Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

African youth bring innovations to farming

Despite the growing demand for food that offers a huge employment potential within the agricultural sector, young people in sub-Saharan Africa are leaving rural areas. To them farming clearly is not attractive under the present conditions. At the same time, agricultural research has developed many technologies with proven potential benefits, and these innovations are set to play a key role in meeting food demand and increasing income in rural areas. But adoption rates and impact remain low due to e.g. lack of awareness and skills, difficult access to agricultural inputs and absence of required professional services. New technologies need an enabling environment with a better business and investment climate. The development of this enabling environment could offer the youth job opportunities – far more than farming itself. But how will young people gain the necessary professional skills and experience and develop their professional network to truly become key assets for transforming Africa’s rural development?

A three-phased strategy

Our team at AfricaRice works with young underemployed people in Benin. Within the project ‘Innovation Transfer into Agriculture – Adaptation to Climate Change’ and the One World – No Hunger initiative, we use a three-phased strategy to help young people to develop their professional skills and to find their niche in the agricultural sector. First, we validate and improve their applicable agricultural knowledge via e-learning, second, we give them the opportunity to become part of a professional network and gather professional experience on the ground, and third, we assist them in creating their business or finding a job. The process is driven by a result-oriented business model, enabled by a large network and facilitated by a range of ICT solutions, as explained below.

A rural professional network. Since 2016, we have collaborated with extension services, farmers’ organisations and a team of experienced national experts to build a large network of farmers’ groups and national and international agricultural value chain experts. The network involves 21 districts of Benin, covering about a third of the country. At the beginning, local partners helped to identify two field agents per district who collected comprehensive data and information on local agriculture, and created websites for their district. They worked on a question-and-answer service with farmers and experts in order to identify production constraints and potential solutions. Via village meetings, they extended the network to 1,500 groups of farmers and processors, connecting over 30,000 individuals living in 173 municipalities. The field agents also set up an office in each district that provides a space for collaboration, information sharing and dialogue. Provided with Internet access, a printer, a digital camera, computers and a collection of practical guides on good and innovative agricultural practices, this hub connects the district to the outer world. These offices form the entry point for young professionals wishing to engage in the agricultural sector.

A results-based business model. To achieve financial and institutional sustainability and to facilitate scaling of innovative practices, we adopted an innovative business model that drives the process, the so-called Rural Universe Network model, which engages local collaborators as freelance service providers. Within the model, services are designed with input from national experts such as retired scientists who have a wealth of knowledge and experience. Services are clearly defined as small pieces of work with a time-frame and a specific output. A service might be the response to a question from a farmer, an e-learning course or an inventory of farmers’ groups. Services can also be made up of several tasks linking people with complementary skills. Each service provider is in charge of a specific task depending on his professional and social skills. Service prices are based on prices in the local economy. Service providers are paid upon delivery, and if the quality of their service is satisfactory. If not, we give them feedback and continue to work with them until the task has been completed. People can engage on a part-time basis, which allows them to pursue other activities. A key advantage of the model is that it does not build a parallel structure but collaborates with organisations that are present locally, strengthening them in the process. Most importantly, this system allows us to engage young people as service providers. For many it is a unique opportunity to gather professional experience.

Youth-tailored ICT solutions. Our whole network is interconnected through low-cost and easy-to-use information and communication systems. The 21 district offices have Internet access via a mobile router. We use a Wiki for team collaboration, dialogue and documentation of the entire process. It is a customised platform for producing, delivering and managing e-learning courses and a mobile phone corporate network within which calls are free. There is also a vast repository of production constraints and corresponding solutions that resulted from the question-and-answer service, a system that monitors the status of service delivery, and Mobile money is used for payment.

This dynamic and lively platform allows the young people to connect and exchange not only with extension agents and national experts, but also with each other, which has proved to be very valuable in accelerating learning and problem solving.

Fostering applicable knowledge. To foster the agricultural knowledge of young people, we offer e-learning courses through the online platform Moodle. We provide courses on basic agricultural knowledge, technologies, entrepreneurship and extension skills (the e-learning approach is described in a companion article “E-learning courses made in West Africa, for African youth”). Initially, courses on basic agronomic knowledge were made available to Agricultural Technical College graduates. We are now releasing more advanced courses.

How youth accelerate the innovation process

From the 250 graduates who successfully studied e-learning courses in 2016, 111 were selected as service providers for a period of eight months. Each of them assists three groups of producers or processors to test innovative agricultural practices. We cover seven value chains, including production and processing of rice, maize, soya, groundnut, cassava, shea nut, cashew nut, palm oil and poultry.

These young professionals can gain experience, develop their professional network and learn from farmers. Part of their job is to cope with unforeseen problems and to document the process in order to provide feedback to research. The producers get a chance to test new technologies in otherwise risk-averse environments. The young professionals team up with local young farmers, who are members of the collaborating farmers’ groups and left school early but are literate. This collaboration is crucial as the young farmers have local knowledge, are trusted by their group and can help in day-to-day monitoring. Throughout the eight-month period, the young professionals are coached by the experienced field agents in the district.

As poverty is one of the main factors hindering technology adoption, we invest in the innovation process and development of financial capital. At the end of the season, farmers’ groups will sell the produce that they grew on their experimental field or that they transformed in the improved processing unit. This money will be used to establish an autonomous micro-credit system, which field agents at the district office will help to manage. The young professionals are encouraged to save part of their income earned as service providers during the eight-month period. Savings will help them to develop their own business. Farmers’ groups and district teams assess the potential of technologies for growth and identify business opportunities, in farming or processing but also in the trade and service sectors. Towards the end of the farming season, young professionals and farmers’ groups develop business plans around their ideas. Alongside farming and processing, areas of particular interests include seed production, agricultural inputs, provision of mechanical services and marketing.

The team at AfricaRice are presently designing a package of business development services with experts. In 2018, the project will support promising business proposals during their start-up phase, e.g. with e-learning modules on business development, face-to-face coaching on entrepreneurship and other services that help create a better business environment and investment climate.

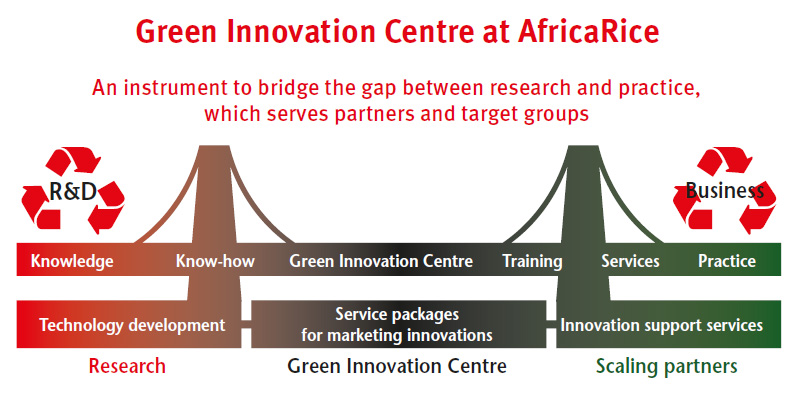

The projects are supported by the GIZ programmes ‘Innovation Transfer into Agriculture – Adaptation to Climate Change’, financed by the ‘Energy and Climate Fund’ and the ‘Green Innovation Centres for the Agriculture and Food Sector in Benin’ within the special initiative ‘One World – No Hunger’, on behalf of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ).

For more information, please visit:

https://wiki.africarice.net

http://elearning.afris.org

http://www.runetwork.org

Marc Bernard, Bruno Tran & Sandra Fürst

Green innovation centre for the agriculture and food sector AfricaRice

Cotonou, Benin

Contact: M.Bernard(at)cgiar.org

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment