Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Sustainable food systems need True Cost Accounting

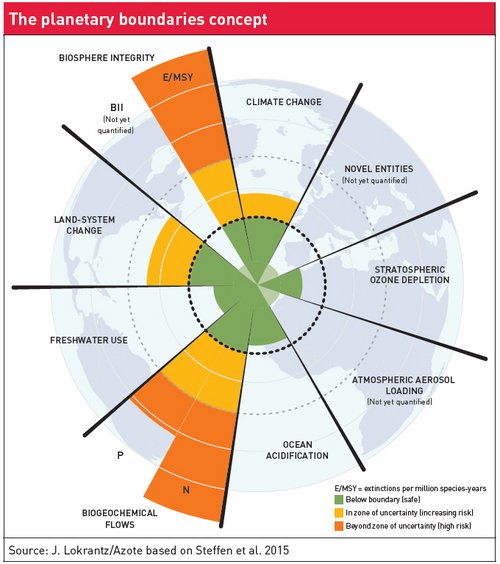

Johan Rockström’s well-known diagram on planetary boundaries very clearly shows several areas – climate change, biodiversity loss and the nitrogen/ phosphorus cycle – in which our planetary boundaries have already been exceeded (see page 10) by a substantial margin. One of the primary drivers is the agri-food sector. Agriculture is responsible for 23 per cent of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, making it a major contributor to the climate crisis. However, this is not reflected in our cost of production and food prices; the same applies to social injustices such as the use of child labour or exploitative working conditions.

At present, businesses are able to produce goods more cheaply if they can externalise more of their costs; in practice, these costs are passed on to the public. Firms which endeavour to adopt more equitable and sustainable business practices, such as fair trade companies and organic food producers, still occupy a niche in the market. Although their contribution to human well-being and public goods is demonstrably higher, their products tend to be the most expensive in stores and are therefore purchased less frequently. By contrast, products with the highest environmental costs are often relatively cheap. If nothing is done to address this systemic problem, the current environmental and social crises associated with our food production will worsen further. The market currently provides very few incentives to preserve and nurture. We face a dilemma, much of which has to be blamed on erroneous and inadequate accounting for the costs and benefits of food production. True Cost Accounting (TCA) can help to create more sustainable food systems with less harmful human and environmental impacts.

The positive effects would be felt mainly in the Global South. For example, in 2001, the cocoa industry announced that it aimed to end child labour in its supply chains by 2005. It is now 2022 and there are still more than 1.6 million children working in the cocoa industry in West Africa alone. It has become apparent in other sectors too that voluntary agreements and voluntary commitments are not enough to make the world a better place. However, if the costs of child labour were included on company balance sheets, this would provide an incentive to exclude it from the supply chains, spelling the end for child labour in this sector. We need to speak to businesses in a language they understand and here, it is the numbers and the bottom line that matter. A mechanism like True Cost Accounting is therefore essential to ensure that markets once again become functional and future-fit in a way which boosts human well-being.

What is True Cost Accounting?

True Cost Accounting is a new methodology which can be used to determine the real costs of a business, product or service. It not only assesses the direct production costs, such as the costs of raw materials and labour; it also takes into account how the business activities impact on the environment and society. These impacts are monetised – in other words, they are assigned a monetary value which is then shown on the company’s balance sheet. Alongside production capital, natural, social and human capital are thus accounted for. Greenhouse gas emissions and water pollution are examples of impacts on natural capital. Social capital covers aspects such as child labour, while human capital includes the payment of a living wage. In order to introduce a standard for True Cost Accounting along the value chain, various food sector companies in Germany, together with GLS Bank and the catholic development agency Misereor, set up the True Costs Initiative in 2019. In collaboration with the specialised consultancy Soil & More Impacts and TMG Think Tank for Sustainability, they developed the True Cost Accounting AgriFood Handbook as a tool which companies can use to expand the scope of their accounting into these areas.

Among other things, the Handbook supplies the monetisation factors that are required for accounting purposes. Identifying these factors is quite a daunting task – how do we account for something that was never assigned a value before? The True Costs Initiative makes use of the prevention costs approach here. Valid data are already available for natural capital, such as the costs per tonne of CO2 (116 euros/tonne) or the costs for the emission/build-up of soil organic carbon (100 euros/tonne). With social and human capital, it is a more difficult task. Human and social impacts are measured using DALY, a standardised method employed by the World Health Organization to compare the burden of different diseases. A DALY is equivalent to one lost year of “healthy” life. The sum of DALYs across a population affected by an impact driver (e.g. excessive work or child labour) measures the gap between the health status with and without the presence of the impact driver. For child labour, 80,000 euros per year and child is taken as monetisation factor, irrespective of whether the child lives in the USA or in Ghana.

What would be the effect of True Costing?

The balance sheet is the key document for businesses operating in a market economy. It provides information about the company’s financial status and its expected performance the following year. By expanding the scope of accounting to include True Costs, it would be possible to gain a far more realistic insight into a company’s status – benefiting not only its own management but also investors, insurers and rating agencies. The effects would be felt in a range of areas:

Price formation and companies’ purchasing decisions. If particularly harmful products are purchased, such as soya sourced from the Amazon, this would have a negative effect on the balance sheet and status report. Purchasing more sustainable alternatives, such as soya from Germany, would then be reflected in lower costs on the balance sheet. This would create an incentive for buyers to procure the more sustainable alternative. New prices would then be formed, making more sustainable products – previously at a disadvantage – relatively more affordable.

Lending and insurance. The better a company’s financial position, the more likely it is to be offered favourable lending terms by the banks as the risk of its defaulting on its loans is low. It makes a significant difference to a company if it has to pay an interest rate of three per cent or ten per cent on its borrowing. By referring to the TCA indicators shown on the balance sheet, banks would be in a much better position to make an informed decision about a company’s expected risks, including the likelihood of default. The same applies to insurers. At present, the balance sheet provides them with little more than a vague impression of the risks. But if it is clear that a company is making genuine efforts to establish resilient supply chains that are as sustainable as possible in order to minimise environmental and social risks, the insurance premium can be reduced accordingly.

Taxes. If the balance sheet is restructured and expanded to include True Cost Accounting indicators, a reform of tax law will also be required in order to reflect these changed conditions. Spending on water or soil conservation, for example, should then benefit from tax relief.

The long road to implementation

Some companies are already making efforts to integrate True Costs into their balance sheets and make them visible. One is Eosta, an organic fruit and vegetable importer in the Netherlands. In order to achieve a living wage, for example, the company pays ten cents more for each kilo of mangoes and passes this on to customers. However, to ensure that companies with equitable and eco-friendly business practices do not continue to face systemic disadvantages, a level playing field is required. Policy-makers have a role to play here. The German government’s coalition agreement states: “In dialogue with the business community, we wish to integrate environmental and, if appropriate, social values into existing accounting standards.” It is a good starting point, as it has boosted the topic’s political relevance. However, there does not yet appear to be any political will to implement this commitment on the part of the present government. It is a similar situation at international level. Although the topic of True Costs was discussed at the UN Food Systems Summit last year, we have not seen any meaningful policy action at the global level since then, unfortunately.

The crisis linked to the impacts of the war in Ukraine has again revealed the structural problems in the global agriculture and food system: the global food system is neither resilient nor sustainable. As products with high environmental and social costs are far cheaper than those produced in a sustainable and more equitable manner, demand for less sustainable products is particularly high. What we are dealing with here is market failure. True Cost Accounting can have a corrective effect. A reform of company accounting is therefore required at European level, if possible – and better still, at global level – in order to create a level playing field for everyone and thus build more sustainable agricultural and food systems. True Cost Accounting, with its inclusion of natural, human and social capital, is a key mechanism for achieving this goal.

Markus Wolter is an Agriculture and Food Policy Officer with Misereor, the German Catholic Bishops’ Organisation for Development Cooperation, which is based in Aachen. Before joining Misereor, he worked for the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) Germany and was an advisor on agriculture and development.

Contact: markus.wolter(at)misereor.de