Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Boosting transdisciplinary research for small-scale fisheries

Small-scale fisheries occur in aquatic ecosystems anywhere in the world, often in rural and isolated areas. They are diverse in their characteristics, complex in their organisation and dynamic in their operations. Therefore they present a major challenge for research and a ‘wicked problem’ for management and governance. This was the impetus for the establishment of the Too Big To Ignore (TBTI) global research network in 2012, which has brought together researchers around the world to work collaboratively with each other and with small-scale fisheries communities and various supporting organisations.

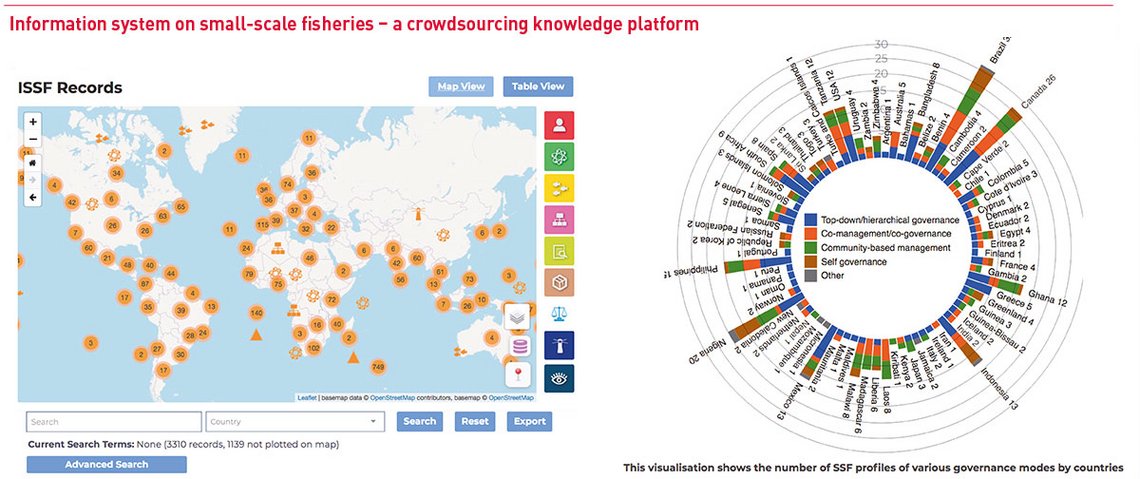

The primary aims of TBTI are to enhance knowledge about this important sector and address concerns and challenges affecting their viability and sustainability. With the contribution of more than 600 members, TBTI has been able to provide detailed insights about small-scale fisheries, based on more than 300 case studies from at least 80 countries. This work has been disseminated, not only through conventional academic outlets, such as peer-reviewed books and journal articles, but also as free online publications, available for download from the TBTI website. Furthermore, TBTI has developed a comprehensive Information System for Small-scale Fisheries (ISSF) based on a crowdsourcing platform that enables data sharing and broad-based synthesis (see Figure). ISSF contains information about various aspects of small-scale fisheries research, key characteristics of small-scale fisheries around the world, and examples of injustices in them.

In the past two decades, small-scale fisheries have received heightened attention from governments and non-governmental organisations, funders and donors, as well as scientific communities that are working in parallel and in concert to support and promote sustainable enterprises. One of the key milestones was the endorsement of the Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries (SSF Guidelines) by FAO member states in 2014. Among other things, the SSF Guidelines recognise the important role of academia in building more sustainable and socially just fisheries, where small-scale fisheries can continue to play a strong role in the ocean economy.

All these efforts make it increasingly difficult to ignore these enterprises. Yet, a better recognition of them, especially of their immeasurable contribution to food security, poverty alleviation, viable livelihoods and wellbeing of millions of women and men involved in pre-harvest, harvest and post-harvest activities, is not a sufficient condition for addressing marginalisation and vulnerability in small-scale fisheries. The threat to their viability and sustainability becomes particularly visible with the discussion about 'Blue Growth' and 'Blue Economy' initiatives, especially those that tend to exclude the sector.

Building transdisciplinary capacity in research and governance

As noted, issues and challenges affecting small-scale fisheries are complex. These factors also evolve with the compounded changes, related to climate, economy, technology, and institutions. Therefore, research questions must be carefully framed in order to address multifaceted concerns in the sector. The five big questions driving TBTI research illustrate the need for comprehensive knowledge about small-scale fisheries (see Box). Addressing these questions would then require a broad range of expertise and experience from scientists from different disciplines, fisheries professionals, and knowledge holders like fishers, elders and local leaders.

A transdisciplinary (TD) process to co-identify the problem, co-design the studies and consequently co-create the knowledge can then take place, leading to a better, more holistic way of framing the questions, and to a research design that not only enhances learning but also nurtures respect and appreciation between the people involved in research. The TD principle underlies what TBTI is doing, including how it is organised and functions, and in the offering of the online learning platform to help build TD capacity in research and governance.

The big five questions driving TBTI transdisciplinary research

1. What options exist for improving the economic viability of small-scale fisheries and increasing their resilience to large-scale processes of change?

2. What aspects of small-scale fisheries need to be accounted for and emphasised in order to increase awareness of their actual and potential social contributions and their overall societal importance?

3. What alternatives are available for minimising environmental impacts and fostering stewardship within small-scale fisheries?

4. What mechanisms are required to secure livelihoods, physical space and rights for small-scale fishing people?

5. What institutions and principles are suitable for the governance of small-scale fisheries?

To some, this may seem cumbersome, and perhaps unnecessary. But investment of time and resource in getting research and fisheries governance right is the best way forward, given that small-scale fisheries are too important to fail. Lessons from past fisheries management approaches from around the world, especially about the negative consequences of some ill-suited management decisions on small-scale fisheries, have been sending clear signals of how technical fixes no longer work. Examples include the application of tools like individual transferable quotas (ITQs) that tend to concentrate quotas in a few companies or how the designation of some marine protected area (MPAs) prevents small-scale fisheries from accessing the fishing ground. A nuanced approach to fisheries management, grounded in mutual respect and agreed-upon principles, applied with sensitivity and careful consideration for the most marginalised and vulnerable groups, is called for.

Demands for interdisciplinary and TD research have been heightened, with growing concerns about climate change, global food security and environmental sustainability outlined in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The first step in tackling these issues is to build innovative research and governance capacity.

Mobilising for “Blue Justice”

With the Blue Economy/ Blue Growth agenda being enthusiastically adopted by both the government authorities and large-scale, ocean-based industries around the world, as seen in the Blue Economy Conference held in Kenya in 2018, it is more important than ever for the research community to engage in the debate about the future of the ocean and fisheries sustainability. In our forthcoming volume “Blue Justice: Small-Scale Fisheries in the Sustainable Ocean Economy”, we argue that if governments do not earnestly implement the SSF Guidelines, the Blue Economy will come at a loss for the sector. If governments fail to secure sustainable small-scale fisheries, a sector that is more sustainable and climate-friendly, and that delivers on secure and just future for the millions of people who depend on fisheries for livelihoods and a way of life, there is little chance to achieve fisheries and ocean sustainability (SDG 14) and other related SDGs.

As a concept, “Blue Justice” speaks to the importance of inclusion of small-scale fisheries and community members as stakeholders; of paying a closer look to the power imbalances and inequity that are happening in the ocean space, mostly in connection with the Blue Growth/ Blue Economy agenda, as well as in the broader context of the development in marine and inland fisheries. This is largely an issue of power and the ability of small-scale fisheries to withstand the pressures they are experiencing when new ocean development projects take place in the areas that they have been able to access, on land and at sea. By bringing in basic principles of justice to recognise that small-scale fisheries have rights and priorities that cannot be ignored, the Blue Justice lens encourages governments and all sectors of the society to help restore justice for small-scale fisheries, making up for past wrongs and enabling them to deliver on their potentials.

Blue Justice is also about the need to build upon the existing capacities and capabilities of small-scale fisheries people, so they can be more robust, resilient, and creative. In other words, it is about integrating the sector as one of the key actors in a sustainable ocean development strategy – one that centres on small-scale fisheries, their nature and values, rather than one that excludes them.

Levelling the playing field

Much of the TBTI research effort has been focused on improving fisheries governance for small-scale fisheries such that the governance system, including fisheries institutions and regulations, is based on universal principles, like human rights, dignity, and justice. Appropriate processes and mechanisms need to be put in place to strengthen the involvement and engagement of small-scale fisheries people in decision-making. This may require reform and transformation in the governance system so that it becomes more interactive and collaborative. Small-scale fisheries people have a democratic right, indeed a human right, to be involved in governance processes and decisions that affect their livelihood opportunities, with respect for their cultural practices and norms, which the SSF Guidelines say should happen. All countries have a starting point for this, as signatories of many relevant international conventions and agreements. Still, more effort is required, legally and otherwise, before the playing field is levelled in a way that would sustain small-scale fisheries.

Ratana Chuenpagdee leads the Too Big To Ignore (TBTI) Global Research Partnership for Small-Scale Fisheries. Ratana is a university research professor at Memorial University in St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada, specialising in fisheries governance. She has conducted research in many countries around the world, including Cambodia, Malawi, Mexico, Spain and Thailand, where she’s from.

Vesna Kerezi is a project manager and communication specialist who has been working with TBTI since 2013. A geographer by training, she holds a MSc from Memorial University, Canada. Her interests lie in human dimensions of small-scale fisheries, social science communication and knowledge mobilisation.

Svein Jentoft is Professor Emeritus at the Norwegian College of Fishery Science, UiT –The Arctic University of Norway. His long career as a social scientist specialising on fisheries management and fisheries communities has yielded numerous publications, including the latest TBTI E-book ‘Life Above Water’ (2019).

Contact: ratanac@mun.ca

References and further reading:

Too Big to Ignoere website: http://toobigtoignore.net

Information System for Small-scale Fisheries (ISFF): issfcloud.toobigtoignore.net

FAO (2015): Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries in the Context of Food Security and Poverty Eradication. Rome. https://www.fao.org/voluntary-guidelines-small-scale-fisheries/en/