The economics of biodiversity

Despite the pledge to halt the loss of biodiversity and ecosystem services, most countries have failed to achieve the 20 Aichi Biodiversity Targets (see "The Convention on Biological Diversity and the Aichi Targets") as stated in the UN’s Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020. Degradation of biodiversity and ecosystems has continued unabated, if not accelerated, during the last decade. The recent Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services conducted by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) notes that one million species are at risk of extinction during the coming decades. Out of 18 ecosystem services evaluated, except for agricultural, fish and bioenergy production and material harvest, all services reported negative trends between 1970 and 2019.

According to the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), each year, the world loses 6.3 trillion US dollars (USD) worth of ecological services due to forest and land degradation. An IPBES report notes that loss of pollinators threatens global crop output worth between 235 billion and 577 billion USD annually. Pollution is estimated to cause around 9 million premature deaths annually, and other environment-related health risks claim millions more each year. Land use and land cover change and climate change are among the major drivers contributing to loss of biodiversity and ecosystem services. If unchecked, this will have an adverse impact on economies, ecosystems, lives and livelihoods. It will also jeopardise achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Biodiversity provides several goods and services that are critical to human well-being and good quality of life. The genetic pool that it contains helps develop new crop varieties and drugs which are assuming relevance in combating the adverse effects of rapid environmental change. Nature can help reduce vulnerability to climate and health risks. A UN report estimated the direct economic losses due to disasters between 1998 and 2017 at 2.98 trillion USD (in 2017 USD), of which climate-related losses accounted for 78 per cent.

Economics – not only monetary terms count

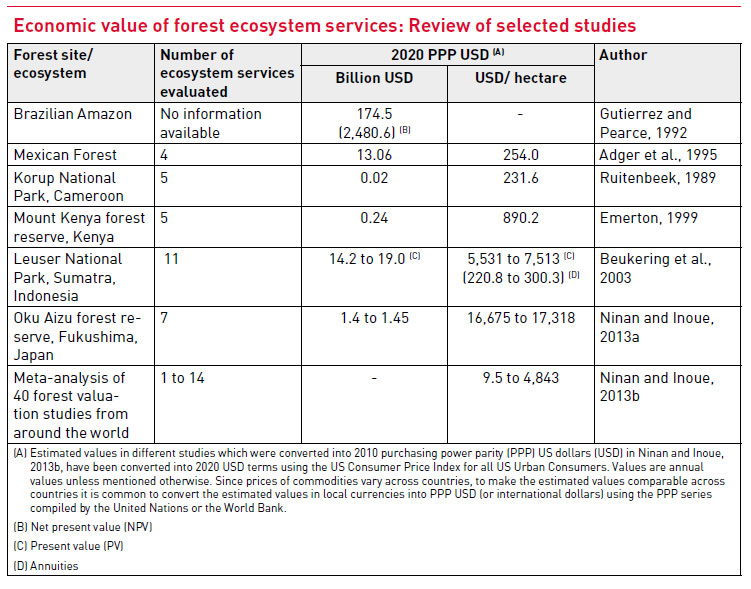

The economic benefits offered by biodiversity and ecosystem services are immense. For instance, the annual economic value of ecosystem services provided by forest ecosystems is worth billions of US dollars (see Table). Estimated economic values are however sensitive to the methods, norms and prices used to value ecosystem services, as well as the number of ecosystem services evaluated. There are other values of nature (e.g. relational values referring to the quality of human-nature interactions) which cannot be expressed in monetary terms. Experts therefore advocate the use of plural approaches to assess the diverse values of nature. Economic valuation is however useful since it speaks in the language easily understood by policy-makers. Besides, it underlines the point that just because an ecosystem service is not traded in a market or difficult to value, it need not be a zero-priced good or have no value. Merely that oxygen – the provision of which is a life-giving service – is freely available in the atmosphere does not mean that it has no economic value. The raging second COVID-19 wave in India has helped to gauge the true economic value of oxygen with COVID-19-stricken patients desperately trying to purchase oxygen cylinders or the Indian government and other agencies making emergency purchases or imports of oxygen tanks, concentrators and cylinders.

Human well-being and SDGs

Apart from providing multiple benefits to people, in terms of biodiversity and ecosystem services, nature helps reduce vulnerability to climate-related disasters and extreme weather events as well as health risks. It plays an important role in influencing human well-being and good quality of life. Two of the SDGs, SDG 14 and SDG 15 (Life below Water and Life on Land), relate to marine and terrestrial ecosystems covering biodiversity and ecosystem services. Most of the 17 SDGs refer directly or indirectly to nature, addressing poverty, hunger, health, water, sanitation, etc. Missing the 20 Aichi Biodiversity Targets already imperils achievement of the SDGs, which is further jeopardised by the COVID-19 pandemic. While framing the post-2020 biodiversity targets, there is a need to align them such that they fit in with the metrics tracked by the SDGs.

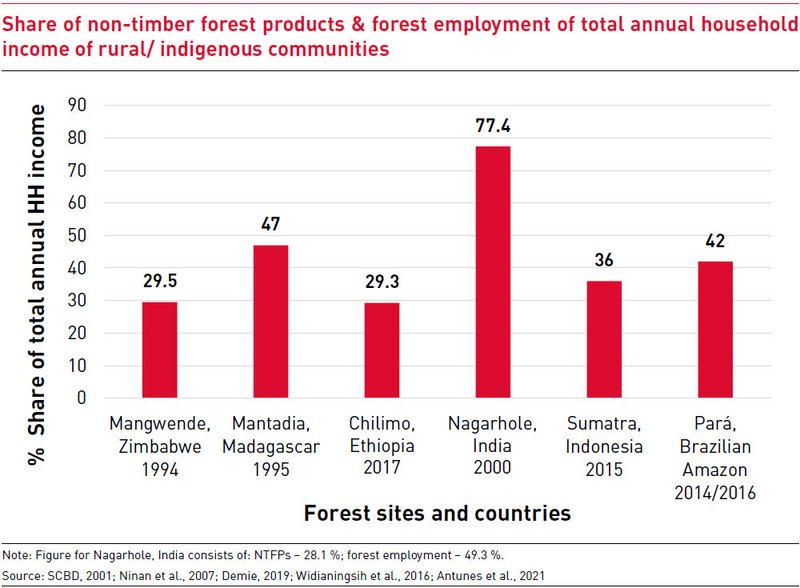

Nature-based activities contribute a significant share to the incomes and well-being of many nations especially developing countries, and of poor and indigenous communities. The report by the World Economic Forum (WEF) on Nature Risks Rising notes that some of the fastest growing economies of the world are highly vulnerable to nature loss. For example, about a third of the gross domestic product (GDP) in India and Indonesia is generated in nature-dependent sectors. African countries reported this share to be 23 per cent of their GDP. Even large economies such as China, the EU and the USA, which together account for 60 per cent of global GDP, reported high amounts of GDP as being generated in nature-dependent sectors, i.e. 2.7 trillion USD in China, 2.4 trillion USD in the EU and 2.1 trillion USD in the USA. Poor and indigenous communities rely on the natural environment for subsistence, income, and employment. Non-timber forest products (NTFPs) and forest employment contribute a significant share to their household income (see Figure).

The WEF report analysed 163 industries and their supply chains and found that about 44 trillion USD of economic value generation – over half of the world’s GDP – is highly dependent on nature and its services. Sectors here include construction, agriculture, food and beverages, with an economic value of 7.9 trillion USD – roughly twice the size of Germany’s economy (about 4 trillion USD). The pharmaceutical industry depends on tropical rainforests and plants for many existing and potential drugs. For instance, 25 per cent of drugs used in modern medicine are derived from rainforest plants. About 50 per cent of prescription drugs are based on molecules coming from plants.

Benefits of nature-based solutions

Nature-based solutions (NBS – see Box) are being advocated to reduce vulnerability to the risks posed by climate change, environmental degradation and zoonotic diseases. NBS are cost-effective and can help promote multiple objectives such as climate stabilisation, conservation and development. They have co-benefits such as generating job opportunities and enhancing biodiversity, and are critical for realising the SDGs.

NATURE-BASED SOLUTIONS (NBS)

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) defines NBS as “actions to protect, sustainably manage, and restore natural or modified ecosystems, that address societal challenges effectively and adaptively, simultaneously providing human well-being and biodiversity benefits”, with climate change, food security, disaster risks, water security, social and economic development as well as human health being the common societal challenges.

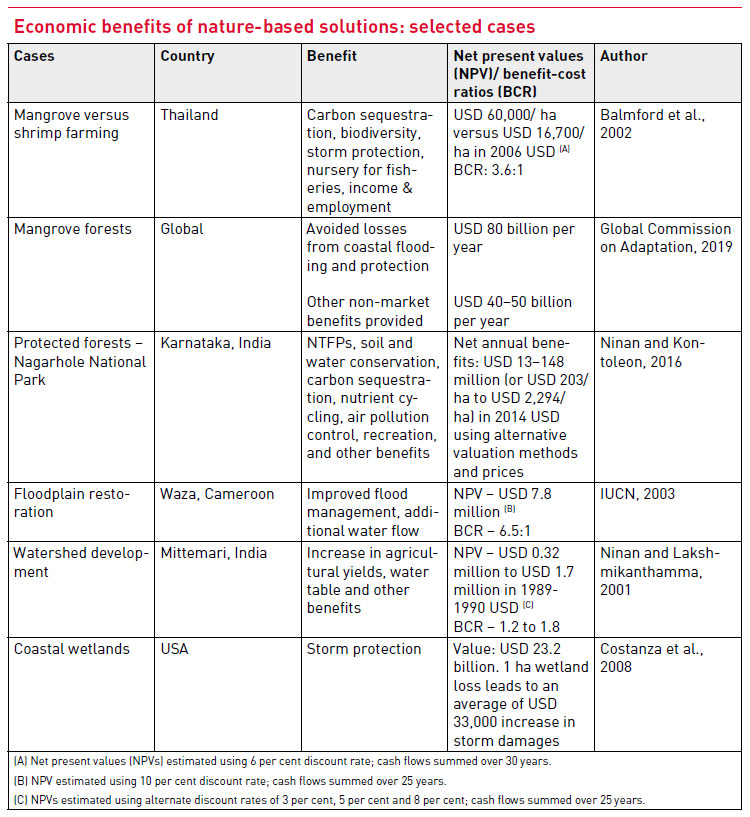

The economic benefits of NBS are significant. The conservation of mangroves, protected areas, floodplains and watersheds yields high benefits, including non-market benefits such as carbon sequestration, soil and water conservation as well as flood management and storm protection services (see Table below). For instance, a study in Thailand estimated the net benefits from conserving mangroves to be 3.6 times higher than from shrimp farming. Another study noted the avoided losses from coastal flooding and other non-market benefits from mangrove forests valued at 120-130 billion USD per year globally. A study of floodplain restoration in Waza, Cameroon, established a 6.5:1 benefit-cost ratio (BCR) with improved flood management and water flow benefits. The Rewilding Europe project has reported encouraging results with recovery of ecosystem health, species and co-benefits such as an increase in tourist visitation rates. A UN report notes that restoring 350 million hectares of degraded landscapes globally by 2030, as envisaged in the Bonn Challenge, would yield benefits worth 9 trillion USD for an investment of 1 trillion USD (about 0.1 per cent of global GDP between 2021 and 2030), remove an additional 13–26 gigatons from the atmosphere and contribute to poverty alleviation. NBS could also form part of COVID-19-recovery stimulus programmes.

How to enhance biodiversity and economic prosperity – key messages of the Dasgupta Biodiversity Review

The COP15 meeting of the UN’s Convention on Biological Diversity in Kunming, China, from the 11th to the 24th October 2021, is expected to finalise the post-2020 global biodiversity conservation framework for a future where humankind lives in harmony with nature. In this context, it is worth looking at the key messages of a review commissioned by the UK Government headed by Sir Partha Dasgupta to assess the economic value of biodiversity and to identify actions that will simultaneously enhance biodiversity and economic prosperity. The review calls for a paradigm shift in the way we think, act and measure economic success and to protect and enhance our prosperity and the natural world. It calls for institutional, market, financial and educational reforms to improve the outcomes for nature. The review’s key messages include the following:

- The way in which governments assess pro-gress or well-being in terms of GDP has to change. GDP is a flawed measure since it ignores how environmental degradation or income distribution impact long-term well-being. For example, a barrel of oil or a tonne of iron ore extracted today is counted as an addition to GDP. Being non-renewable, these resources once extracted are no longer available for future generations and hence will constrain long-term economic growth and welfare. Traditional national income accounts consider depreciation of anthropogenic capital, but not of natural capital, even though its depletion will affect long-term well-being and sustainable development. The review argues that to accurately measure well-being, one ought to consider the concept of inclusive wealth, which covers produced capital (factories, machines and roads), human capital (skills and knowledge) and natural capital (e.g. soils, forests and lakes). Tracking the changes in these three forms of assets will better capture social well-being. UNEP’s Inclusive Wealth Report 2018 compared the per capita GDP (income) growth in 140 countries with per capita (inclusive) wealth and noted that 44 out of 140 countries reported a decline in per capita (inclusive) wealth between 1990 and 2014, even though per capita GDP increased in most countries. However, like GDP, the inclusive wealth index (IWI) also has shortcomings in that it does not tell us anything about income (or wealth) distribution within countries, which affects well-being.

- The coverage and investments in protected areas (PAs) need to be increased both on the land and in the seas. According to the report, to protect 30 per cent of the world’s land and oceans and manage them effectively by 2030 would require an average investment of 140 billion USD annually, which is just about 0.16 per cent of global GDP and less than a third of the current global subsidies supporting activities that destroy nature. The benefits from this would be immense and include lowering climate and health risks. Let alone increasing the coverage of PAs, the report notes that only 20 per cent of existing PAs are managed well. It calls for greater involvement of indigenous people and local communities in their management. Maintaining our current living standards would require 1.6 Earths, which is unsustainable. The review calls for a shift towards a sustainable food production system, decarbonising our energy and transport systems, reordering our consumption and production patterns, and reducing food wastages estimated at a third of global food production to lower our carbon footprint. Further, it emphasises the need to reduce perverse subsidies (globally estimated at 4–6 trillion USD annually) that favour destruction of nature. It calls for increased financial flows and implementation of Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) schemes and Debt for Nature swaps to reward those countries and communities who conserve and supply ecosystem services.

- Businesses and financial institutions are increasingly concerned about nature-related financial risks and their impact on their production and revenues. They therefore need to incorporate sustainability concerns to hedge their businesses and institutions from these risks. The report calls for an increase in green investments and nature-based solutions to address the nature-related risks faced by businesses, financial institutions, and economies.

- To connect people with nature, the review calls for reforming our educational system, whereby studying natural history is made part of the curriculum from the early stages. Ultimately, all citizens should in part be naturalists. The review calls for empowering citizens to ensure better outcomes for nature.

Unless there is a transformative change in the way that governments and societies perceive the value and role of nature to promote human well-being and sustainable development prospects for biodiversity and humankind will remain grim. If you take care of nature, nature will take care of you. If you abuse nature, nature too will abuse you. In the words of Mahatma Gandhi: “Earth provides enough to satisfy every man’s needs, but not every man’s greed.”

K. N. Ninan is Senior Fellow at the World Resources Institute (WRI) India, New Delhi, and Lead Author, Working Group III Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Geneva, Switzerland. Prior to this, he was Professor of Ecological Economics at the Institute for Social and Economic Change in Bangalore, India, and Co-Chair, Methodological Assessment of Scenarios and Models of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services at the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services in Bonn, Germany.

Contact: ninankn@yahoo.co.in

References

Adgers, W.N., Brown, K., Cervigni, R. and Moran, D. (1995). Total economic value of forests in Mexico, Ambio,24 (5), 286-296. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4314349

Balmford A, Bruner A, Cooper P, Costanza R et al. (2002). Economic reasons for conserving wild nature, Science, 297 (5583), 950-953. DOI: 10.1126/science.1073947

Beukering, P.H., van Cesar, H.S.J., Janssen, M.A. (2003). Economic valuation of the Leuser National Park in Sumatra, Indonesia, Ecological Economics, 44, 43-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-8009(02)00224-0

Costanza R, Péérez-Maqueo O, Martinez M L, Sutton P, Anderson S J, Mulder K (2008). The value of coastal wetlands for hurricane protection, Ambio, 37 (4), 241-248. https://doi.org/10.1579/0044-7447(2008)37[241:TVOCWF]2.0.CO;2

CRED and UNISDR (2018). Economics Losses, Poverty and Disasters: 1998 to 2017. Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED) and United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNISDR), Geneva, Switzerland. https://www.unisdr.org/files/61119_credeconomiclosses.pdf

Demie, G. (2019). Contribution of Non-Timber Forest Products in Rural Communities’ Livelihoods around Chilimo Forest, West Shewa, Ethiopia, Journal of Natural Sciences Research, 9 (22), 25-37.

Emerton, L. (1999). Mount Kenya: The economics of community conservation, Evaluating Eden Discussion Paper 4, September, International Institute for Environment and Development, London, UK. https://pubs.iied.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/migrate/7797IIED.pdf

Fernandez, N., Torres, N., Wolf, F., Quintero, L., Pereira, H.M. (2020). Ecological Restoration for a Wilder Europe. https://dx.doi.org/10.978.39817938/57

Gutierrez, B., Pearce, D.W. (1992). Estimating the environmental benefits of the Amazon forest: an inter-temporal valuation exercise, GEC Working Paper 92-44, CSERGE, University College London and University of East Anglia, U.K.

Global Commission on Adaptation (2019). Adapt Now: A Global Call for Leadership on Climate Resilience, Global Centre on Adaptation and World Resources Institute, September. https://gca.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/GlobalCommission_Report_FINAL.pdf

IUCN (2003). Waza Logone Floodplain: Economic benefits of wetland restoration, Case Studies in Valuation of Wetlands No.4, May, IUCN, Switzerland. https://www.cbd.int/financial/values/cameroon-valuewaza.pdf

Ninan, K. N., Lakshmikanthamma, S. (2001). Social-Cost benefit analysis of a watershed development project in Karnataka, India, Ambio, 30 (3), 157-161. https://doi.org/10.1579/0044-7447-30.3.157

Ninan, K.N., Satyapalan, J., Babu, P., Ramkrishnappa, V. (2007). The Economics of Biodiversity Conservation-Valuation in Tropical Forest Ecosystems, Earthscan, London and Washington. 264 p.

Ninan K N, Inoue M. (2013a). Valuing forest ecosystem services: case study of a forest reserve in Japan. Ecosystem Services, 5, e78-e87. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2013.02.006

Ninan, K.N., Inoue, M. (2013b). Valuing forest ecosystem services: what we know and what we don’t, Ecological Economics, 93, 137-149, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2013.05.005

Ninan, K.N. (ed.) (2014). Valuing Ecosystem Services-Methodological Issues and Case Studies, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, U.K. and Northampton, U.S.A. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781781955161

Ninan K. N., Kontoleon, A. (2016). Valuing forest ecosystem services and disservices: case study of a protected area in India, Ecosystem Services, 20, 1-14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016.j.ecoser.2016.05-001

Pascual, U., Balvanera, P., Díaz, S. et al (2017). Valuing nature’s contribution to people: the IPBES approach, Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 26-27, 7-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2016.12.006

Pearce, D., Moran, D., (1994). The Economic Value of Biodiversity. Earthscan, London. https://www.cbd.int/financial/values/g-economicvalue-iucn.pdf

Ruitenbeek, H.J. (1989). Social cost benefit analysis of the Korup project, Cameroon, WWF Report. World Wildlife Fund, London, U.K.

SCBD (2001). The Value of Forest Ecosystems, CBD Technical Series No.4, Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, Montreal, Canada. https://www.cbd.int/doc/publications/cbd-ts-04.pdf

UNEP (2018). Inclusive Wealth Report 2018, (eds), S. Managi and P.Kumar. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi. https://www.unep.org/resources/report/inclusive-wealth-report-2018

UNEP (2020). UN Decade of Ecosystem Restoration, UNEP, Nairobi. https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/press-release/new-un-decade-ecosystem-restoration-offers-unparalleled-opportunity

WEF (2020). Nature Risks Rising: Why the Crisis Engulfing Nature Matters for Business and the Economy, World Economic Forum, Geneva, Switzerland. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_New_Nature_Economy_Report_2020.pdf

Widianingsih, N.N., Theilad, I., Pouliet, M. (2016). Contribution of forest restoration to rural livelihoods and household income in Indonesia, Sustainability, 8 (9), 835. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8090835

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment