Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Child labour: an Ethiopian perspective

In 2012, about 168 million children world-wide were child labourers, a one third decline since 2000 (ILO, 2006, 2013). Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest incidence of child labour, with about 21.4 per cent of the children being put to work (ILO, 2013). Estimates also indicate that almost 60 per cent of the global child labour takes place in the agriculture sector, where the lives of about 100 million children are affected (FAO, 2015; ILO, 2013). Various studies argue that child labour can harm the physical development and health of children and jeopardise their human capital formation. This situation may also lead to a cycle of poverty and precarious employment in later life. Other studies claim that, on the contrary, child labour might bring more resources into the family and thus improve child nutrition and schooling. We examined the effects of childhood work among four to fourteen-year-olds in rural Ethiopia, looking at these practices in 1999/2000 and their impact on human capital formation (grade attainment) during childhood and on earnings 15 years later, in 2015/2016.

The baseline survey (1999/2000) shows that Ethiopian rural children widely participated in various low-intensity activities such as cattle herding and domestic chores, but also to some extent in physically demanding jobs, especially on family farms. We found that widespread child labour practices in rural Ethiopia are coupled with low levels of school participation, making it one of the most critical development issues of the country. The findings showed that while about three-quarters of children participated in some forms of work, only a third of children were attending school. Over half of the children in the households surveyed were working exclusively as labourers. Looking at gender differences, we found that the children who participated in productive activities such as farming and herding or non-farm activities were mainly boys, working on average about 30 hours per week, while girls were by far more likely to perform domestic chores, so-called non-productive activities, working about 13 hours per week.

Child labour and grade attainment

Our econometric analyses reveal that work in childhood is likely to affect both children’s grade attainment and their earnings as adults, but there are variations in the thresholds at which working becomes detrimental, from both short- and long-term perspectives. The short-term effects show that work in childhood could even improve children’s grade attainment. There is, however, a trade-off between working and grade attainment, which is likely to occur after about 24 hours of work per week. Beyond these threshold points, each extra hour of work is significantly associated with diminishing grade attainment. But as long as children worked below this cut-off level, they could actually improve their expected grade attainment by about 3.1 per cent for each extra hour of work. Given that, on average, children worked around 22 hours per week, it follows that they could have worked two more hours per week and, other things remaining constant, increased their expected grade attainment by about 6.2 per cent, raising their overall grade attainment from 18.8 per cent of attainment expected at their ages to 25 per cent. The associations between childhood work and grade attainment do, however, vary in accordance with the types of childhood work – domestic chores and farming activities.

Child labour, education and adult labour market outcomes

However, appropriate policy measures to reduce the detrimental effects of child labour, when work exceeds the cut-off point, on early human capital formation (grade attainment) should also take account of the labour market outcomes, such as earnings when adults, that result from labour in childhood. Through the follow-up survey, conducted 15 years later, we could track the children’s progress, and found that, on average, they earned Birr 7,145 (around 357 US dollars) per annum, but females earned three times less than the average earnings of males. The data also revealed that childhood education was generally associated with higher levels of earnings in adulthood, except in domestic chores, family labour working and studying.

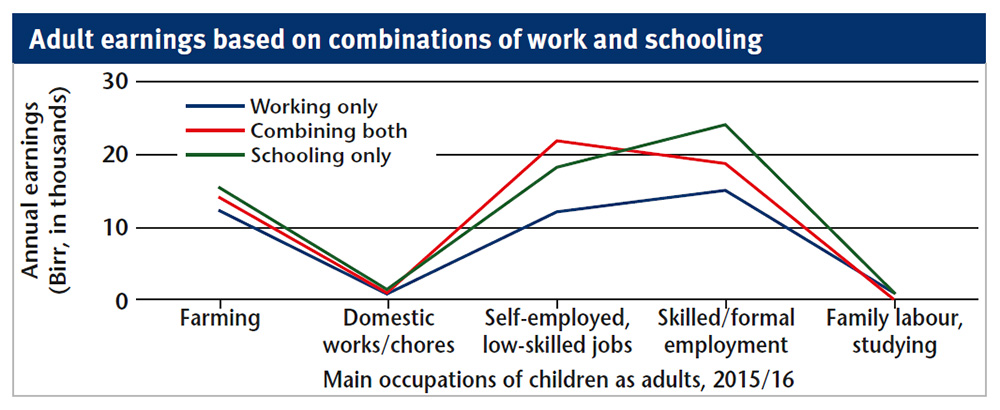

On the other hand, work-only children earned consistently less than their peers in all productive economic activities (see Figure below). This strongly suggests that exclusive child labour could significantly reduce the individual’s later earnings potential in the adult labour markets.

Earnings and occupational trajectories

Using the same dataset, the econometric analysis of the associations between childhood work-school combinations and earnings reaffirms that, compared to exclusive childhood labour, both exclusive schooling and schooling combined with work are significantly associated with higher earnings. Specifically, children exclusively attending school and those combining work and school had 42 and 57 per cent higher adulthood earnings, respectively, than their peers who only worked. A number of factors may explain the stronger earning benefits of combining work with school, rather than only receiving schooling. Possible explanations are: the types of current occupations and the nature of adult labour markets with regard to skill requirements; the likelihood of acquiring relevant (transferable and marketable) skills from childhood work experience and hence the potential synergies between working and schooling.

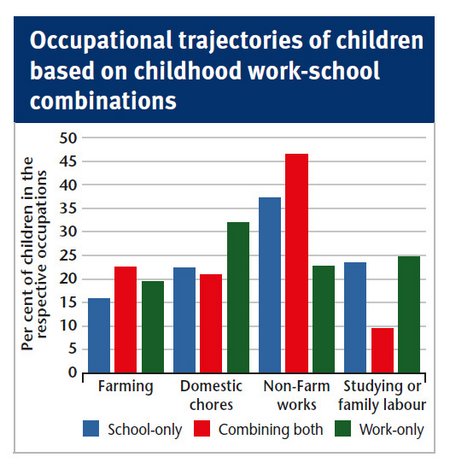

With regard to occupational trajectories (see Figure), we found that while about half of the multi-taskers and around 38 per cent of school-only children are now working in non-farm jobs (formal or informal), about a third of the work-only children are now domestic workers, including housewives.

With regard to occupational trajectories (see Figure), we found that while about half of the multi-taskers and around 38 per cent of school-only children are now working in non-farm jobs (formal or informal), about a third of the work-only children are now domestic workers, including housewives.

A potential synergy between work and schooling in childhood was noted for those who subsequently worked in the non-farm low-skill jobs and developed certain entrepreneurial skills. Indeed, most of the experiences and skills acquired from childhood work can more likely be used in low-skill jobs. This means that human capital policies that limit children’s work participation or completely eliminate child labour may diminish these learning avenues, which is why alternative skill-learning opportunities should be made available as children become adults. However, when it comes to formal, high-skill jobs, the school-only children now working in these positions tend to be higher earners than their multi-task peers. This suggests that when work is combined with schooling, it can also have negative effects on schooling and result in lower earnings. But as mentioned above, these effects seem to be limited to the formal job market. So, there are work-school interactions here that need to be considered when rethinking assertions about child labour and policy measures against it.

We also examined the effects of childhood work on earnings using the intensity of work as our variable, i.e. the number of hours worked per week as a child. Results show that childhood work, in general, could boost adulthood earnings by about 10.7 per cent for children overall and by about 8 per cent for split-off children, i.e. children who have formed their own families and independently engaged in the adult labour markets during the follow-up study. However, the likely trade-off between childhood work and earnings was observed at around 22–23 hours of work per week, at a slightly fewer number of hours than the trade-off point between working and grade attainment.

The study found that the negative returns of earnings from childhood grade attainment was contradicting established human capital theories. This points to the poor quality of child education in rural Ethiopia, on the one hand, and also to the low importance placed on formal childhood education in certain adult labour markets, on the other. In this regard, although it is well known that educated workers are more productive, thanks to the skills acquired through learning, our finding implies that there could also be a reversal effect: in some cases child education does not lead to higher adult earnings due to the inherent nature of occupations such as traditional farming and the functioning of adult labour markets. Indeed, the follow-up survey showed that children from the baseline study had very low levels of grade attainment (18.8 percent) compared to what would be expected of their age-groups, suggesting its negligible potential to boost earnings later in life. This is a critical policy issue for the country, which is striving to achieve structural transformation in its economy, reduce poverty by raising household incomes, and achieve food security through increasing productivity. Understanding the ways in which working as children can shape people and thus determine adult earnings is another critical issue for human capital policy-making. We identified cognitive skills formation (the ability to read and write) as one of the potential pathways through which childhood work affects earnings over time. The data shows that cognitive skills have positive and statistically significant effects on earnings, depending on the hours worked in childhood. Particularly, significant effects of cognitive skills on earnings were found among multi-task children, male children and children from wealthier households.

The findings on the effects of cognitive skills on earnings depending on the hours worked reaffirm our earlier insight that children who combined work with schooling were able to raise their adulthood earnings compared to their peers who were either exclusively working or exclusively attending school. In our view, combining childhood work with schooling might help children to develop entrepreneurial and occupation-specific skills and augment their ability to easily shift to productive jobs as adults. On the other hand, those who continue working as adults in jobs similar to their childhood tasks showed a negative association with adulthood earnings. This trend is particularly strong amongst girls, possibly due to the nature of female roles as adults, with most girls surveyed becoming housewives, and partly due to a lack of transferrable and marketable skills acquired from their childhood chores.

Key messages

Our findings suggest that childhood work, mainly when it is combined with schooling, can facilitate early human capital formation and can boost the earnings of children when adults. However, the results also indicate that exclusive childhood work is likely to compromise the earning potentials of children as adults. These results therefore imply that developing countries need to incorporate an appropriate policy mix in their human capital development strategies. Governments should link early human capital policies with policies targeted specifically at youth and adults. For example, compulsory child education could be combined with conditional cash transfer and school feeding programmes, and with positive incentives such as parental recognition of a child’s specific skill attainments. These interventions, however, have to be accompanied and sustained by consistent youth and adult-targeted human capital policies, including technical and skills training, to keep up with the technical changes in the economy. Moreover, policies that limit children’s participation in work and promote schooling should be supported by a social capital approach to skills building and entrepreneurial training in adulthood.

Essa C. Mussa, Alisher Mirzabaev

Center for Development Research (ZEF)

University of Bonn, Germany

Assefa Admassie

Ethiopian Economics Association (EEA)

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Contact: essa.chanie@uni-bonn.de

References

- FAO. (2015). Handbook for monitoring and evaluation of child labour in agriculture: measuring the impacts of agricultural and food security programmes on child labour in family-based agriculture. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization.

- ILO. (2006). Facts on Child Labour. International Labour Organization, Department of Communication and Public Information, Switzerland.

- ILO. (2013). Global estimates and trends of child labour 2000-2012. International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour (IPEC).

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment