Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Can development co-operation help reduce international labour migration?

Fluchtursachenbekämpfung is a controversial topic. Opposition parties argue that governments refer to the causes of migration to detract attention from their failure to manage the refugee crisis. Critics of development cooperation ask why so many people are still trying to find a future for themselves outside their home areas. Supporters of migration fear that Official Development Assistance (ODA) could be misused for building walls against migrants. Migration researchers object that more effective efforts to reduce poverty will even stimulate international migration as the very poor cannot afford to migrate. Some development co-operation practitioners fear that reorienting aid towards migration policy aims will just end up as another re-labelling exercise.

So, the question this article explores is whether and by what means development co-operation can mitigate the causes of migration. The focus here is on labour migration, rather than refugees, acknowledging that it is not always possible to clearly separate one from the other. Another focus is on interventions addressing the situation in regions of origin, rather than on those aiming at better migration management. And lastly, there is a certain focus on sub-Saharan Africa, as it is our neighbour continent that most of the funds are supposed to go to.

WHAT INFLUENCES LABOUR MIGRATION?

Migration theory tends to explain migration streams by distinguishing between push factors (conditions in the region of origin), pull factors (conditions in the region of destination) and migration costs. Although somewhat simplistic (see Figure on the right), this model can help structure the analysis of influencing factors. While Fluchtursachenbekämpfung relates to the push factors, migration costs also tend to play a role. Push factors for labour migration can be analysed from a macro- and a micro-perspective.

The push factors: jobless growth, …

A macro-economic analysis of global labour markets indicates that the phenomenon of “job-less growth”, well-known to most countries in the Global South, tends to foster migration in search of job opportunities. While economic globalisation has stimulated international trade and economic growth rates, it has failed to increase global employment, as it has been accompanied by labour-replacing technological progress. New jobs created by economic growth are matched by the destruction of jobs through automation. While this is a world-wide phenomenon, the impacts on different regions differ greatly. Less competitive regions are the losers. In sub-Saharan Africa, an additional 15 million young people reach working age each year, set against two million additional jobs. This mismatch has been observed even in periods of high economic growth rates of five to ten per cent per annum. The global nature of the mechanisms causing unemployment indicates that there are limitations for development co-operation when it comes to addressing the root causes of labour migration.

A macro-economic analysis of global labour markets indicates that the phenomenon of “job-less growth”, well-known to most countries in the Global South, tends to foster migration in search of job opportunities. While economic globalisation has stimulated international trade and economic growth rates, it has failed to increase global employment, as it has been accompanied by labour-replacing technological progress. New jobs created by economic growth are matched by the destruction of jobs through automation. While this is a world-wide phenomenon, the impacts on different regions differ greatly. Less competitive regions are the losers. In sub-Saharan Africa, an additional 15 million young people reach working age each year, set against two million additional jobs. This mismatch has been observed even in periods of high economic growth rates of five to ten per cent per annum. The global nature of the mechanisms causing unemployment indicates that there are limitations for development co-operation when it comes to addressing the root causes of labour migration.

Looking at the micro-perspective, we see a corresponding picture. The majority of African families are securing their living through migration. More than 50 per cent of rural households and around 70 per cent of urban residents in sub-Saharan Africa are part of translocal livelihood systems, according to a recent analysis of a wide range of case studies by Malte Steinbrink and Hannah Niedenführ. For approximately 50 million rural-based African households, migration of at least one member, mostly young men, has become an economic necessity, as neither rural income sources in the home region nor incomes in the areas of destination can ensure a secure and decent living. So migration of young people is not merely an individual decision indicating a preference for an urban lifestyle. Rather, it forms a well-established part of rural-urban livelihood systems. Most of the migrants are temporary migrants, who maintain social, cultural and economic links to their home areas (see the article by Einhard Schmidt-Kallert in Rural 21 02/2016). Some migrate on a seasonal basis, some return once a year for festive seasons, some are circular migrants, and others migrate for a certain period of their lifecycle, intending to return after they have saved enough money to get married and establish a farmstead. Where migration has become a deeply rooted part of risk minimising livelihood systems, it will not be easy for development co-operation to provide sufficiently attractive alternatives.

… population growth, …

Where too many young people are entering the labour market compared to available job opportunities, population growth cannot be ignored as a push factor. Indeed, sub-Saharan Africa still has a population growth rate of 2.5 per cent per year – far above that of other world regions. This figure, however, needs to be assessed in relation to the low population density of 45 people per sq. km (Germany: 230), which still leaves wide regions with underutilised resource potentials, but also with long distances to be overcome and correspondingly high costs for infrastructure development. The major obstacle to successfully addressing the high population growth rate within a short period is the underlying rationale of “demographic transition”, according to which a reduction in the fertility rate tends to follow a reduction in the mortality rate with a time lag of roughly one generation. This means that people are generally only prepared to reduce the number of children they have by means of birth control after they have seen for themselves that most of the children being born survive. Africa has only achieved a significant reduction in the mortality rate during the last decade (after a sharp interruption caused by HIV/ Aids in the 1990s). So, the reduction in fertility rates has started just recently. While family planning support can help speed up this process, there will be a delay until birth rates are affected due to the increasing number of women in the birth-giving age group. Thus, the scope for reducing migration via population policies is severely limited as well.

… environmental conditions

Another push factor is deteriorating environmental conditions such as climate change, soil deterioration or increasing water scarcity. In Africa’s Sahel region, for instance, migration has become a widespread response to droughts and food crises. While environmental migration is frequently emphasised in support of climate policy, research results indicate that environmental push factors are usually only one among a whole set including agricultural markets or increasing scarcity of land. While effective climate change mitigation and adaptation policies are crucial to reducing migration pressure in the long run, their short-term impact on migration is limited.

Looking at these push factors in context, we can conclude that while development co-operation does relate to all of them, it clearly cannot easily influence most of them in the short run.

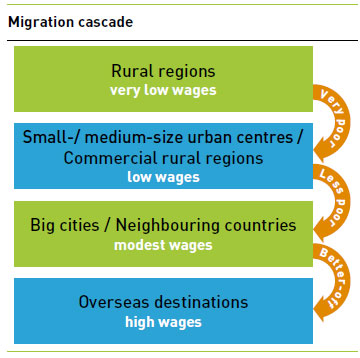

Role of migration costs reflected by migration cascade

Migration costs are an impeding factor in particular for long-distance international migration. There appears to be a clear correlation between the income levels of households and the distance of migration. In Nepal, for example, the poorest in a village look for jobs in rural areas, the less poor can afford to migrate to Kathmandu, the middle strata tend to establish migration networks to Indian destinations, while only migrants from the more well-to-do farm households manage to find jobs in the Arab Gulf states. So, the jobs on the construction sites in Qatar, considered terrible from our human rights perspective, are among the most attractive destinations for Nepali villagers. Such migration barriers only allow the comparatively better-off people to get to Europe. That is why some experts warn that more successful efforts towards poverty reduction might enable more people to venture on the costly journey to Europe – poverty reduction as a springboard for international migration. This argument does not stand the test of a more in-depth analysis, however. In fact, migration often takes place in stages. Poor people from rural regions migrate to regional urban centres; people who have accumulated a bit of income and experience there may move on to big agglomerations. More advanced migrants from those cities may be able to afford the step to more prosperous countries, if competition from the new arrivals in urban labour markets or in informal service sectors becomes too stiff. Accordingly, there is an international hierarchy of destinations within the African migration pattern. While people from Burkina Faso may go to Ghana, Ghanaians tend to go to Nigeria, and Nigerians seek their fortune in South Africa or in Europe. So migration pressure from poor rural regions is passed on to better-off people in urban centres who have the capacity to migrate overseas. We can call this a migration cascade (see Figure). The resulting message for development policies is that by reducing the migration pressure at all levels, poverty reduction in the rural regions of origin can help reduce international migration.

This argument does not stand the test of a more in-depth analysis, however. In fact, migration often takes place in stages. Poor people from rural regions migrate to regional urban centres; people who have accumulated a bit of income and experience there may move on to big agglomerations. More advanced migrants from those cities may be able to afford the step to more prosperous countries, if competition from the new arrivals in urban labour markets or in informal service sectors becomes too stiff. Accordingly, there is an international hierarchy of destinations within the African migration pattern. While people from Burkina Faso may go to Ghana, Ghanaians tend to go to Nigeria, and Nigerians seek their fortune in South Africa or in Europe. So migration pressure from poor rural regions is passed on to better-off people in urban centres who have the capacity to migrate overseas. We can call this a migration cascade (see Figure). The resulting message for development policies is that by reducing the migration pressure at all levels, poverty reduction in the rural regions of origin can help reduce international migration.

What has development co-operation contributed so far?

First, we have to acknowledge that there is little statistical evidence for the impact of development co-operation interventions on migration. It is obvious that out-migration from rural areas has increased. But it is hard to say whether this is despite successful rural development efforts or due to neglect of rural areas during the past two decades or is even a result of rural interventions. The phenomenon of translocal rural-urban livelihoods is known from dynamic and from marginal rural regions. Ongoing efforts towards placing “jobs, jobs, jobs” at the top of the agenda of development co-operation with Africa indicate that past efforts were too limited or not very successful. The major achievements in reducing income poverty during the last five decades were made in countries like China and South Korea. They were based on macro-economic policies with minimum contribution from international development co-operation. Trade policies played a major role in the initial phases. Examples from Zambia and Nepal may indicate the potentials and limitations of rural development programmes in reducing out-migration from rural regions. In Zambia, significant donor-supported efforts were made towards rural development during the 1980s, with the aim of explicitly reducing out-migration in support of the Government’s “go back to the land” campaign.

Rural development can reduce migration pressure. But only to a limited extent.

These efforts were followed by a clear trend of remigration to rural regions, which also resulted from a change in terms of trade between agricultural versus industrial products, i.e. a marked increase in producer and consumer prices for agricultural products. While trade policies provided necessary incentives for returning to the land, development programmes provided the opportunities and capabilities. In Nepalese hill areas, such programmes helped strengthen translocal livelihood systems by improving the income basis of migrants’ wives through promoting horticulture rather than by seeking to offer local opportunities to the migrating men. This was a reflection of the limited natural resource potentials and high land pressure. The examples show that rural development interventions can improve income opportunities if accompanied by favourable market conditions for rural products. In doing so, they can reduce migration pressure among the rural poor but are unable to replace income from migration.

Taking the limitations of global labour markets and the phenomenon of “job-less growth” in Africa – in association with limited and mostly marginal income opportunities in non-agricultural sectors – into account, development co-operation needs to be aimed at reducing migration pressures in rural and in urban regions. It has to focus on creating jobs and income opportunities, both for the youth and for all other job seekers. Broad-based, inclusive income generation is the key towards mitigating migration pressure. What can be done to contribute to that goal under the prevailing economic environment in African countries?

As development policies not only have the potential to reduce but also run the risk of intensifying migration pressure, the first set of recommendations follows the principles of doing no harm and leaving no one behind. Interventions need to avoid destroying jobs and income opportunities by avoiding labour-saving forms of technical progress. They have to avoid displacement of small-scale farmers or herders by large-scale land investors. They should avoid supporting the setting of inappropriate product-related standards that tend to exclude resource poor producers. They should not be guided by rural transformation models following the principle “grow or give way”.

Ten rules for migration sensitive interventions

Doing no harm is not enough, however. So what else needs to be done to promote inclusive job and income promotion taking the adverse competitive conditions of sub-Saharan countries into account? Ten rules have to be considered. First and foremost, jobs are only created by those investments that generate a positive net employment effect. Many private investments tend to destroy more jobs or income opportunities than they create. Investment promotion therefore needs to focus on new, innovative economic activities which replace imports or add processing steps to value chains rather than on replacing existing local activities. Second, economic opportunities have to be analysed with regard to the competitive environment. There are usually pro-poor, i.e. labour-intensive opportunities with a good chance of becoming competitive, although some effort may be required to identify them via a proper analysis of markets and local resources. Third, this calls for a thorough analysis of the – often underestimated – potentials of the poor in order to maximise their inclusion in the labour and commodity markets. Fourth, small-scale producers need to be organised in socially inclusive producer organisations to qualify for joint access to services and markets – a prerequisite for their access to income opportunities. Fifth, the promotion of appropriate technologies has to follow the guideline “as labour-intensive as possible while as efficient as necessary”. Any promotion of “technical progress” per se will intensify migration pressure. On the other hand, productivity often needs to be increased in order to overcome labour bottlenecks or to become competitive. A tractor can replace 20 labourers in one case or help create 20 jobs in another. At any rate, the employment effect of technological change needs to be given the utmost attention. Sixth, trade policies need to be adjusted in order to protect promising labour-intensive trades. Seventh, land reforms have to ensure that poorer smallholders cannot be impelled to sell their land in the event of an emergency. Eighth, socially inclusive promotion of natural resource management – including soil rehabilitation and climate change adaptation – is essential to prevent environmental migration. Ninth, labour-intensive public work schemes for establishing and maintaining infrastructure should be promoted. This can help to improve seasonal job opportunities on a broad scale in the short run. Last but not least, skills development should focus on fields related to existing income opportunities. Training in other areas will stimulate rather than reduce migration.

We can conclude that rural development efforts can contribute to Fluchtursachenbekämpfung if oriented towards creating a positive net-employment effect within and outside agriculture and if accompanied by targeted trade policy adjustments. Such rural development contributions are necessary but will most likely not create sufficient jobs. This can only be achieved in a different global and national macro-policy environment.

Dr Theo Rauch is Visiting Professor at the Center for Development Studies / Geographical Department of Free University of Berlin. He has been engaged in rural development research and practice in African and Asian countries for over 40 years.

Contact: theorauch(at)gmx.de

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment