the EU are often fed with. For comparison, farmers in the EU benefit from subsidies, and European consumers have a strong preference for certain chicken parts only, such as breasts, meaning that other parts are often exported at low prices.

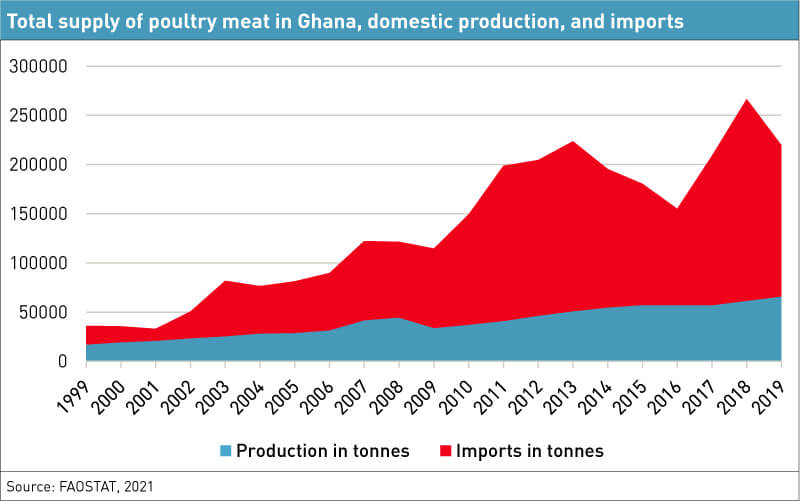

To increase productivity and competitiveness in the local poultry sector, the Government of Ghana has implemented various support programmes, including input subsidies and trade restrictions, over the years. In 2015, import tariffs for chicken and other types of meat were raised to 35 per cent in accordance with the Common External Tariff (CET) regulations of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). However, this did not lead to long-term decreases in imports, and imported quantities still remain high (see Figure).

In 2019, average annual per capita meat consumption in Ghana was 9 kilograms. This is well below the world-wide average, partly because the majority of the animal protein consumed stems from fish. However, consumption levels are rising steadily, and chicken meat in particular is popular among private households but also restaurants and hotels. Most of the chicken consumed in Ghana is imported from abroad; imports accounted for three-quarters of the total poultry supply in 2019. Next to that, imported chicken is about 40 per cent cheaper than domestic products. The two product types also differ in terms of freshness, taste, convenience and other attributes, as imported chicken is sold mostly pre-cut and frozen, whereas local chickens are sold fresh, as whole birds and often live. Ghana, South Africa and Angola are the biggest importers of chicken in sub-Saharan Africa.

Household consumption and production

Our study (see Box below) draws on data from the 7th round of the Ghana Living Standards Survey (GLSS7) from 2016/2017, a nationally representative household survey with about 14,000 household observations. The data includes information on chicken consumption and production, while distinguishing between consumption of fresh and frozen chicken. Based on market reports and other literature, it is fair to assume that the frozen chicken meat is imported, while the fresh meat is domestically produced. Additional local market price data were also collected in 2016/2017 as part of the GLSS7 and used to compute regional chicken prices.

Study framework

To analyse the effects of the two hypothetical policy situations, a 50 per cent import tariff and a protectionist import tariff, we use a partial-equilibrium model of imported and domestic chicken supply in Ghana, assuming that other sectors of the economy would be unaffected. This simplified approach comes with a few limitations (see below) but still offers the possibility to examine welfare and distributional effects at the household level. The model assumes that higher import tariffs would increase the price of imported chicken while decrease or completely stop imports – depending on the scope of the tariff. Although imported chicken and domestic chicken are not perfect substitutes and differ in a few characteristics, demand for domestic chicken will nevertheless increase by a certain factor. This factor depends on the tariff, import price and quantity changes, and the elasticity of substitution between imported and domestic chicken products. Based on the shift in demand for domestic products, we compute price changes for chicken using own-price elasticities of demand and supply.

The changes in market supply and consumption for both scenarios are calculated for each individual household. The changes in household consumption and chicken sales are then added up to get the overall welfare effect using the equivalent variation (EV). It measures the amount of money transfer that would be needed to lift the household to the new level of utility at the initial price levels.

Limitations of the analysis include, first, the simplified assumption of fully separable market and household decisions, which may in reality not be the case – especially in semi-subsistence settings. Second, price elasticities of demand and supply are point estimates, which are usually

not optimal when modelling larger price changes. Third, the results presented here can probably best be interpreted as medium-term effects of higher import tariffs, whereas short- and long-term effects may possibly differ. Finally, this study looks at household production only. Price effects also affect commercial poultry enterprises, which could affect household welfare through labour markets and wages. Results should be seen as tentative estimates of effects that can be expected from import restrictions for chicken in Ghana, but should not be over-interpreted as precise measurements.

Descriptive statistics show that around 43 per cent of all households consumed any chicken in 2017. At 36 per cent, frozen chicken consumption is much more common than consumption of fresh chicken (6 %). Around 15 per cent of all households owned chicken, either for the production of eggs or meat. Only 4 per cent sold any chicken during the 12-month survey period. The proportion of households hurt directly by cheap chicken imports is therefore rather small.

Regarding the distribution across rural and urban areas, rural households are more likely to own chicken and to sell any chicken than urban households, where only seven per cent own chicken. Consumption-wise, urban households are more likely to buy chicken from the market – either frozen or fresh – than to consume their own chicken. In both rural and urban areas, poor households are more likely to sell chicken and consume their own chicken than non-poor households. To identify poor households, we used the official poverty line, as defined by the Ghana Statistical Service (2018) for the GLSS7 data. A household is defined as poor if its consumption expenditures are below 1,761 Ghanaian cedi per adult equivalent and year.

Effects of higher import tariffs on households

In the first scenario, with an increase of the import tariff on chicken from the current 35 per cent to hypothetical 50 per cent, prices for chicken meat would rise by about 11 per cent for imported and 6 per cent for domestic chicken, respectively. In the second scenario, with a prohibitive tariff, prices for imported chicken would increase so much that this market segment would cease to exist, and imports would drop to zero. Prices for domestic chicken would then rise by 34 per cent. These new prices would affect consumption and production of chicken in Ghana as follows.

On the consumption side, only those households who purchase chicken products from the market would be affected. In the first scenario, consumption of imported chicken would decrease by 6 per cent, whereas consumption of domestic chicken would decrease by 3 per cent. In the second scenario, the changes are more drastic, as consumption of imported chicken would decrease by 100 per cent and consumption of domestic chicken by 17 per cent. While consumption would decrease, as expected, market supply levels among those households that sold any chicken would increase. In the first scenario domestic chicken sales quantities would increase by 3 per cent. In the second scenario, sales quantities would rise by 17 per cent. Accordingly, average incomes of these households would increase by 22 per cent and 74 per cent in the two scenarios, respectively. While these are large effects, they only affect a small proportion – about four per cent – of all households as the rest are not involved in chicken sales.

Welfare analysis

As expected, higher import tariffs would lead to welfare losses on the consumption side and to welfare gains on the supply side. The proportion of households that would gain from additional import restrictions – those who produce chicken – is much smaller than the proportion of households that would lose as consumers.

Thus, the average consumption losses would be much bigger than the average gains from additional sales, meaning that the overall welfare effects of higher import tariffs would be negative. The total negative welfare effects would be much larger with a prohibitive import tariff than with a 50 per cent tariff, as with a prohibitive tariff, the market for imported chicken would cease to exist. Overall effects in both scenarios would still be relatively small. This is true for all household types, poor and non-poor, as well as for those living in rural and urban areas. There are however differences in the scope of gains and losses. It should be kept in mind that the proportion of households selling chicken might potentially increase in the long run with consistently higher market prices.

Effects on poor, non-poor, urban and rural households

Non-poor households would suffer more from chicken import restrictions than poor households, as non-poor households in all groups tend to purchase more chicken from the market. That means they depend on the price of chicken more than those households who consume a larger share of their chicken from their own production. However, the role of food prices is not the same for poor and non-poor households. Therefore, we also express welfare effects relative to households’ total food expenditure. In both scenarios and for all groups of households, the total welfare losses would account for less than 2.3 per cent of total food expenditures. The main reason for this relatively small effect size is that chicken consumption, production and sales quantities are small for the average household in Ghana. For comparison, we also analysed the welfare effects when considering only households that consumed or produced any chicken. In such a case, the welfare effects increase in magnitude, but the direction of the effects remains unchanged. This means that at least in qualitative terms, our results may also hold if chicken consumption in Ghana continues to rise. This is also an important notion for those other African countries where the consumption of chicken meat plays a larger role than it currently does in Ghana.

Are import restrictions pro-poor?

Given the negative welfare effects of both hypothetical scenarios, additional import restrictions for chicken cannot be considered a pro-poor policy in general. Import tariffs do not seem to be an appropriate way to protect producers of chicken in Ghana from cheap imports, because only a small proportion of households are involved in production and the majority of them are net consumers who would be negatively affected. Targeted support measures, for example through technical assistance or direct income transfers, could be a better strategy. Overall, cheap chicken imports do not seem to be as harmful for poorer Ghanaian households as often claimed, and without access to alternative protein sources, cheap imported chicken products contribute to improved nutrition of income-restrained households. Furthermore, policies to strengthen local infrastructure, technologies, and institutions are better suited to promote sustainable development than import restrictions.

An additional question is also whether it would really make economic sense for countries in Africa to foster a commercial broiler sector for which developing international comparative advantage will be very difficult under current conditions. Fostering other agricultural sub-sectors for which African countries have stronger comparative advantages (including mostly raw and unprocessed products, like cocoa and its derivatives) would probably make more sense economically and socially.

Trade discussion

Trade liberalisation describes the reduction or abolition of trade protectionist policies, such that countries can trade goods with each other more freely. The existing literature on trade suggests that trade liberalisation has mostly positive effects on incomes and can reduce poverty in general. In theory, liberalising trade by reducing trade barriers decreases prices for consumers and increases market opportunities for producers. Protectionist policies like tariffs or other trade barriers, on the other hand, can lead to higher prices and profits for domestic producers but at the same time increasing costs for consumers, because imported products increase in price and decrease in quantity supplied. Trade barriers can also have unintended side-effects. In Nigeria, for example, a complete ban on poultry imports is now leading to rising incidents of border smuggling, thereby undermining domestic price targets as well as food safety. Since poor people spend a larger share of their income on food, higher prices hurt them much more than others. Whether a total welfare effect of a policy is positive or negative depends on the specific situation of the country or household. Net producers benefit from higher profits, while net consumers are hurt by higher consumer prices. In the African context, many smallholders, accounting for a large share of the poor, are net consumers of food – they buy more food than they sell. Higher tariffs on food imports are therefore not expected to benefit them.

Isabel Knößlsdorfer completed her doctoral research at the Department of Agricultural Economics and Rural Development at Georg-August University of Göttingen, Germany.

Contact: Isabel.knoesslsdorfer@uni-goettingen.de

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment