- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

People suffer as rivers rage and recede amid deepening climate crisis

As they worked in their mustard farm in Sail, a beautiful hamlet in southern Kashmir in the Indian Himalayas, Zahid Iqbal, a young farmer and his wife hoped that their farm wouldn’t get inundated by floods again. “We lost the previous crop to flooding,” said 36-year-old Iqbal.

“Last spring, flooding in the stream flanking our farm destroyed our crop,” he explained while the couple gave final touches to the soil for a fresh crop. “We hope for a good spring — and a good crop,” Iqbal aspired as he began sowing the seeds by scattering them systematically on the prepared soil.

He said that yields from the mustard crop fetch the family around INR 35,000 (USD 443) annually besides edible oil for consumption at home. The losses from the previous crop failure denied Iqbal the extra earnings and the oil for at home from his field.

Farmer Zahid Iqbal and his wife working in their farm in Sail Village in southern Kashmir.

Photo: ©Athar Parvaiz

The farmers in Sail have a limited choice. “If our land was suited for apple trees, we would have happily converted it into apple orchards,” said Bilal Ahmad, whose farm borders Iqbal’s farm. “But, it is not. So, we have no choice but to live with the flood threats.”

Three elderly farmers who sat languidly on a shop-front in the village said that they were mystified by the uncanny increase in floods. “Not that floods wouldn’t occur in our times … those days, they weren’t so frequent” said 70-year-old Ghulam Mohammad Shah.

Floods and droughts by turns

In other parts of Kashmir, floods and water shortages happen by turns. In the past seven years, officials in the region announced flood threats thrice in three different years and advised farmers in 2018 and 2022 not to cultivate rice paddies because of water scarcity.

“Please don’t go for paddy cultivation this year as we won’t be able to supply any water for irrigation,” read notices issued to the farmers in local language by the Irrigation and Flood Control (IFC) Department. People across Kashmir have also become used to hearing about the flood alerts around the River Jhelum, the main river flowing through Kashmir.

The latest flood alert was announced by the IFC Department this June: “The Flood Declaration mark of 18 feet at Ram Munshibagh has been touched. (People) residing along the River Jhelum in South/Central/North Kashmir are requested to remain vigilant.”

Farhat Shaheen an associate professor at Sher-e-Kashmir University of Agricultural Sciences and Technology (SKUAST) who studies agro-economy and impacts of climate change on crops, said that frequent spells of drought during recent years in Kashmir Himalayas “is resulting in losses for people dependent on agriculture besides impacting the environment”. “Jhelum basin in Kashmir is more prone to floods rather than droughts,” Shaheen further noted. “But droughts of severe and moderate intensity were witnessed five times in the past seven years in the basin, with the water level in the River Jhelum in 2017 recorded the worst ever in 61 years.”

In Chendargund, a tiny village in the foothills of the stunning Pir Panjal mountain range, villagers said that the stream (Afzaer) flowing through their village “has broken our back (Qamar Chun Futromout)”, an idiomatic expression in local language for a painful experience.

“It has destroyed our farms and has washed away the road which connected us to the main road. A few months back my husband fell sick, and my son had to carry him on his back up to the main road where we put him in the car and took him to the hospital,” recalled 55-year-old Saleema Begam.

“And look at this trickle in the stream. It is so dirty. If there was more water in the stream, it wouldn’t look so dirty,” Begam said. “Unfortunately, we have no option but to use this dirty water for washing dishes.”

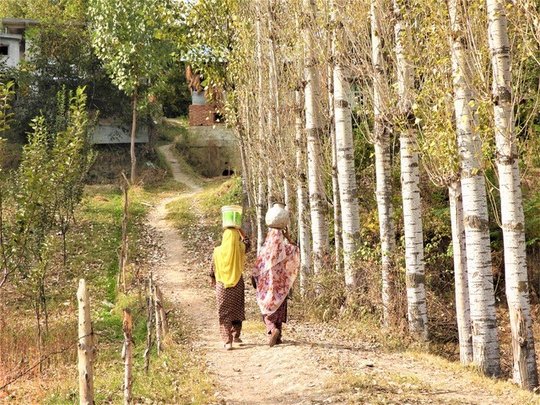

Women carry water in the Chendargund village in western part of Kashmir.

Photo: ©Athar Parvaiz

Glaciers are vanishing in Himalayas and Alps alike

Citing data from their team’s latest field survey of the seven glaciers they have been monitoring annually in Indian Himalayas, Kashmiri glaciologists reported that the surveyed glaciers had suddenly shrunk by an average five metres as compared to the annual average shrinkage of one metre per year in the past six years.

“Our observations of the melting of seven glaciers in the Jammu, Kashmir, and Ladakh Himalaya this year showed unprecedented glacier melting because the year is abnormal from a climatic perspective,” said Shakil Ahmad Romshoo, a senior glaciologist who heads Kashmir University’s Earth Sciences Department.

Referring to a recent revelation about the Alps by scientists that glaciers had been vanishing at a record rate in that region following heat waves, Romshoo explained that climate change was not limited to the Alps alone. “Himalayas are equally affected,” he said.

“In fact, the Indian Himalayan glaciers are melting as a result of both climate change and air pollution. This year, we saw extraordinary glacier melting in Jammu, Kashmir and Ladakh,” he reported, adding that this would have a significant influence on the region’s food, water and energy security.

Regarding the stream flows, Romshoo said: “The decrease in snow precipitation and increase in rainfall during the winter and early spring months, particularly at higher attitudes, together with the early melting of the accumulated snowpack in response to the increased temperatures result in an early and rapid runoff peak in the Jhelum basin.”

He further noted: “It has been reported in published research that glaciers initially contribute increasingly to the stream-flow, under the increasing temperature, for a short period of time, followed by the decrease in stream-flow as the glacier mass depletion reaches the tipping point.” According to him, rapid melting of the glaciers contributes to the stream-flow around spring, not throughout the year.

Happening globally

The destructive impacts of the climate crisis are being felt around the world, said a UNEP brief on October 12th, ahead of the International Day for Disaster Risk Reduction.

“This year, unprecedented floods have left one-third of Pakistan underwater, people and animals are dying from climate-related droughts in East Africa, and China is experiencing the most severe heat wave ever recorded,” the brief said, urging the world leaders to invest as much in adaptation as they do in mitigation because without adaptation economies, food security and global stability are under threat.

In its October 2022 report, the CDP (Carbon Disclosure Project), a global non-profit, revealed that four in five cities (80%) in the world were now reporting that they were facing significant climate hazards in 2022, such as extreme heat (46%), heavy rainfall (36%), drought (35%) and urban flooding (33%). At the same time, almost two thirds of cities (64%) were already experiencing significant impacts from climate hazards, the report said.

The report further said that the risk to people’s livelihoods — their economic situation, job security and access to resources — was also increasing with the threat the warming planet poses to economies and societies the world over. In 2022, the report said, almost three in four cities (72%) had identified critical resources at risk from climate hazards, such as water supply (46% of cities), agriculture (43%), sewerage and waste management (41%), transportation (33%), and electricity and gas (32%).

Athar Parvaiz is a freelance journalist based in Srinagar/ Kashmir, India

More information:

CDP October 2022 report

UNEP brief

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment