Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Learning from participatory evaluations

The discussions around rigorous evidence on the impact of development programmes and the use of accurate scientific methods tend to veil the subjectivity of impact evaluations; the moment, the research subject, the methods, the “deliverables” and the participants, both evaluators and evaluated, are the result of intentional multistakeholder decision-making. There is a purpose behind each evaluation, which needs to be outlined in the description of the process and methodology applied of an evaluation. Since impact evaluations are costly investments, donors certainly play a crucial role regarding the type and quality of such exercises.

Helvetas, as a “Learning Organization”, endeavours to strengthen the learning aspect in most of its undertakings, methods and tools, evaluations included. Convinced that learning is, as described by Harold Jarche, an advisor on organisation development, “a continuous process of seeking, sensing, and sharing” and happens through participation, engagement and communication, we support our partners and staff in leveraging their rich and diverse knowledge by fostering critical reflection and exchange. In the field of project or programme evaluations, we therefore explore, promote and apply methods that bring in the knowledge and perspectives of stakeholders at various levels. Some of these are described in the following.

Primary Stakeholder and local institutions – Social Audits and “Beneficiary Assessment”

Social Audit, the assessment of the performance of “duty bearers” – e.g. public services of local governments – carried out by the “right holders”, citizens or users of such services, is an evaluation method that improves “downward” accountability and, finally, the quality of public services. Social Audits as well as Client Satisfaction Surveys are useful learning tools in projects that support local public institutions in discharging their responsibilities in delivering quality public services and respond to citizens’ needs. The strengthening of such participatory and inclusive evaluation practices contributes to creating processes for dialogue between stakeholders that per se are results of development, as we have observed in Eastern Europe and Bangladesh.

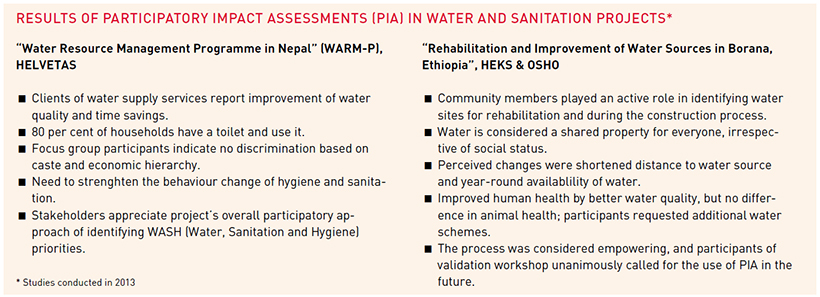

Another approach or methodology which also fosters the empowerment of primary stakeholders is the “Beneficiary Assessment”, as it has been known since its description by then World Bank’s Lawrence Salmen in the 1990ies. It is a qualitative method used to improve the impact of development operations by capturing the views of intended beneficiaries regarding a planned or ongoing intervention. Community members, farmers or other project participants are trained as peer observers in a two- to three-day workshop. They then identify the research questions and enter a process of interviewing peers in their communities. The objective of this method is to assess the value of an activity as perceived by project beneficiaries and to integrate findings into project steering. It is designed specifically to undertake systematic listening of the project participants and other stakeholders by giving voice to their priorities and concerns. This method of systematic consultation is used by project management as a design, monitoring, and evaluation tool. The WARM (Water Resources Management) project in Nepal (see Box below) shows that the nature of Beneficiary Assessment provides the development of peer observer skills, which are appreciated by the participants and communities and can benefit other development processes such as identification and planning of new interventions.

Own staff and partners – peer reviews and “Capitalisations” for knowledge sharing

External assessments of interventions are valuable and indispensable pieces in Project Cycle Management. While final evaluations are usually performed by external collaborators, project Mid-Term Reviews can be conducted without external support by own thematic advisors and involve staff and partner organisations. Although this is a lighter and more flexible process, it often brings valuable findings as participants tend to be more engaged and more critical of their own performance than external evaluators who might need to communicate more cautiously. Moreover, the teams joining a self-assessment exercise gain ownership on the findings, conclusions and recommendations. Their contributions to the procedure translate into stronger commitment towards complying with agreed follow-up actions.

We also endorse processes that bring in stakeholders, professionals, partners and colleagues at different stages for evaluations of highly complex operations or higher-level evaluations, for example for sector- or country programme evaluations. Peer reviews focus on the facilitation of such endeavours and bring the people together, be it face-to-face and synchronous or at distance and nonsynchronous. The multiple perspectives and expertise of involved individuals and the numerous insights and opinions enrich such evaluations and foment learning among peers; this is a moment of intense knowledge sharing. Bringing together and showcasing the experiences of all colleagues participating in bio-cotton-projects (see Rural 21 no 2/2017) or interventions that focus on building up Rural Advisory Services offers learning opportunities for one’s own and many other organisations.

The Review of Country Strategies can bring in the valuable knowledge of many colleagues when facilitated in a participatory way. Country directors and thematic experts from neighbouring countries can contribute to analysing the progress of a country programme, and learning takes place at various levels and on ‘both sides’, evaluators and evaluated. This benefits mutual inter-organisational learning, the sense of belonging to one organisation as well as the regional focus of collaboration, as we have seen for example in Central Asia.

Another promising evaluation procedure after finalising longer interventions is the Capitalisation of Experience (CAPEX), which allows to gather and systematise all relevant project documents and collecting of insights from participants and external key informants on good practices, failures and lessons learned, as we recently did for our engagement in Bhutan’s Community Forestry Sector. CAPEX publications are important sources of information for strategic decision-making as well as for interested persons in the sector and the region alike. They are shared on relevant platforms and networks and are useful “certificates” for staff to show their career and expertise to others.

Looking ahead

Internationally, there is a trend to professionalise evaluations and to put the decision on design, methods, indicators and measurement into hands of the academia. The interaction of NGOs with research institutions to understand impact is a very welcomed and fertile evolution. Scientific research in development projects is a complementary procedure of participatory methods, and not a substitute. Given its high costs and tardy results, rigorous assessments are exceptional studies that should be conducted regularly and well-planned in selected projects. But development organisations need information on impact of all their projects, at early stages of implementation and in a useful format for decision-makers in the countries.

Helvetas’ M&E strategy for improving result orientation and impact is to build up capacities for better evaluation in the teams that perform regular project M&E through training and coaching; to lift their attention from activities and expenditures to outcome and impact through improving reporting; to improve indicator selection and measurement methods at the very beginning of a project; and to make M&E slimmer and more useful. Finally, development organisations are also accountable for spending on M&E and impact assessments, which need to be justified by their usefulness for learning and steering, improving future actions and developing capacities in the countries. We therefore strive to mix methods and evaluation designs, to adapt the evaluation process and participants to the context and specific situation of the project and to be flexible and innovative with applied methodologies. The critical analysis of the “evaluability” of a project, the participatory process of defining methodology and timing, and the involvement of staff and partner organisations in impact evaluations contribute to capacity development, empowerment and learning.

Kai Schrader is advisor for Evaluation & Learning at HELVETAS Swiss Intercooperation. Having worked in development co-operation for over 20 years, he has focused his activities on participatory methods for planning and evaluation, rural development, and topics related to land use, agriculture, and ecology. Kai Schrader holds a PhD from the Centre for Development and Environment of the University of Berne.

Contact: kai.schrader@helvetas.org

WHAT ABOUT EVALUABILITY?

All considerations regarding the right design of an evaluation aside, one aspect that must not be forgotten is evaluability, i.e. “the extent to which an activity or project can be evaluated in a reliable and credible fashion”, as defined by the Development Assistance Committee of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD-DAC).

While an evaluation aims to judge the merits of a particular intervention, an evaluability assessment occurs before an evaluation. It can support formulating a recommendation on whether an evaluation is worthwhile in terms of its likely benefits, consequences and costs. Also, it can show at which point the evaluation should take place and help decide whether a programme or intervention needs to be modified, whether it should go ahead, or whether it should be stopped. Assessing the evaluability of a measure can prevent wasting valuable time and resources on a premature or inappropriately designed evaluation. And, as a WorldBank Group blog explains, it can “thwart ‘evaluitis’ and the ‘ritualization’ of evaluation processes”.

The Overseas Development Institute (ODI – UK) authors of the manual “Evaluability Assessment for Impact Evaluation” maintain that three focus areas ought to be covered by an evaluabiltiy assessment:

- the adequacy of the intervention design for what it is trying to achieve,

- the conduciveness of the institutional context to support an appropriate evaluation, and

- the availability and quality of information to be used in the evaluation.

The guide contains a checklist to help evaluators to answer the following key questions:

1. Is it plausible to expect impact? This is where the adequacy of the intervention design is examined. Do stakeholders share an understanding of how the intervention operates? Are there logical links between activities and intended impact?

2. Would an impact evaluation be useful and used? Here, the focus is on stakeholders, demand and purposes. Are there specific needs that the impact assessment will satisfy, and can it be designed to meet needs and expectations?

3. Is it feasible to assess or measure impact? This question refers to data availability and quality. Is it possible to measure the intended impact, given on-the-ground realities and evaluation resources available?

The manual is available for downloading on the ODI website: www.odi.org. Useful information on evaluability can also be found on the BetterEvaluation project website: www.betterevaluation.org

(sri)

References and further reading:

Helvetas Blog: "'Learning expedition' with 15 projects on monitoring and results measurement"

Helvetas Decentralization and Local Development (dldp) Program, Albania

Helvetas Local Governance Programme Sharique

Schrader, Kai (2014), Saving time and improving Health. Impact Assessment.

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment