Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Traditional knowledge and intellectual property

Intellectual property generally refers to the creations of the human mind. These vary widely in their forms and expressions, ranging from inventions, designs and literary works to music, dances and movies.

Intellectual property is protected by legal rights, such as copyrights and related rights, patents, trademarks, industrial designs and trade secrets. Their scope and the specificity of protection vary. What most of them have in common is that their protection is limited in time (with some exceptions) and often requires application or registration, they are required to have an identifiable author or authors, and they are meant to protect new creations. Also, these rights are territorial, meaning that their protection is granted within a country under its national law. Regional or international protection in line with regional frameworks and international treaties is also possible. The protection of intellectual property rights supports and encourages the creative endeavours and innovative solutions of individuals, groups and enterprises, which in the end leads humanity to economic, socio-cultural, scientific and industrial growth.

Traditional knowledge, traditional cultural expressions and genetic resources

While, as yet, there is no accepted international definition of traditional knowledge (TK), the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) refers to TK as a living body of knowledge that is developed, sustained and passed down from generation to generation within a community, often forming part of its cultural or spiritual identity. Traditional cultural expressions (TCEs) are referred to forms in which TK and culture are expressed. As an example, a traditional weaving technique is TK, while the fabric created using that technique or traditional ornaments on it are TCEs. Importantly, “traditional” is not equal to “old” or “outdated”, as both TK and TCEs are constantly developing and being recreated within a community, as a response to the changing world.

WIPO often distinguishes between TK and TCEs because a different set of intellectual property rights may apply to their protection. For example, trademark and copyright protection may relate to some types of TCEs, while some TK may be protected under the laws that govern the protection of confidential information. Still, TK and TCEs share many similar characteristics, and sometimes, the TK abbreviation is used as a reference to both TK and TCEs.

Regarding genetic resources (GRs), Article 2 of the Convention on Biological Diversity defines them as “genetic material of actual or potential value”, and its definition of “genetic material” is “any material of plant, microbial or other origin containing functional units of heredity”. GRs-based innovations in the modern sciences are often protected under the intellectual property system, especially by patent laws. Some TK associated with GRs derive from Indigenous Peoples, and they often raise questions about the protection of such knowledge. This may for example apply to TK relating to the use of medical plants.

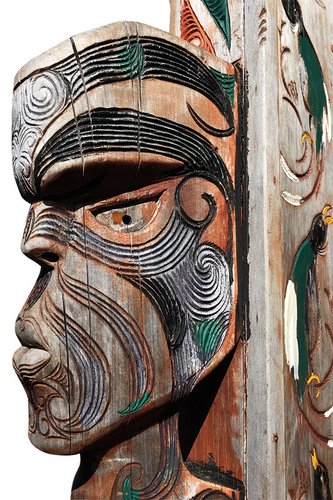

A wooden curving figure of a Māori male face on a totem pole.

Photo: Rafael Ben-Ari/ shutterstock.com

How can TK and TCEs be protected?

TK and TCEs are the creations of the human mind and are intellectual property. The intellectual property protection of TK and TCEs can be understood as taking measures to prevent their unauthorised use or misuse by third parties. The issues around such misuse of TK and TCEs are a big concern for Indigenous Peoples as it may cause spiritual, economic, reputational or cultural harm to them. However, the approaches to protecting TK and TCEs are often complex. One of the reasons is that the conventional intellectual property system was not designed and developed considering the special characteristics of TK and TCEs. For instance, TCEs are often of a collective nature, which makes it difficult or even impossible to identify their author or authors. As a result, they cannot be protected under the conventional copyright system, except for contemporary works that are based on TCEs. Moreover, the protection of intellectual property rights is often limited in time, which doesn’t fit the needs of TK and TCE custodians and holders well.

Despite these challenges, there are several options for the intellectual property protection of some aspects of TK and TCEs. Indigenous Peoples can use conventional intellectual property systems to protect and promote indigenous-owned businesses. As mentioned earlier, copyright might be used to protect some contemporary TCE-based creations. National unfair competition laws might be applicable when products are falsely labelled as Indigenous Peoples-made. For instance, in 2019, the Federal Court of Australia sanctioned a company that sold Aboriginal-made labelled souvenirs that were in fact manufactured in another country, which went against Australian Consumer Law.

Several countries have implemented specific provisions to their national intellectual property law that at some point reflect the needs of Indigenous Peoples. For example, New Zealand’s trademark law has specific provisions that help to prevent the registration of trademarks that would be considered offensive by Māori people. Furthermore, a number of countries have specific national laws, so-called sui generis laws, that address provisions for the protection of TK and/or TCEs. The Kyrgyz Republic, a country that is rich in its cultural heritage and traditions, has a law on the protection of TK and TK associated with GRs which aims to create conditions for fair distribution of benefits from the use of TK of the people of this country.

In some cases, non-legislative measures can be used to prevent the misuse of TK and TCEs by third parties. This could include awareness-raising campaigns, including in the social media, about the cases of misuse of TK and TCEs, or systematic activities that aim to make a community and its culture more understandable for and recognisable by decision-makers. For instance, a community of the Seto people in Pechory, Russia, had managed to fight against fake “Seto-made” handicrafts by raising awareness about the Seto culture in the region and informing tourists and locals on where authentic Seto products can be purchased.

What does WIPO do?

At the moment, there is no international instrument that would address the intellectual property protection of TK and TCEs. This issue has been discussed at the WIPO Intergovernmental Committee on Intellectual Property and Genetic Resources, Traditional Knowledge and Folklore (IGC) since 2001. The IGC is a forum where Member States develop an international instrument or instruments that would protect TK, TCEs and GRs. Indigenous Peoples, local communities, industries, civil society and NGOs can participate in the IGC as observers. Recently, there has been significant progress in the negotiations. In 2022, WIPO’s General Assembly decided to convene a Diplomatic Conference to Conclude an International Legal Instrument Relating to Intellectual Property, Genetic Resources and Traditional Knowledge Associated with Genetic Resources. The Diplomatic Conference will take place in Geneva from May 13th–24th, 2024. If successful, its outcome would be the adoption of an international treaty that aims to enhance the efficacy, transparency and quality of the patent system, and to prevent patents from being granted erroneously for inventions that are not novel or inventive with regard to GRs and TK associated with GRs. In the meanwhile, the IGC’s negotiations on the protection of TK and TCEs remain ongoing and will resume at its forty-ninth session in November/December 2024.

Apart from the normative work, WIPO organises activities and programmes for national governments, Indigenous Peoples, local communities and other stakeholders through its Traditional Knowledge Division. As an example, since 2019, WIPO has been organising training programmes for indigenous women entrepreneurs to help them develop their intellectual property strategy for their culture-based businesses and projects, connect them to useful experts within WIPO’s networks and build their capacity in other areas that are helpful for entrepreneurs. Besides, WIPO recently launched several activities that aim to build better understanding and potential collaboration between Indigenous Peoples from around the globe and the fashion industry on the use of TCEs.

Strengthening Indigenous Peoples’ control over TK and TCEs

To start with, learning about intellectual property rights, and paying attention to the national legislation could be helpful for Indigenous Peoples. Additionally, looking into best practices on the TK/TCE protection in other communities and countries could provide helpful hints and guidelines. Then, moving forward, legislative initiatives that aim to fill in gaps in the existing intellectual property protection and reflect the needs and rights of Indigenous Peoples, or lead to the adoption of specific sui generis regimes on the protection of TK and TCEs, are another important point. Finally, raising awareness about Indigenous Peoples’ rights and culture is essential. When other stakeholders, especially decision-makers, better understand the background, needs and challenges of Indigenous Peoples, this could help promote and ensure the communities’ rights regarding their TK and TCEs.

Anna Sinkevich is a Project Consultant at the Traditional Knowledge Division of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) and is based in Geneva, Switzerland. She holds a BA in Chinese Language and Literature and an MA in International Relations. Anna has been working at WIPO on traditional knowledge-related programmes and activities that support Indigenous Peoples since 2020. She is an Indigenous Evenki from Siberia.

Contact: anna.sinkevich@wipo.int

This article is not intended to reflect the views of the Member States or the WIPO Secretariat.

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment