Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

High-hazard business

The global market for agricultural crop protection products is highly concentrated. The four largest manufacturers (see box) now share an estimated 72 per cent of the global market, provisionally valued at 69 billion US dollars (USD) in 2022 by S&P Global, the leading market analyst. Twenty-five years ago, the top four’s share was still below 30 per cent. Recently, business has been especially lucrative. The companies have successfully profited from price rises which more than compensate for higher raw material and energy costs. Just some of the factors behind this have been high demand due to supply chain bottlenecks and extreme weather conditions brought about by climate change.

Today, the market leaders in the crop protection market are the Syngenta Group, headquartered in Switzerland, the German groups Bayer and BASF, and the US-based Corteva corporation. Syngenta Group, formed in 2020 from the merger of the Swiss firm Syngenta with agrochemical companies from Israel and China, dominates around 30 per cent of the global market on its own. The two US corporations Dow Chemicals and Dupont had already merged in 2019, combining their pesticide and seed businesses in Corteva. And in 2018, Bayer had taken over the US giant Monsanto and sold parts of its business to the chemical company BASF, which then also entered the seed business.

These mega-marriages have allowed the dominant corporations to consolidate their lead over the growing competition and perfect the combination of agrochemical and seed business they have banked on since the mid-1990s. Back then, chemical and pharmaceutical companies were beginning to absorb numerous seed producers. In the meantime, the same mega-corporations have come to dominate both sectors.

For many years, sales in the crop protection market have shown a steady global growth rate of around four per cent per year. This is not evenly spread across all regions of the world, however. In Europe, for example, sales of crop protection products have stagnated for years and are even declining in some countries. The growth is primarily happening in South America and Asia. In the last 20 years, the quantity of pesticides applied in Brazil has increased by over 340 per cent, and in Bangladesh by almost 390 per cent. Other countries like China, Thailand and Argentina are also registering strong rates of growth. Pesticide use in Africa is the lowest by far, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), with an average of less than 0.4 kilograms per hectare of cropland – compared to the world-wide amount of around 2.6 kilograms per hectare. However, the industry has long had the African continent in its sights as another important growth market. According to the FAO pesticide figures, based albeit on incomplete data, the amounts used on the African continent have increased by more than 57 per cent since the turn of the millennium.

Not only have volumes of pesticides risen in the countries of the South, but many agrochemicals are in widespread use which have been banned within the EU since the authorities have designated them harmful to the environment or human health. These include substances suspected of causing cancer or potentially harming human reproduction or the nervous system, as well as substances which are highly toxic to pollinators or which build up in drinking water and groundwater. Yet the exact same problematic substances are still authorised for use in many low- and middle-income countries. This can be because of inadequate legislation, undue industry influence or severe understaffing of regulatory authorities.

Catastrophic health consequences

The use of these highly toxic substances is particularly problematic in the Global South. Workers and smallholders are given little information about the health risks in many cases and apply pesticides without adequate personal protective equipment – either because it is impracticable because of the heat, unaffordable or simply not obtainable at all. Countless pesticide poisonings are the consequence. According to a recent study cited by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), up to 385 million people unintentionally poison themselves with pesticides each year, the overwhelming majority of cases involving farmers and farm workers in Southern countries. Symptoms range from headaches, nausea or skin lesions to severe organ damage.

Workers and smallholders often apply pesticides without adequate personal protective equipment. Photo: Atul Loke/ Panos

According to conservative estimates, every year, at least 11,000 cases of poisoning end in fatalities, and very high numbers are assumed to go unreported. Added to that, the World Health Organization (WHO) puts the annual number of suicide deaths by pesticide ingestion at over 160,000 – which is around a fifth of all suicides world-wide. At times these can be a tragic expression of an economic downward spiral which all too often takes hold of impoverished and usually uninsured small farmers. Many get into debt to buy expensive pesticides, fertilisers and seeds.

"Every year, at least 11,000 cases of pesticide poisoning end in fatalities."

Acute poisonings are not the only problem by far. Repeated and long-term exposure to pesticides is also linked to chronic diseases. Especially those classified as highly hazardous pesticides can have chronic effects on the “skin, eyes, nervous system, cardiovascular system, gastrointestinal tract, liver, kidneys, reproductive system, endocrine system, immune system and blood”, and some “may cause cancer, including childhood cancer”, the WHO notes. The UN organisation considers exposure to highly hazardous pesticides to be “a major public health concern”.

Crisis is being instrumentalised

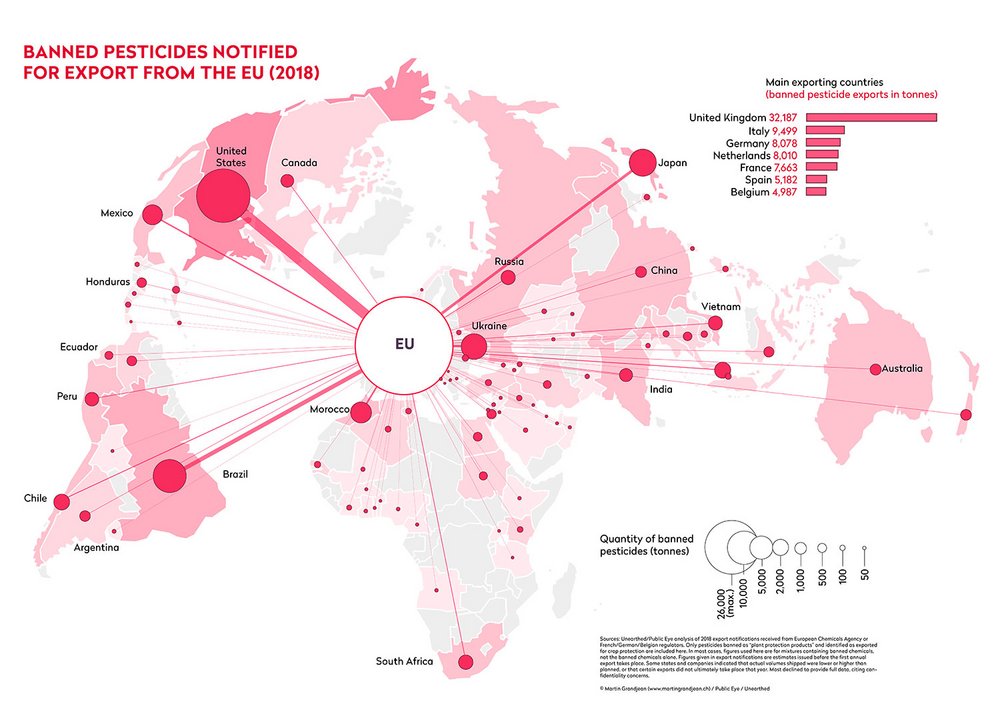

As our research has shown, Europe and the USA’s large pesticide corporations also play an important role in the global trade in highly hazardous pesticides – many of which are banned in the countries these corporations are based in. Despite the ban on their use in the EU, they are still produced in European factories and exported from there. We at the Swiss non-governmental organisation Public Eye worked with the British research organisation Unearthed to gather the first hard data on this trade in autumn 2020. Because the pesticide manufacturers maintain a wall of silence about their business, we invoked freedom of information laws to request the relevant “export notifications” from the European Chemicals Agency and EU Member States. According to these notifications from companies to the authorities, in the year 2018 alone, EU countries – most significantly Italy, Germany, the Netherlands and France as well as the UK – approved the export of 81,615 tonnes of pesticides that were banned from their own fields due to unacceptable health and environmental risks (see map).

The manufacturers dismiss any responsibility and take the position that provided they are used as instructed, substances prohibited in our own countries are harmless in the South. In the context of current crises like the war in Ukraine and the energy and food price crises precipitated in its wake, the top four have managed to boost their pesticide sales and profits. Not only that, but the industry also made use of the crises to lobby for chemical-intensive agriculture and against organic production methods by talking up the spectre of a looming food shortage. Syngenta CEO Erik Fyrwald launched an unprecedented attack on organic farming in summer 2022. “Food is being taken away from people in Africa because we want organic produce and our governments support organic farming,” was the quote Fyrwald gave to the media at the time.

While these claims caused a major furore, they were quickly debunked as groundless. It was found that the ongoing food crisis is not, for the most part, a supply crisis as enough food has been available at all times. It has actually been fuelled by factors such as sharply rising food, energy and living costs and by diverse political conflicts and wars, with devastating consequences for people living in food insecurity and hunger, whose numbers have been back on the rise since 2015.

The sudden spikes in fertiliser and pesticide prices coupled with the climate crisis also pose immense problems for farmers in the South. Against this backdrop, promoting more independent agro-ecological forms of production which conserve soils and biodiversity in the long term makes much more sense than intensifying agriculture with chemical inputs. But the pesticide industry continues to call for exactly that. Syngenta & Co. are pushing back hard against the EU strategy for more sustainable agriculture (“Farm to Fork”) and the associated pesticide reduction targets.

Is a turnaround on exports coming?

The pesticide lobby is also trying to prevent the EU from introducing an export ban on pesticides that are prohibited within its own borders. After Public Eye and Unearthed had drawn attention to these exports, the European Commission made a surprise announcement in October 2020 that it intended to stop the problematic practice. Prior to that, France had already become the first European country to impose such an export ban with effect from 2022, and Switzerland has had stricter export conditions in force since 2021. Germany and Belgium have also announced a halt to exports of pesticides banned in their own countries. These are important first steps. Nevertheless, as our latest research shows, the national bans in place to date have critical weak points. French authorities approved countless export applications for banned pesticides from January to September 2022 in spite of the ban. This was possible because of various loopholes in the French law, which only prohibits the export of “crop protection products” containing banned substances, but not the export of the active ingredients in their pure form. Another problem is that when single countries impose export bans, companies can simply circumvent them by relocating their production sites elsewhere.

Public Eye and more than 320 other NGOs and trade unions, including numerous organisations from the Global South, have therefore called upon the EU to swiftly implement an effective and comprehensive export ban. The EU had originally committed to presenting a legislative proposal for such a ban by 2023, but is taking a long time. The proposal is facing heavy opposition from the chemicals lobby. However, when the European Commission finally launched a public consultation in May, environment commissioner Virginijus Sinkevičius stressed that the EU “would not be consistent in its ambition for a toxic-free environment if hazardous chemicals that are not allowed for use in the EU can still be produced here and then exported”. These chemicals, he added, “can cause the same harm to health and the environment regardless of where they are being used”. It’s now high time for the EU to walk the talk.

Contact: carla.hoinkes(at)publiceye.ch

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment