Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

The cost of high food prices in West Africa

The 2007-08 world food price crisis caused political turmoil and social unrest in many West African countries. Poor urban households, in particular, were unable to afford food and demonstrated vocally in cities such as Dakar and Abidjan. Price is a key determinant of a household’s access to food. As the region urbanises rapidly, more and more consumers are becoming dependent on markets for food. Yet structural changes in demand are driving food prices upward, independent of the global context. Food demand has increased fivefold over the past 60 years and dietary patterns have also transformed considerably. Consumers are increasingly looking for foods that are convenient to buy, prepare and consume; 39 per cent of all food consumed in West Africa today is processed. West African supply is adjusting to these growing and diversifying consumption patterns, but at a slower rate than demand. This is affecting market conditions and resulting in higher prices.

Getting prices right

Prices have mixed effects on the welfare of households. On the one hand, increased prices mean improved incomes for producers, whilst on the other, they translate into higher food costs for consumers. The net effect depends on the structure of the economy and on the share of household food consumption that is supplied by markets. In predominantly agricultural countries, the majority of households might be better off with higher food prices. However, the rapid urbanisation taking place in West Africa calls into question certain assumptions as to what the “right” level of food prices should be.

A higher share and growing number of West African households are now dependent on non-agricultural activities for their living. This includes most urban households, which account for 45 per cent of the region’s total population. It also comprises many living in rural areas where an estimated 25 per cent of households are engaged primarily in non-agricultural activities. As a result, a growing number and share of consumers rely on markets for their food supply. Overall, markets now provide at least two-thirds of household food supply as West Africans become buyers – rather than producers – of food and spend a larger share of their food budget at markets. This growing number of households would stand to lose from any increase in prices. These same households are also highly sensitive to fluctuations in prices as food represents 50 per cent of their total budget. It is therefore time for policy-makers to get food prices right, both for the welfare of households and food security.

A costly Africa

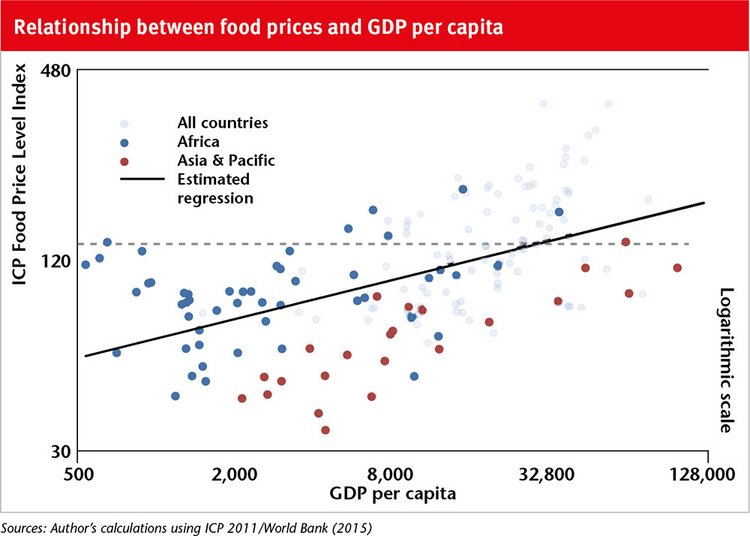

Are food prices currently too high in West Africa? Using data from the 2011 International Comparison Program (ICP), we estimate that food prices in sub-Saharan Africa are 30 to 40 per cent above prices in other areas of the world with comparable levels of development. The Figure below illustrates the relationship between food price levels and GDP per capita. It shows that the majority of African countries are above the line, indicating a higher level of food prices relative to other countries at a similar level of development. This corresponds with research by Gelb et al. (2013) who found that overall price levels in sub-Saharan African countries are 35 per cent higher when compared to their predicted values. In addition, food is particularly expensive compared to non-food products. In West Africa, food prices are 50 to 130 per cent above the overall price level index, indicating that food is more expensive in real terms than non-food products. These higher food prices translate into a welfare loss for households.

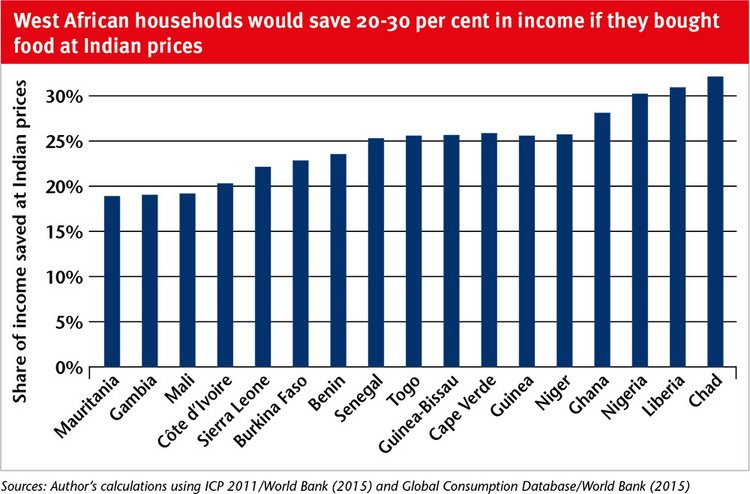

A comparison with India reveals a vivid picture of how high food prices impact the purchasing power of Africans. Using food price differentials between West African countries and India, as well as looking at expenditure shares, it is possible to provide a rough estimate of how much a typical West African food basket would cost in India. The resulting comparison shows that households could save from 20 per cent of their income in countries such as Côte d’Ivoire, the Gambia and Mauritania, to approximately 30 per cent in Chad and Liberia (see Figure). These results provide an indication of the degree of household welfare loss resulting from the price gap reported between India and West Africa. It confirms that West African households are strongly impacted by the high prices stemming from the West African food system. It also provides an explanation for the trend in increased food imports.

What should policy-makers do?

Driven by population growth, urbanisation and income growth, West Africa’s food system is changing. Consumers are also changing their habits, adding more variety to their diets, turning towards processed foods that are convenient to prepare and consume, and attaching greater value to other product attributes such as quality, healthfulness and packaging. This shift in consumer habits will necessarily drive the demand for increased post-harvest activities in food production. The design of food policies should take these changes into consideration as well as strive to balance the needs of consumers and producers.

A look at price levels by food group can provide interesting insight into policy options. To begin with, there is a clear hierarchy of prices across all countries in the region, in that dairy and fats/oil products are always the most expensive foods while fish, cereals, fruits and vegetables are the least expensive. Processed foods are more expensive in absolute terms than in the United States for many West African countries, yet they are increasingly in demand. Cereals remain an important contributor to a household’s overall food budget, but focusing on cereals is no longer the only strategy for easing household budget constraints. For instance, countries like Côte d’Ivoire, the Gambia, Ghana, Nigeria and Togo should also be addressing the challenges and constraints that hinder the development of fruit and vegetable value chains. In Ghana, we estimate that a one per cent decrease in cereal prices would lead to a 0.19 per cent decrease in overall food prices, whilst a decrease of the same amount in the price of fruits and vegetables would have a larger impact, leading to a decrease of 0.35 per cent. These previously “forgotten” food sectors will provide local products and jobs for a growing market of domestic consumers.

Unlocking the intraregional trade potential of West Africa and expanding its food market is a priority challenge. The relatively high food price differential across the region – from -28 per cent in Mauritania to +14 per cent in Ghana relative to the regional average – indicates the relative inefficiency of the regional food market, which allows price transmission but with significant transaction costs. Public actions should focus on improving physical infrastructure, enhancing customs efficiency, and developing and enforcing necessary regulatory mechanisms. These initiatives will all contribute to lowering transport costs and ultimately food prices. A more comprehensive trade corridor approach could provide the framework to overcome the investment and institutional challenges, and to facilitate regional trade.

Increasing productivity is at the heart of the solution to limit increases in price. Long-term food supply will be determined by the amount of productive resources available for production as well as the productivity of these resources. Raising productivity will have substantial impacts on prices and on farmers’ incomes, eventually decreasing rural poverty and making food more affordable for the urban poor. Many productivity-increasing solutions are within the West African farmer’s reach. Yet more – and better – investments in the agro-food sector are increasingly required to respond to new and growing demand. This will happen if the business case for investing in increased productivity in the agro-food sector can be effectively demonstrated. Both public and private-sector stakeholders need to be involved in the process, while investment assistance from abroad will be instrumental.

Thomas Allen

Sahel and West Africa Club Secretariat

OECD – Organisation for Economic

Co-operation and Development

Paris, France

Thomas.Allen@oecd.org

References and further reading

- Allen, T. and P. Heinrigs (2016), “Emerging Opportunities in the West African Food Economy”, West African Papers, No. 1, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jlvfj4968jb-en

- Gelb, A., C. J. Meyer and V. Ramachandran (2013), “Does poor mean cheap? A comparative look at Africa's industrial labor costs”, working paper, No. 325, Center for Global Development.

- Moriconi-Ebrard, F., D. Harre and P. Heinrigs (2016), Urbanisation Dynamics in West Africa 1950–2010: Africapolis I, 2015 Update, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264252233-en

- OECD/SWAC (2013), Settlement, Market and Food Security, OECD Publishing, Paris http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264187443-en

- Staatz, J. and F. Hollinger (2016), “West African Food Systems and Changing Consumer Demands”, West African Papers, No. 4, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/b165522b-en

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment