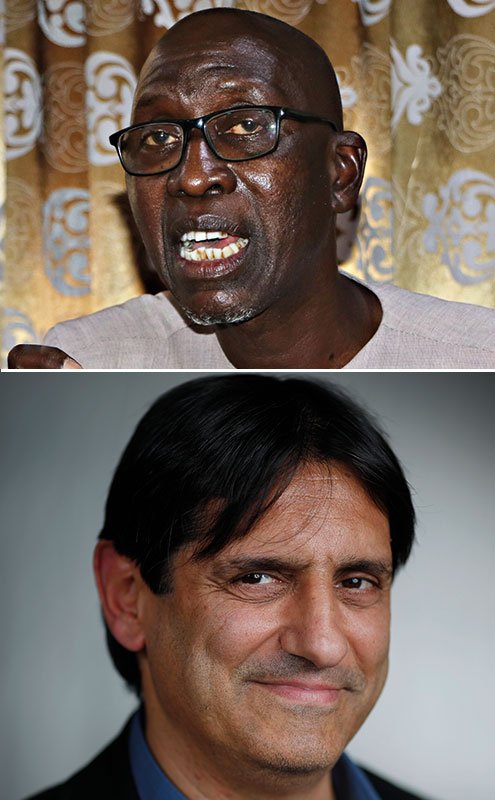

Gaoussou Gueye is President of the African Confederation of Professional Organizations of Artisanal Fisheries (CAOPA) and Chairman of the platform for nongovernmental actors in fisheries, newly set up by the African Union.

Francisco Marí has been working since 2009 as a project officer for lobby and advocacy work in the areas of Global Nutrition, Agricultural Trade and Maritime Policy at Brot für die Welt, focusing on food security, artisanal fisheries, WTO, EUAfrica trade and fisheries agreements, deep-sea mining and the effects of food standards on small-scale producers.

Read this article in French

Read this article in French

Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Building a better future for African coastal fishing communities

Fishing catches are stagnating at the global level, despite the ever increasing size of fishing fleets on the oceans. This situation is due to the overexploitation of fish stocks. Since the 1950s and the end of the World War 2, every country in the world has been racing to industrialise fishing. In Europe, Russia, North America and, more recently, Asia, massive subsidies are being employed to encourage this trend. These industrial fleets are now fishing in every ocean, including the territorial waters of the African countries. Currently, ever more and ever larger ships, using fishing techniques that are sometimes highly destructive, such as bottom trawling, are capturing fewer and fewer fish. In an effort to increase their catches, industrial ships are adding more and highly sophisticated instrumentation to locate and catch the remaining fish. This situation is threatening not only fish stocks, which are unable to renew themselves, but also coastal fishing communities, who account globally for two-thirds of catches destined for direct human consumption and 90 per cent of the sector’s employment.

CAOPA – a strong, self-established organisation of the artisanal fishing sector in Africa

To build a better future for coastal communities who depend on artisanal fishing for their living, like those in Africa, it is essential to re-shape the model of development in the fishing sector. Since its creation in 2010, the African Confederation of Professional Organizations of Artisanal Fisheries (CAOPA) has been advocating a model of development centred on sustainable artisanal fishing which emphasises informed participation by the women and men of fishing communities.

The International Year of Artisanal Fisheries and Aquaculture declared by the UN for 2022 is an opportunity for decision-makers to respond to the needs and problems faced by artisanal fishing, which constitutes a crucial source of employment, livelihood, food and nutrition for millions of families and coastal communities. The importance of artisanal fishing was demonstrated once again during the coronavirus pandemic. Despite the restrictions which have severely impacted African artisanal fishing and continue to do so, this crisis has brought into public view the capability of fishing communities to continue to provide essential food to the populations.

Orientation on promoting sustainable artisanal fishing is provided by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries in the Context of Food Security and Poverty Eradication. These guidelines advocate an approach based on human rights which goes beyond the fishing value chain to take into account questions of gender, social development, transparency, global warming and commerce.

What needs to be done

Concrete measures are needed to achieve this goal of establishing sustainable artisanal fishing. For the coming International Year of Artisanal Fisheries and Aquaculture, representatives of African associations of fishers and women working in processing and the fish trade organised within the CAOPA have identified three priority areas for action.

Priority access to fishing areas. The first priority is to guarantee African artisanal fishing secure access to resources. Anything which can be sustainably fished by artisanal fishing to feed populations should be left to artisanal fishing. This is particularly important for fish stocks which have strategic importance for food security, such as small pelagic fish in West Africa.

One tool for guaranteeing artisanal fishers access to fish is for states to grant them exclusive fishing rights in coastal waters. To ensure sustainable management of these coastal regions, they should be placed under co-management by the state and artisanal fishers, including appropriate measures to protect ecosystems, such as protected marine areas managed in cooperation with the communities dependent on fishing.

Another aspect which could improve fishers’ access to fish is reinforcing safety onboard small fishing vessels. Deep sea fishing has always been one of the most dangerous occupations in the world. Today, the scarcity of fish, and also global warming, which is drawing certain fish further off-coast towards colder water and triggers weather conditions that make shipping increasingly difficult, are factors making artisanal fishing even more dangerous as an occupation. Signature by African countries and implementation of International Labour Organization Convention 188 should make it possible to improve maritime safety for fishers. Training captains of small vessels, the use of new technologies (geolocation etc.) and raising awareness among fishers of the need to wear life jackets are all essential issues for safety.

Strengthening the processing sector dominated by women in artisanal fishing. A further priority is recognising and valorising the role of women in African artisanal fishing. Women are present at all stages of the artisanal fishing value chain in African countries: financing fishing trips, preparing fishing equipment, receiving and processing the fish. They are also the mainstay of the families and an essential link in getting fish to local and regional (perhaps international) consumers. Many women in artisanal fishing work in intolerable conditions, some breath-in smoke for more than ten hours a day and work without access to drinking water, electricity or sanitation, all for a starvation wage.

Consequently, on the occasion of this International Year, states should invest in the services and infrastructures required to improve working conditions for women in artisanal fishing. Some measures, such as the possibility of freezing catches or providing improved smoking ovens using solar energy, will also improve the quality of the raw material supply to the women and enable them to improve the processed product, ultimately resulting in a decent income.

African women in artisanal fishing are also involved in artisanal fish farming, which is a good way of supplementing their supply of raw materials and also covers periods when there is no fishing (during a closed fishing season for biological recovery, for example). States should accordingly support initiatives in this sector such as improving access to land and credit for the necessary equipment, or assisting research and development for an integrated artisanal fish farming.

Placing survival of coastal communities above the interests of the extractive and tourist industries. But none of these measures will bear fruit if artisanal fishing continues to be a marginalised sector in the national economy. Current discontent in African artisanal fishing is rooted not only in competition with industrial fishing but also – and particularly – in competition with other sectors included in “Blue Economy” strategies which are more powerful financially and politically, such as extraction of petroleum and natural gas, tourism and fishmeal factories, which pose a threat to the future of artisanal fishing.

CAOPA believes that development of the Blue Economy must proceed with caution. States should commission independent studies on the social and environmental impacts, with maximum transparency and with the participation by the affected coastal communities. No new use of ocean resources should be permitted or supported by lenders if it impacts negatively on marine ecosystems (oil pollution, for example) and on the activities of fishing communities who depend on these ecosystems for their living. It is equally important for states to implement transparent consultation and conflict-resolution mechanisms between users of maritime domains, with informed and active participation by the affected fishing communities.

Finally, it must be stressed that pollution of marine ecosystems and coasts by human activities, including plastic, is a disaster for the communities. It is important to promote the use of biodegradable materials, ban single-use plastics which pollute our oceans and invest in processing the waste which clutters our shores and our waters, including support to citizen initiatives for cleaning coastal areas.

Better prospects for young women and men

The future is full of challenges to African artisanal fishing communities, notably from the impacts of global warming which are already making themselves felt in our activities: increasingly difficult shipping and navigation conditions, coastal erosion, relocation of resources further offshore. However, the principal challenge to the future of our communities is giving young women and men a prospect of decent living and working conditions in artisanal fishing, and to stop them sliding into crime or embarking on the dangers of clandestine emigration.

The best way for African states to offer a future for this sector is to recognise the importance of artisanal fishing and place it at the focus of maritime policy, rural development and food security, developing national action plans which are transparent, participative and sensitive to gender issues for implementing the FAO Guidelines for sustainable artisanal fishing. We hope that the International Year of Artisanal Fisheries and Aquaculture will be the starting point for this movement in Africa.

Gaoussou Gueye is President of the African Confederation of Professional Organizations of Artisanal Fisheries (CAOPA). Gueye completed training as a navigator, worked on industrial fishing vessels and oil platforms and developed a ring of intermediate fish product dealers in order to secure better prices for fine fish, especially in international trade. In addition, he was active in the Senegalese Association of Artisanal Fisheries (CONIPAS) and was their Vice President up to 2009. Gueye is Chairman of the platform for nongovernmental actors in fisheries, newly set up by the African Union, and is a member of the Fisheries Transparency Initiative (FiTI) executive board.

Contact: caopa.peche@gmail.com

Francisco Marí has been working since 2009 as a project officer for lobby and advocacy work in the areas of Global Nutrition, Agricultural Trade and Maritime Policy at Brot für die Welt (Bread for the World), focusing on food security, artisanal fisheries, WTO, EUAfrica trade and fisheries agreements, deep-sea mining and the effects of food standards on small-scale producers. He represents Brot für die Welt on the boards of the EU Long Distance Action Committee (LDAC) and the Fisheries Transparency Initiative (FiTI), on the advisory board of the Coalition for Fair Fisheries Agreements (CFFA), on the Stakeholder Forum of the German Alliance for Marine Research and on the International Council of the World Social Forum.

Contact: francisco.mari@brot-fuer-die-welt.de