Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

The two sides of rural-urban migration

Kyrgyzstan is one of the five Central Asian countries which gained independence in the course of the disintegration of the Soviet Union. It is located between Kazakhstan at its northern border and China, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan at its southern border. Most people attribute high mountains, nomadic culture and yurts to Kyrgyzstan. In fact, the country hosted the second World Nomadic Games in September this year.

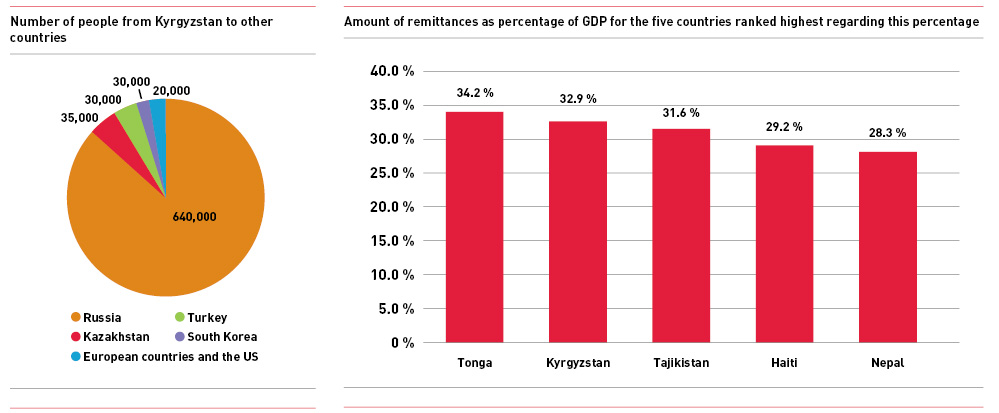

Less known to most people, but of crucial importance to Kyrgyzstan, is labour migration and the associated inflow of money through remittances. From a population of about six million people, around 800,000 (some estimates even refer to one million) work abroad. The total amount of money transferred from migrant labourers into Kyrgyzstan was 32.9 per cent of GDP in 2017, according to World Bank data. This figure ranks Kyrgyzstan second world-wide in terms of remittances compared to GDP, only surpassed by Tonga (see right Figure below).

The major destination for migrant workers is Russia with an estimated 640,000 Kyrgyz people working there, followed by neighbouring Kazakhstan (see left Figure below).

In Russia, the major destination is Moscow, followed by other big cities like Saint Petersburg, Yekaterinburg, or Novosibirsk, which is also easily visible on the flight schedules of Bishkek and Osh Airports. Many migrants work in informal contexts so that only estimates can be provided on the actual number of people. According to a 2017 study from the University of Central Asia, about three quarters of the migrants in Russia work in the sectors of trade and retailing, gastronomy, and construction. The reasons for labour migration are low salaries and unemployment in Kyrgyzstan. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), current average monthly earnings of employees are 14,217 Som (USD 205) in Kyrgyzstan, compared to 38,609 Rubles (USD 588) in Russia and 163,725 Tenge (USD 450) in Kazakhstan.

Migration is also an issue within Kyrgyzstan, since more and more people are moving to the capital, Bishkek, and to a lesser extent to Osh, the second largest city. This migration adds to the lack of labour for rural households. While migration to Russia and other countries is associated with an inflow of money into Kyrgyzstan, migration inside the country mostly involves an exchange of money and food. Family members who have moved to the city receive food, mainly potatoes, vegetables, fruits and meat, so that many people do not have to spend much money on food. In turn, the new city citizens send money back home.

Changing rural household structures

In terms of its economy, Kyrgyzstan is divided into north and south. The northern part with Bishkek is richer than the southern part of the country. The south faces high population pressure and shortage of land, and in general is more rural and dependent on agriculture than the north. This is reflected in migration numbers, as the share of households with at least one migrant is highest in these southern provinces, at 34 per cent for Batken, 29 per cent for Jalalabat and 25 per cent for Osh. In the northern provinces this share of households is only between 1.5 per cent and 4 per cent. In the southern provinces, with their high share of rural inhabitants, many households depend on migration in order to satisfy their daily needs for food.

Migrants from Kyrgyzstan are mostly younger than 30 years and are mainly men, although women are catching up. Twenty per cent of the migrants hold a higher education degree, 27 per cent have had vocational education and training, about 40 per cent have completed school education, while 13 per cent have no formal education certificate. Slightly less than a third of the country’s population (64 per cent) are rural. Since most migrants are men, many households lack labour in agriculture. This is aggravated by the share of the migrants who work in construction, as they out-migrate during the summer. Many households respond to the lack of labour at home by switching to crops with lower labour requirements. Instead of maize or wheat, they grow lucerne, for example, which is used as animal feed for the households’ own requirements or for sale. These crops are planted every five years and just need to be harvested two or three times a year. Others concentrate on gardening and fruit trees, though mostly for subsistence or to deliver small amounts to local markets. While gardening is very labour-intensive, it is traditionally regarded as a “woman’s task”. This is also because it is hardly or not at all mechanised. Nevertheless, one effect of this migration-driven gender imbalance is that women are empowered since they often have to act as household heads.

Remittances sent back home are mainly used to meet basic needs. About 50 per cent of the remittances are spent on food and clothing by the family members back home. Around 30 per cent are used to buy apartments or build or renovate houses. Next to these purposes, remittances also contribute to supporting education and healthcare of family members, buying farm equipment, livestock and cars, and paying for celebrations (weddings and funerals). For the latter purposes the various studies give somewhat different degrees of importance. Here, it should be noted that livestock has a banking function for many families all over the country. The overall picture suggests that only a very small proportion is used for investments or as a basis to set up a business.

Remittances cut both ways

The impact of remittance flows is ambivalent. On the one hand, households are brought into a dependence on remittances, which may transport a wrong and too optimistic picture of the financial situation and perspectives of the households, because the inflow of remittances is often taken for granted and is perceived as a continuous part of household income. However, whether this income can be sustained at certain levels and for long-term perspectives is beyond the control of the households and migrant workers. If a crisis sets in, such as the economic crisis in Russia after 2013 (see below), migrant workers are the first to be laid off and sent home, with a severe reduction in household income and overall remittances.

The occurance of such crises or other political changes that impact on migration cannot be controlled by the migrants and their dependent families. It is noteworthy in this context that, according to World Food Programme (WFP) standards, Kyrgyzstan is not so food insecure that it justifies interventions by the WFP, but because of the importance of migration and remittances, Kyrgyzstan is considered very vulnerable, so that the WFP remains in the country. For governments, migration provides a biased picture of their countries’ economic situation due to the constant inflow of money. Governments may become lazy doing reforms, as they count on the steady inflow of remittances.

On the other hand, returning migrants bring new skills from abroad, chiefly in construction, services, catering and trade. Migration has sparked improvements in communication infrastructure, and the need for and pressure of reliable and efficient money transfers has resulted in an enhanced banking system.

No reliability

After disintegration of the Soviet Union, the newly independent countries fell into a severe economic crisis, and industry largely broke down. In Kyrgyzstan, the collective farms (Kolhozes and Sovhozes) were dissolved very quickly, which resulted in a huge number of smallholder family farms often lacking good access to machinery and other inputs. Agriculture shifted largely to subsistence agriculture to feed the households in the countryside, but also to support family members in the cities.

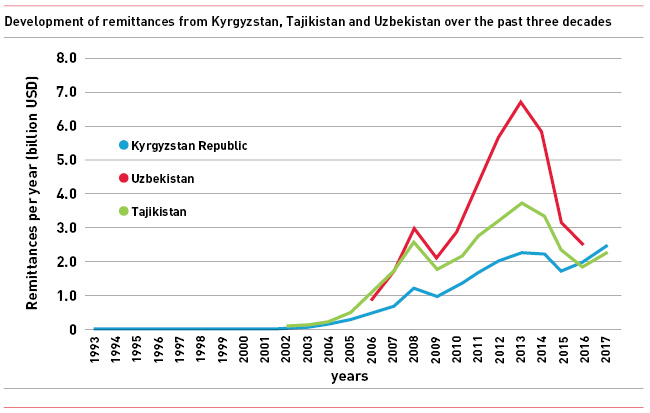

After the 1990s, when the Russian economy started to grow, people from Kyrgyzstan, but also from neighbouring Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, began to migrate and take up work in Russia. There was a steady increase of remittances – in some years with annual growth rates of 50 per cent – until 2013, interrupted only shortly by the economic crisis in 2008. After 2013, Russia suffered from an economic crisis, which resulted in a significant reduction of migration and flow of money to Central Asia, in particular in Uzbekistan. From 2015 on, migration picked up again, and Kyrgyzstan has surpassed its former peak of 2013 with annual remittances of USD 2,485,778,060 in 2017 (see Figure).

Now Kyrgyzstan is the major origin of migrants to Russia, since the country joined the Russia-led Eurasian Economic Union in August 2015. Before Kyrgyzstan eventually became a member, simplifications for Kyrgyz migrant workers had been one of the most, if not the most important issue for the country. Now, many simplifications (e.g. registration is easier, work permits are no longer needed, labour market quotas have been lifted, and there is access to social benefits) are in place for Kyrgyz migrants, but not for Tajiks or Uzbeks, because their countries are not members of the Eurasian Economic Union. Therefore, migration from the latter two countries lags behind Kyrgyzstan. Before mid-2015, 194,000 Kyrgyz citizens were blacklisted by the Russian authorities for immigration rule violations. At the end of October 2015, some 76,000 Kyrgyz citizens were deleted from these lists. This has eased access to the Russian labour market. Kyrgyzstan is a driver for Tajikistan and Uzbekistan to move closer to Russia or at least keep ties with it and benefit from migration.

Niels Thevs has headed the Central Asia Office of the World Agroforestry Centre in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, since its opening in 2015.

Begaiym Emileva joined the office in July 2018, after receiving her Master’s Degree in Horticulture.

Kara Lorraine Canlas is enrolled in the International Master Study Programme Global Change Management at Eberswalde University for Sustainable Development, Germany, and worked as an intern for the World Agroforestry Centre, Central Asia Office, in 2018.

Contact: n.thevs@cgiar.org

References and further reading:

- https://www.osce.org/odihr/269066?download=true

- https://data.worldbank.org/indicator

- https://24.kg/english/70076_Amount_of_money_transferred_by_Kyrgyz_migrants_to_homeland_in_2017/

- http://ucentralasia.org/Content/Downloads/UCA-IPPA-WP-39%20International%20Labour%20Migration_ENG.pdf

- http://www.osce-academy.net/upload/file/Policy_Brief_21.pdf

- https://www.ilo.org/gateway/faces/home/ctryHome?locale=EN&countryCode=KGZ®ionId=2&_adf.ctrl-state=kp7rm2gsg_4

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment