Read this article in French

Read this article in French

Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Sustainable fisheries need transparency

Marine fisheries have become a critical resource fulfilling the economic, food security and nutrition needs of millions of people around the world. For millennia, those who dedicated themselves to fishing – either for family consumption, recreational interest or as a commercial activity – did not need to worry about the sustainability of this natural resource. Fish stocks replenished themselves with ease. But this is no longer the case.

The global Covid-19 pandemic struck at a time when the ocean was already under increasing threats from myriad impacts, including climate change, pollution and overfishing. According to the latest report on ‘The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture’ (2020) from the UN Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), more than 34 per cent of global fish stocks are already fished at biologically unsustainable levels – a share that has tripled in the last 40 years.

On a more positive note, the same report also states that “in general, intensively managed fisheries have seen decreases in average fishing pressure and increases in stock biomass, with some reaching biologically sustainable levels, while fisheries with less-developed management are in poor shape”. Indeed, over recent years, a growing global consciousness around the importance of ensuring sustainable fisheries has been witnessed – that is, fisheries are environmentally regenerative, economically viable and socially equitable. Unfortunately, increased understanding does not automatically translate into improved action. Around the globe, many marine fisheries are still poorly managed, and some are even fully unregulated.

Why transparency counts

Of the many interventions required to improve fisheries management and seafood sustainability, the public availability of basic, credible information is essential. This includes information like what the status of fish stocks is, how many vessels are allowed to fish, and under which conditions, how much is being caught, and how much is paid for the right to fish, etc. A lack of such information affects the capacity of governments to manage fisheries efficiently and sustainably, as well as the ability for effective oversight, accountability and public dialogue.

Perhaps the moment when transparency in fisheries management started garnering greater attention was when the FAO published its annual State of the World Fisheries Report in 2010. It was the first time transparency was mentioned prominently by the FAO as being of central importance to various problems affecting marine fisheries world-wide: “Lack of basic transparency could be seen as an underlying facilitator of all the negative aspects of the global fisheries sector – IUU fishing, fleet overcapacity, overfishing, ill-directed subsidies, corruption, poor fisheries management decisions, etc. A more transparent sector would place a spotlight on such activities whenever they occur, making it harder for perpetrators to hide behind the current veil of secrecy and requiring immediate action to be taken to correct the wrong.”

However, the scope of transparency should not be limited to only shining a spotlight on the activities of governments, or companies, in order to address issues such as illegal fishing or corruption. One relatively underappreciated value stemming from improved government transparency is an increase in the visibility of the entire fisheries sector, including actors who are often ignored or neglected. This is particularly relevant for specific fisheries sub-sectors (e.g. artisanal fishing) or certain groups (e.g. women), both of which play a vital role in ensuring people’s livelihoods, food security and culture, but are nevertheless often marginalised or undervalued in public debates and policy-making. The persistent lack of such information will likely be emphasised in 2022, designated by the UN General Assembly as the International Year of Artisanal Fisheries and Aquaculture.

Yet even today, in the age of information, there’s a lot of doubt and even secrecy about what’s happening in global fisheries. Too few governments are disclosing information on their fisheries sectors, ranging from information on laws, permits, fishing agreements and stock assessments, to financial contributions, catch data and subsidies. Likewise, not enough companies are reliably reporting on catch volumes and fishing practices. Furthermore, data that is publicly available is too often incomplete, old, unverified and difficult to understand for the general public.

How do we know whether the sector is managed in a sustainable way?

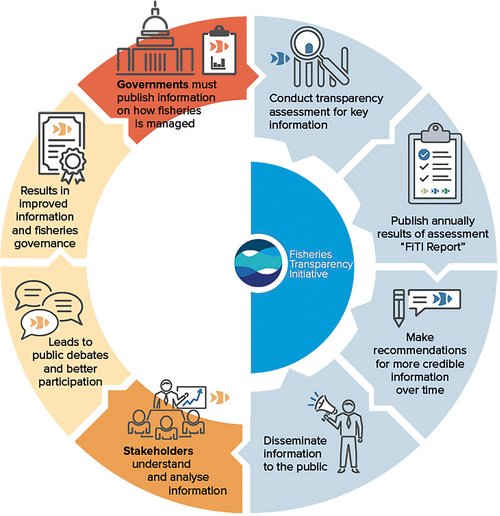

The Fisheries Transparency Initiative (FiTI) was created to address this problem on a global scale. It is a voluntary initiative that promotes transparency and collaboration in marine fisheries management. At the heart of the initiative is the FiTI Standard, the only global framework that defines what information on fisheries should be published online by public authorities. The FiTI Standard was developed over two years (2015–2017) in a global multi-stakeholder endeavour, involving representatives from governments, industrial fishing companies, artisanal fishing associations, civil society organisations and intergovernmental organisations, such as the World Bank, the European Commission, the African Development Bank and the FAO. The FiTI Standard covers twelve thematic areas of fisheries management:

Thematic areas of the FiTI standard

| # 1 | Fisheries laws, regulations and official policy documents |

| # 2 | Fisheries tenure arrangements |

| # 3 | Foreign fishing access agreements |

| # 4 | The state of the fisheries resources |

| # 5 | Large-scale fisheries |

| # 6 | Small-scale fisheries |

| # 7 | Post-harvest sector and fish trade |

| # 8 | Fisheries law enforcement |

| # 9 | Labour standards |

| # 10 | Fisheries subsidies |

| # 11 | Official development assistance |

| # 12 | Beneficial ownership |

In addition to defining for the first time precisely what transparency in fisheries management actually means, the FiTI is anchored on several core principles, such as:

- Transparency needs trust to be effective. Information has to be seen as fair, unbiased and not serving a certain political agenda or business interest. This is why the FiTI is set up as a multi-stakeholder partnership, where representatives from governments, business and civil society work together.

- Transparency is a transformative journey. The FiTI does not expect all countries to have complete data for each of the 12 areas from the beginning. Instead, public authorities must disclose the information they have, and, where important gaps exist, they must demonstrate improvements over time. As such, any country can implement the FiTI.

- Transparency has two sides, like a coin. The impact of the FiTI does not only lie in increasing the public availability of government information (visibility). It is equally important to ensure that such information allows others to draw reliable conclusions from it (comprehensibility).

Initial notable examples from Africa

While fisheries have been slow to catch on to the transparency wave, notable progress has been achieved over the last years. For example, Seychelles and Mauritania have become the first two countries to provide so-called FiTI Reports, outlining what fisheries information has been collated by national authorities, and whether this information is easily accessible to the wider public and seen as complete. Both reports have resulted in a range of previously unpublished information being made publicly available by national authorities for the very first time. The two reports were vetted by their National Multi-Stakeholder Group (NSMG) to ensure they can be seen as credible and trustworthy. Both groups – composed of equal numbers of representatives from government, the business sector and civil society – also formulated clear recommendations to progressively enhance transparency in their fisheries sectors over time.

Senegal, Cabo Verde and, very recently, Madagascar have all made public commitments to increase the level of transparency in their fisheries sectors through the FiTI. The FiTI International Secretariat, the initiative’s executive body – which relocated its operations from Germany to Seychelles in 2019 – is also working with stakeholders in several other countries, such as Peru, Ecuador, Mexico, São Tomé and Príncipe, Comoros and Bangladesh.

However, in order to turn these first notable examples into a global norm, additional issues need to be addressed, two of which are outlined here. Firstly, traditional ‘good governance’ arguments alone may not emphasise the importance (and political priority) that needs to be given to transparency to strengthen sustainable marine fisheries. This is particularly relevant in times when many governments are focusing on post-Covid-19 economic recovery. In the same vein, stronger correlation must be demonstrated between increasing public access to information and the ways in which transparency can improve government performance (e.g. through enhanced revenue collection, reduced spending) as well as to market-based incentive schemes (e.g. seafood certifications and sourcing policies, sectoral investments and trade agreements).

Secondly, transparency is still often misperceived as a notion with which governments can voluntarily choose to engage. The provision of information on a country’s marine fisheries sector is, however, increasingly becoming a legal requirement for governments, stemming e.g. from Freedom of Information laws. This implies that the public have a right to obtain environmental information (including on their country’s fisheries sector) with only limited, explicitly defined exceptions arising from confidentiality claims and security matters.

The importance of access to government information is also emphasised in the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Target 16.10 of the SDGs calls on all states to adopt legislation or policies guaranteeing the right to information. This is essential for both the achievement of Goal 16, but also as an enabler for achieving other SDGs.

Yet there are clearly still many actors who benefit from a lack of transparency. It needs to be acknowledged that if there were not such flagrant violations of good practices in fisheries management, there would be no need to insist upon transparency! Which means that there is still a lot do. The FiTI is therefore working not only with governments to increase the public availability of fisheries management information but also with non-governmental partners to promote an enabling environment that demands, understands, utilises and incentivises online government transparency.

Marine resources belong to everyone, and transparency is an essential first step in ensuring that our ocean and fisheries remain a source of income, sustenance, recreation and deep wonder for generations and years to come. For this, an immediate, global, and collective effort is needed. As Seychelles’ Minister of Fisheries and the Blue Economy, Jean-François Ferrari, stated in his opening remarks at the launch of the first ever FiTI Report: “[The Fisheries Transparency Initiative] is a tool for future development, and it must be our guiding principle to share all data and information on resources with all stakeholders.”

Sven Biermann is the Executive Director of the Fisheries Transparency Initiative (FiTI), based in the Seychelles. The FiTI is a global multi-stakeholder partnership that seeks to increase the level of government transparency in marine fisheries.

Contact: sbiermann@fiti.global