Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Building resilience to food crises – an integrated approach from Mali

Every year, food crises in the Sahel region cause food insecurity for six to ten million people. While in all Sahel countries, populations are structurally in the grip of hunger and malnutrition, Mali is the theatre of successive food and nutrition crises aggravating an alarming chronic situation. Food insecurity essentially appears in two forms – in a cyclical food and nutrition insecurity and in a structural food and nutrition insecurity. The cyclical form of food insecurity is caused by climate change events at almost regular intervals. These shocks also affect the behaviour of vulnerable households, which abandon good practices that do not provide them with immediate solutions. The structural food and nutrition insecurity is caused by fragile ecosystems and degradation of natural resources, poor performance of production systems, monetary and non-monetary poverty, inadequate feeding practices, shocks and aggravating factors, as well as internal and external conflicts.

Joining forces for resilience in Sahel

In 2012, the region’s stakeholders decided to combine their efforts and created the Global Alliance for Resilience in Sahel and West Africa (AGIR). AGIR is a framework that helps to foster improved synergy, coherence and effectiveness in support of resilience initiatives in the 17 West African and Sahelian countries. The Alliance is placed under the leadership of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the West African Economic and Monetary Union (Union économique et monétaire ouest-africaine – UEMOA) and the Permanent Interstate Committee for Drought Control in the Sahel (Comité permanent inter-État de lutte contre la sécheresse au Sahel – CILSS). It is based on existing platforms and networks, in particular the network of food crises prevention (Réseau de prévention des crises alimentaires – RPCA).

Building on the ‘Zero Hunger’ target by 2030, the Alliance is neither an initiative nor a policy. It is a policy tool aimed at channelling efforts of regional and international stakeholders towards a common results framework. A Regional Roadmap, adopted in April 2013, specifies the objectives and main orientations of AGIR. In 2012, Mali joined AGIR and committed to strengthen resilience of vulnerable populations to food and nutrition insecurity. Here, resilience is defined as “the capacity of households, families, communities and vulnerable systems to face uncertainty and the risk of shock, to resist to shock, to answer efficiently, to recover and to sustainably adapt themselves”. This commitment had been confirmed at the RPCA’s members meeting in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire in November 2013. Later, a focal point within Mali’s Ministry of Agriculture was appointed, and a working group was set up in January 2014.

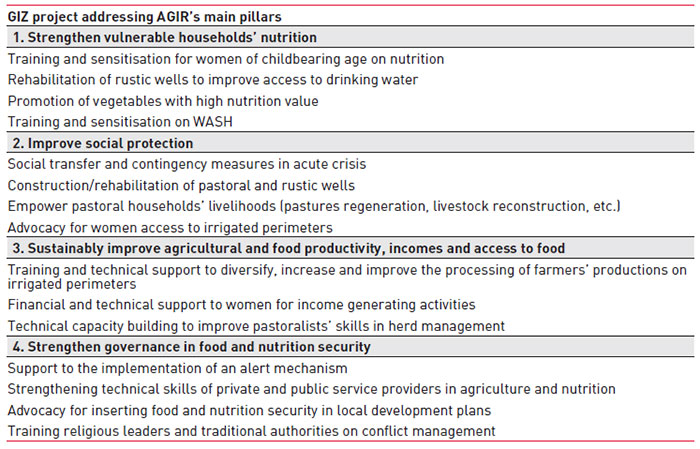

As the situation is likely to be the same in all Sahel countries, AGIR’s common strategy has been designed for targeting the most vulnerable population. Vulnerable people are the most exposed to risks of recurring shocks, in particular marginalised rural households in fragile ecological areas as well as poor urban households in the informal sector. Among these populations, special attention is paid to children under the age of five, pregnant and breast-feeding women, women heads of household and the elderly. These groups were identified through several analyses, conducted by a group of experts, addressing each of the four AGIR pillars (see Box above). In these analyses, vulnerabilities are distinguished such as vulnerability of livelihoods and social welfare, nutrition vulnerability, agricultural vulnerability, vulnerability to shocks (floods, droughts, pests, etc.), factors aggravating food and nutrition vulnerability, and multidimensional vulnerability, resulting from the synthesis of previous analyses.

By combining actions in several sectors and addressing the four pillars of resilience as defined by AGIR, we reduced severe food insecurity of households, as measured through the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)’s Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES), from 42 per cent to 16.5 per cent within the last three years (see Box below).

The Food Insecurity Experience Scale

The Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES) was developed by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations in the context of the “Voice of the Hungry Project” implemented in several African countries. It can be analysed at individual or household level. The FIES consists of a set of eight questions regarding people's access to adequate food ranging from “worrying about the ability to obtain food” to “experiencing hunger”. Clustering the answers allows to identify individual households and the percentage of households in a given population that are food secure or mildly, moderately or severely food insecure.

From political frameworks to the ground

In 2015, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) started its interventions in the region of Timbuktu in the Niger Inland Delta in Mali. The project “Food Security, Enhanced Resilience” is part of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ)’s special initiative “One World – No Hunger”. It aims to strengthen resilience to food crises of those populations in risk of food insecurity, particularly refugees and internally displaced persons in the process of reinstallation and/or returning to their country. A special emphasise is put on dietary diversification for women of childbearing age. With a total amount of 30,000 beneficiaries, the project lasts until 2023.

Applying the nexus

The project adopted a multisector approach combining actions in agriculture, water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH), nutrition, and human capacity development through three main components addressing refugees and internally displaced persons in the process of reinstallation and/or returning to their country.

Introducing new technologies, irrigated agriculture, including pastoralism, will make more nutrition-sensitive as well as more resilient to food crises. Almost one hundred wells were already restored or (re-) built to improve access to drinking water for 3,266 agro-pastoral households and their cattle. In the 2017 acute crisis period, 809 households benefited from cash-for-work programmes through pasture-sowing activities, and 749 other households were provided with 48,000 West African CFA Francs (XOF) each to purchase food for themselves and fodder for their cattle. More than 930 ha of pastureland has already been regenerated to improve pastoralists’ livelihoods and fodder sources for the livestock. Technical and financial support was given to 20 groups (about 200 persons) for the implementation of income-generating activities (cattle fattening, small shops, truck farming). The 2017 balance sheet reveals encouraging results with an average return of investment increase of more than 50 per cent of beneficiaries’ starting capital. In addition, trainings on WASH, agriculture, pastoralism, nutrition and conflict management for public and private actors, 54 per cent of them women, took place.

Communicating social and behaviour change for healthy and varied diet shall be achieved by training and introducing adapted and affordable technologies to sensitise on good practices in hygiene and sanitation throughout the whole process of transformation and food consumption at household level. Technical advice and material support contributed to improving access to rice and vegetables with a high nutrition value for more than 10,800 persons. This support also facilitated financial accessibility to healthier food for women by generating income opportunities. In addition, more than 2,000 women were trained in best practices in nutrition. Thirty per cent of them are already applying newly learnt culinary recipes.

Capacity building as a multisector approach of resilience to food crisis for public, private or civil society actors involved in the project implementation at national, regional and local levels is still a challenging venture.

Remaining challenges

To strengthen co-ordinating of resilience actions at national level, a mechanism will be set up through a co-ordination, monitoring and evaluation unit. This unit is to measure the progress made in the implementation of the country’s resilience priorities. The mechanism will build on the institutional mechanisms put in place to facilitate a multisector approach. This system is to bring together the four pillars of resilience as defined by AGIR. The Ministry of Agriculture, the initial institutional anchor of AGIR in Mali, acts as a co-ordinator to link up with the relevant departments of other ministries, their decentralised services and local authorities.

The most important challenge we face now is the non-functionality of regional and local entities within the national food security system. Our partners’ ability to continue best practices at national, regional and local levels still needs to be improved. In this context, it is important to find participatory approaches to involve all stakeholders. For a common understanding and giving an overview, team and stakeholder meetings are taking place on a regular basis. An institutional enhancement action plan was formulated aiming to strengthen national, regional and local authorities’ capacities to take into consideration resilience to food and nutrition crises when co-ordinating food and nutrition security action plans at each level. This can only be done if resilience to food and nutrition crises is considered in the economic, social and cultural development plan at local level.

Raymond Mehou, an agricultural economist, has worked as Country Manager for the GIZ Programme in Mali since June 2017.

Mohomodou Atayabou, a trainer and sociologist, started working as National Coordinator for the GIZ Programme in Mali in September 2015.

Contact: raymond.mehou@giz.de

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment