Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Innovations for women’s access to land

Women make up 57 per cent of the workforce in sub-Saharan agriculture. Yet, only 15 per cent of landowners are female, and even their land use rights are usually precarious. In rural Burkina Faso, where customary law prevails, women’s land use rights can be withdrawn at any given time – commonly by their husbands. Consequently, many women are unable to make long-term investments in land productivity, such as soil fertility measures, which limits their potential to enhance agricultural production, incomes and standard of living. In many ethnic groups in Burkina Faso, widows experience less tenure insecurity. Their land use rights are relatively stable, as these are of unlimited duration. However, widows only inherit permanent use, and no ownership rights, under customary law.

While major land rights reforms are ongoing in many African countries, the prospects of significant change for women remain weak. In Burkina Faso, most of them still face tenure insecurity – even in cases where family land ownership has been formalised. It is against this background that GRAF (Groupe de Recherche et d’Action sur le Foncier; Research and action group on land rights; see Box) and TMG Research have tested an instrument to secure women’s access to land through voluntary tenure arrangements between, in most cases, husband and wife. Today, in total, 228 women have secured access to land in the village of Tiarako, where this mechanism was piloted.

About Graf

Founded in 2001 and based in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, the Groupe de Recherche et d’Action sur le Foncier (Group for Research and Action on Land Tenure – GRAF) is a major actor in national land tenure reforms. It has produced basic documents and moderated and actively participated in multi-stakeholder thematic forums which helped formulate national policies for securing land tenure in rural areas. The network also actively supported drafting of Law 034-2009 in 2009, and has since contributed actively to enforcement and outreach of this law by means of projects and programmes for safeguarding vulnerable groups. On the international level, GRAF has (inter alia) organised regional conferences for West and Central Africa and Madagascar on formulating voluntary guidelines for governance on the tenure of land and other natural resources.

The gender gap in policy implementation

Most land in rural Burkina Faso is still managed under customary law. Land law reform since 2007 and the adoption of land law 034-2009 represent attempts to formalise customary claims to land. In addition, land law 034-2009 reinforces the decentralisation of land governance. Due to lacking financial resources and a consequent limited number of land governance institutions at sub-national level, the land law has so far only been realised in 112 out of 351 districts.

The legal framework for land governance recognises equal rights for men and women. Under the land law 034-2009, women, like men, can obtain formal land possession certificates as well as inherit land. The land law further promotes allocation of at least 30 per cent of state-owned agricultural land to women. Except for these provisions, current land policies do not actively endorse instruments to address women’s restricted access to land within the family’s land ownership as practised under customary law. When land ownership is formalised and secured, it is frequently done so in the name of the family head, mostly a man, or in some cases of widowed women who lead the household.

The disadvantaged tenure situation of married women, and patriarchal control of land, is likely to persist even with implementation of the land law advancing. Similarly, there are probably not going to be any significant changes in the situation for bachelor women through the formalisation of customary land rights in the name of the head of the household. They continue to be recognised as labourers on their family farm, or may be allocated a small plot with insecure use rights.

Initiatives that have aimed to facilitate the formalisation of land rights for women remain limited. One of them is the project “Securing tenure for women in Niéssin and Panasin in the rural district of Cassou”, implemented by GRAF as well as the Millennium Challenge Account, a development co-operation fund by the US government that financed, among others, a pilot programme to formalise land rights in Burkina Faso.

A complementary instrument to the land law

Against the background of lacking policies and programmes to tackle women’s tenure insecurity in a comprehensive manner, the process showcased in this article addresses a major gap. GRAF and TMG Research have tested the feasibility of voluntary intra-household tenure arrangements in the village of Tiarako, Houet province. This initiative was carried out under the research project accompanying the global programme on “Soil Protection and Rehabilitation for Food Security”, implemented by Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) on behalf of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ).

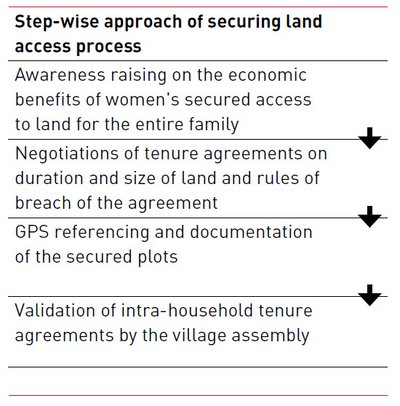

In essence, the leaders of the family farm and other family members – typically their spouses – agree on the duration of land use rights and rules of termination of this agreement. The process of testing this instrument involved a range of local stakeholders – the villagers, their traditional leaders, the district administration and public extension service providers. In regular multi-stakeholder dialogues and workshops, facilitated by GRAF and TMG, the mechanism was developed, assessed and adjusted. The implementation in the village followed a step-wise approach (see Figure). The first phase was dedicated to awareness raising of the economic benefits of women’s secured access to land, followed by negotiations of tenure agreements. GRAF experts led and facilitated dialogues through village assemblies, focus group discussions, and one-to-one conversations. After men and women had agreed on the transfer of land use rights, the secured plots were GPS-referenced, documented and validated by the village assembly under the presidency of the mayor.

The implementation in the village followed a step-wise approach (see Figure). The first phase was dedicated to awareness raising of the economic benefits of women’s secured access to land, followed by negotiations of tenure agreements. GRAF experts led and facilitated dialogues through village assemblies, focus group discussions, and one-to-one conversations. After men and women had agreed on the transfer of land use rights, the secured plots were GPS-referenced, documented and validated by the village assembly under the presidency of the mayor.

Since this instrument does not require legal titling, it needs relatively few financial resources. With a spending of less than 50,000 euros over a period of nine months, 185 plots, 2.2 ha on average and 407 ha in total, for more than 228 women have been secured. Ninety-six per cent of these land use agreements are for an unlimited period. According to the villagers, over 90 per cent of the men who are able to cede land participated in this process. Spending of this relatively small sum of money, compared to programmes to formalise land rights, included six multi-stakeholder meetings and workshops as well as the salaries of three experts, two of whom spent more than two weeks in the village.

Breaking with patriarchal practices

The men in the village played a crucial role in the implementation of this process. Participation reached a tipping point after opinion and customary leaders had been convinced of the proposed mechanism. Many other men followed these first adopters in ceding more secure land use rights to their women within the family farm.

Several factors contributed to encouraging these men to break with patriarchal practices. Awareness raising on the economic benefits of women’s secure access to land contributed greatly to men’s willingness to cede land user rights. GRAF experts invested much time in discussing the role of the woman as an important contributor to the family’s income and well-being with the villagers. During their field stays, they were always available to interact, consult and assuage worries. The bond built by GRAF experts speaking their local language increased men’s trust in this process.

As heads of the family farms, men were able to suggest terms and conditions of the tenure agreements. Typically, most men demanded that women only have these secured land use rights as long as they were part of the family. In case of a divorce, the woman would lose the right to use the land permanently. Granting this first level of control to men and respecting traditional arrangements related to the bond of marriage was important to make men buy into the idea of improving the tenure situation for women. Many men accepted women’s demands for increased surfaces of land, which would allow the latter to produce not only for subsistence use but also for the market.

Finally, the support and endorsement by the municipal administration and customary chiefs played a crucial role in men’s willingness to open up to new ideas of managing and controlling land within the family.

Recognition of land rights through social legitimacy

The voluntarily negotiated intra-household tenure arrangements resulted in a preceding and facilitating document for Rural Land Possessions Certificates, a so-called “Procès Verbal” of a Village Assembly. As such, it is not a legal document but rather an accord validated by the village assembly and recognised by the municipal administration. In case of contestation, the village’s conciliation committee members intervene to mediate disputes.

Issuance of formal land titles to women was neither possible nor desirable within this pilot process. Land titles could not be delivered, as local institutions responsible for issuing land possession documents did not exist in the region the process was being tested in. Building on GRAF’s decade-long professional experience in land governance, tenure arrangements grounded in social legitimacy were privileged in the design of this complementary instrument to the land law. As such, the process was largely led by the village community, and compatible with traditional practices of negotiating and allocating land rights. Furthermore, all tenure agreements were validated and recognised by the village assembly.

Providing villagers with decision-making power over the process and consensus given by the villagers themselves underpinned the legitimacy of these tenure agreements. In other instances, formalisation of land rights is imposed on beneficiaries with much less involvement of customary village authorities. Even where formal papers are available, they do not automatically result in social acceptance within a community, as observed by Saïdou Sanou, founding member of GRAF, who stated: “Someone can have a land title but not be able to exploit the field simply because on the village level the people do not agree with him or her managing this field.”

Looking ahead

GRAF and TMG Research are currently producing a technical guide accompanied by a movie to enable actors to take up the process and apply it in their communities. A recent multi-stakeholder workshop in Ouagadougou has shown strong interest among the National Farmer Confederation, the Ministry of Agriculture and others in implementing this instrument in more villages. As yet, funding commitments are missing, though. This instrument may also be suitable for implementation – in an adjusted manner – in other countries with a similar precarious tenure insecurity situation for women, such as Benin.

Conclusions

The instrument piloted by GRAF and TMG Research to secure women’s access to land is well adapted to socio-cultural conditions in a specific context. Thanks to its resource efficiency and the possibility to implement it in the absence of formal land governance institutions, this instrument offers good prospects for replication and up-scaling. The process of voluntary intra-household tenure arrangements could be perfectly integrated within wider landscape restoration initiatives. Securing land rights for disadvantaged groups and promoting sustainable land management (SLM) practices in an integrated way is crucial in pursuing the principle of “leaving no-one behind”.

Saydou Koudougou is the current Executive Secretary of GRAF. With a Master’s degree in Sociology, he has fifteen years’ experience in research, design and implementation of projects in land tenure and gender and management of agrosylvopastoral resources.

Larissa Stiem-Bhatia currently works at TMG Research gGmbH – Think Tank for Sustainability, based in Berlin, Germany. In the transdisciplinary research project “Soil Protection and Rehabilitation for Food Security”, she co-ordinates research activities in Burkina Faso focusing on gender, land rights and structural hindrances to adoption of technologies for sustainable land management (SLM). She holds a Master’s degree in Environmental Studies and Sustainability Science.

Contact: larissa.stiem-bhatia@tmg-thinktank.com

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment