- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Mechanisation of African agriculture – job creator or job killer?

Seventy per cent of Africa’s population are employed in agriculture, although they only supply 20 per cent of the continent’s net product. At the same time, an estimated 750 million Africans will be under the age of 18 years by 2030. These young people need job prospects. Here, the agricultural and food sector holds a big potential – provided that it can become more productive, and hence more attractive, for example through mechanisation. But doesn’t mechanisation tend to be more of a job killer than a job creator? Along with other preconditions for successful mechanisation, this was a topic discussed by representatives from science, business and development co-operation at the invitation of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) and the Malabo Montpellier Panel in Berlin, Germany, in late February 2018.

Success factors

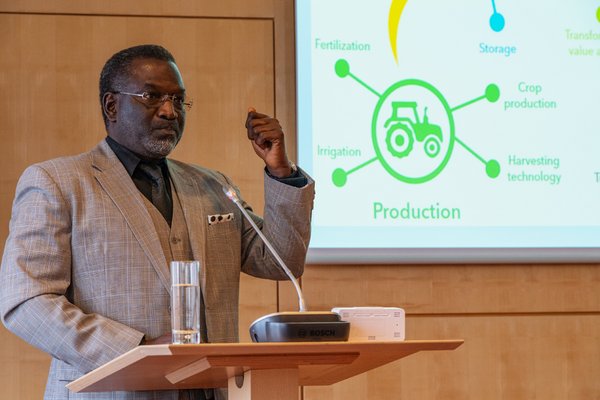

Ousmane Badiane, Director for Africa at the International Food Policy Research Centre (IFPRI) and Co-Chair of the Malabo-Montpellier Panel, presented the results of a study conducted by the Panel on the state of mechanisation in Africa. Using Ethiopia, Morocco, Malawi, Mali, Rwanda, Tanzania and Zambia as examples of countries that have shown a strong growth in both mechanisation and agricultural output, Badiane demonstrated success factors for mechanisation. Apparently, interventions were successful wherever dedicated government programmes and public private partnerships as well as hiring services were available, banking services were there to co-operate with, attention was given to downstream value chains, and research & development as well as skills development/training played an important role. In contrast, mechanisation programmes always failed where the government had taken the lead and simply distributed machinery.

Practical experience

These insights were confirmed by practitioners attending the meeting. “If I just supply a tractor to a farmer, I haven’t really achieved much,” said Frank Nordmann, General Sales Manager Africa at Grimme Landmaschinenfabrik. Nordmann referred to a survey showing that the average life of tractors in Africa was at a mere eight months. Local training and the availability of spare parts were key factors to ensure the maintenance of equipment and hence the sustainability of mechanisation. “I believe that we have already achieved quite a lot in terms of training. But nothing will happen locally if I haven’t got any financing,” said Franz-Georg von Busse, Managing Director of farming machinery producers Lemken. According to Gisbert Dreyer of the Dreyer Foundation, interest rates of between 12 and 18 per cent, which were common among banks in West Africa, rendered mechanisation illusionary for smallholders. “We have to create a situation in which the farmer no longer requires capital or fixed costs are low,” said Badiane. This could be accomplished by joining farming machinery co-operatives, but above all through hiring tractors, with digital solutions also playing an increasingly important role.

Listening to the target group

One example of this is the Hello Tractor firm, founded in 2016. Company founder Jehiel Oliver has developed a platform linking up tractor owners and farmers via an internet of things solution. This clusters demand, so that the machinery can be better utilised and using it is also worthwhile for owners in smallholder systems. Two things are crucial for young entrepreneur Oliver: that tractors are not subsidised and that technology is adapted to clients’ needs. “You can start at research level, but very quickly, you have to listen to your customers,” Oliver noted, referring to his experience with Hello Tractor.

“We are co-operating with ten million smallholder families in 39 countries. Almost every one of these families has innovations. But what we cannot manage is to transfer them and make them accessible to others,” said Jochen Moninger, Innovation Manager at Welthungerhilfe, stressing the importance of networking. However, here in the Global North, it was often difficult to enter talks with farming machinery companies. Considerable reservations still prevailed on both sides – the private sector and the NGOs. Moninger maintained that in this area, things had worked out well with small start-ups.

The issue of employment

Participants discussed how mechanisation impacts on jobs controversially. Theo Rauch, a professor at Berlin Free University/Germany, drew attention to women. If they participate in mechanisation and their workload is reduced, this does of course represent an advantage. However, Rauch maintained that there were enough examples of women farm labourers being made redundant by mechanisation. “If we don’t wish to aggravate the migration situation, we have to look very carefully at what we are doing,” Rauch noted.

Joachim von Braun, Director of the Center for Development Research (ZEF) at Bonn University/Germany and Co-Chair of the Malabo Montpellier Panel, recommended taking a macroeconomic view. If mechanisation helps farmers create more income, this will be spent on consumer goods and services, mainly at local level, which in turn creates jobs in local businesses. Employment is also generated in vocational training, e.g. through the training of vocational education teachers, as well as through setting up small rental services for machinery in rural areas.

A roundtable for mechanisation

The participants agreed that mechanisation could only work with the entire value chain, and that moreover, there was a greater need for organisational and political innovations than for technological solutions. Furthermore, the aim could not be to mechanise from the outside. Africa needed a farming machinery industry of its own. “I regard applying German mechanical engineering knowhow together with the right partners as a huge opportunity,” von Braun said, addressing the ministry. He suggested that a roundtable be set up with creative mechanical engineering firms from Germany and Africa.

Silvia Richter, editor, Rural 21

More information:

Download Report "Mechanized. Transforming Africa's Agriculture Value Chains"

Add a comment

Comments :