Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Organic and Fairtrade cotton – a way out of rural poverty?

Helvetas set up its first organic and Fairtrade (O&FT) cotton value chain project in Mali in 2002, followed by projects in Burkina Faso, Kyrgyzstan, Benin and Tajikistan. Despite the diverse contexts, a majority of conventional cotton farmers faced similar challenges in these countries: Long-term monoculture and exaggerated use of subsidised chemicals led to health problems, depleted soils, and thus reduced yields. In many places, the low yields and volatile cotton world price resulted in negative gross margins and increased indebtedness of farmers. Despite the low profitability of conventional cotton, constricting policies and a lack of experiences in other cash crop production and alternative markets made farmers stick to cotton production.

In this context, organic agriculture offered a way out of indebtedness and increasing health problems of the farming families by providing an alternative production method doing without expensive and harmful chemical inputs, as well as by offering premium sales prices.

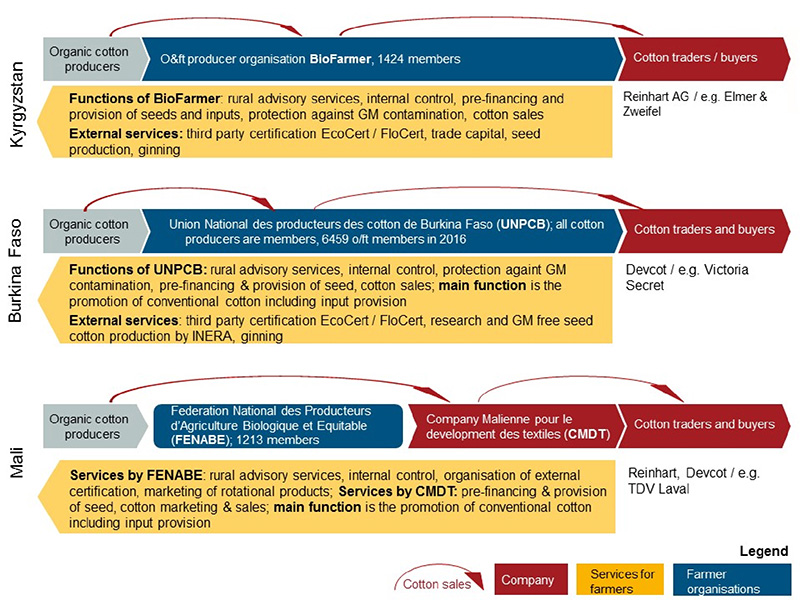

Since the concept of certified organic and Fairtrade products was new in these countries at that time, the projects focused on developing competences of producer organisations and external service providers to offer relevant services, such as rural advisory on organic production, supply of production inputs applicable in organic, the organisation of internal control and external certification, and marketing of certified crops (for the organisational structures of the three value chains and the services that the producer organisations offer themselves or buy from external service providers, see Figure below).

Impact of the organic and Fairtrade cotton value chains

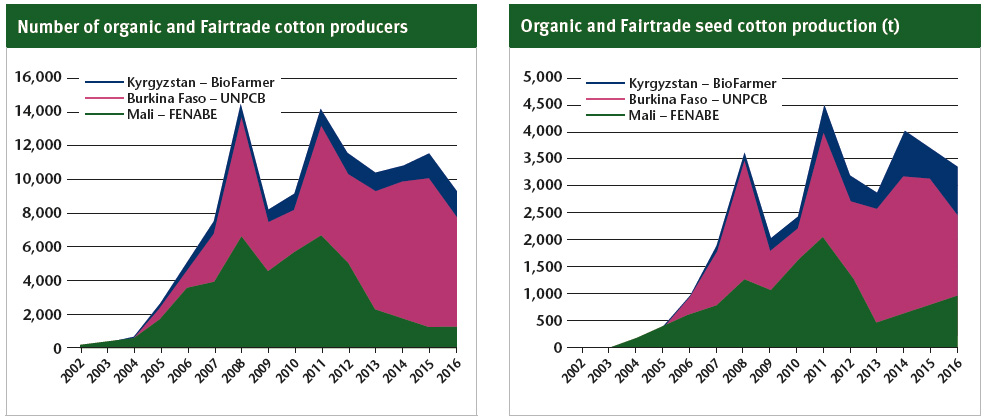

By 2016, there were around 12,000 cotton farmers. However, both their numbers and harvest yield fluctuated considerably. On average, 9,007 farmers produced 2,621 tonnes of seed cotton annually plus rotation crops such as sesame and vegetables. This accounts for a total of 33,200 t O&FT seed cotton, or 291 kg of sold seed cotton per farmer and year. Assuming that farmers participated in the value chain for five years on average, more than 22,000 farm families benefited from the O&FT production. The fluctuating number of farmers (see also left Figure) reflects the serious challenges the organic value chains faced:

In Burkina Faso, Monsanto and the national cotton companies introduced genetically modified (GM) cotton on around 70 per cent of the productive cotton lands in 2008/09. The consequences and costs for the O&FT value chain were manifold: The first contamination of organic cotton in 2009 led to a wide de-certification of organic fields. In order to prevent further GMO contamination of organic cotton, the producer organisation UNPCB had to cease collaboration with farmers in these areas and shift organic cotton production to less fertile areas. Additional investments in the training of the new farmers were necessary. Transportation costs from the new areas to the ginneries were comparably high. Now that GM cotton seeds were available, the seed farms no longer bred local varieties at scale, and the farmers’ cotton seeds for replication were mixed up with GM seeds. Therefore, in the subsequent years, seeds for organic production were scarce and the farmers union had to import non-treated seeds from Togo, which proved to be a complicated bureaucratic venture. In addition, ginneries had to be cleaned before processing organic cotton owing to the risk of contamination. Ginning of organic cotton was thus scheduled only at the very end of the season, and O&FT cotton sales were delayed. All in all, GM cotton raised seed prices, complicated production, processing and certification and demotivated some farmers to continue with organic production.

An institutional crisis that had developed within the farmers union in Burkina Faso (UNPCB) for political reasons as well as the termination of a long-term and highly beneficial sales contract with the main buyer affected the farmers’ motivation and their adherence to the value chain.

In Mali, cotton sales and processing are concentrated within the parastatal Malian cotton company (CMDT). Therefore, the National Federation of Organic and Fairtrade Producers (FENABE, MoBioM until 2015) cannot engage and directly benefit from cotton sales. For two years, certified cotton was not sold at premium prices because CMDT had other marketing priorities. In this period, farmers suffered a combination of low yields and low sales prices. In addition, CMDT decided to gin organic cotton at the end of the season, which led to late sales of cotton and demotivated organic cotton farmers. Despite diverse efforts, the ginning schedule and cotton sales were out of the sphere of influence of the project and the producer organisation MoBioM.

In Kyrgyzstan, O&FT cotton sales are determined by the ability of the producer organisation BioFarmer to purchase cotton from farmers directly at the ginnery. Therefore, BioFarmer needed to access trade capital, which was not sufficiently and continuously available.

Economic impact

Besides having overcome debts, which is probably the main economic and social impact of the measures, all O&FT farmers together have benefitted from a total additional income of 11.2 million euros, or 107 euros per farmer and year, compared to conventional farmers. The calculation bases on the following parameters, which were defined and added up for each country and year. They account for the total certified cotton area of the three countries.

Yields: In Kyrgyzstan, O&FT cotton farmers invested in livestock, gaining access to farmyard manure they needed to maintain soil fertility and yields. Their average yields are comparable with conventional seed cotton yields (2 t to 2.5 t/hectare). In Burkina Faso and Mali, access to and application of organic manure or other fertilisers remained a challenge. In addition, conflicting interests prevented organic cotton from growing faster: the main business interest of CMDT and UNPCB is in the promotion of conventional cotton. Furthermore, GMO contamination in Burkina Faso led to a marginalisation of organic areas to less productive lands. As a result, yields of conventional cotton were 60 per cent higher (723 kg seed cotton/ha) than those of organic cotton (441 kg seed cotton/ha).

Sales prices: In Kyrgyzstan, the average price was 18 per cent higher for organic seed cotton (34.6 som/kg) than for conventional cotton (29.2 som/kg). In Mali and Burkina Faso, sales prices were around 60 per cent higher for organic cotton fibre (324 FCFA/t) compared to conventional cotton fibre (203 FCFA/t). These premium prices more than compensated the relatively lower yields. In addition, the farmer communities benefited from a total Fairtrade premium of 799,000 euros, or 5 euros (West Africa) and 28 euros (Kyrgyzstan) respectively per farmer and year.

Input costs are, on average, 73 euros/ha lower in organic farming compared to conventional farming, thanks to the abandonment of chemical pesticides, herbicides and synthetic fertilisers. Total savings in input costs amounted to 8.4 million euros from 2002–15, or 74 euros per farmer and year. Labour costs are not included in this calculation. Organic production usually requires more labour input during the vegetation period, whereas, because of the higher yields, in conventional cotton production, manual labour is higher during the harvest period.

Social and environmental impact

Despite the considerable economic benefits, social benefits were the primary reasons for farmers to adopt organic practices. These include better health thanks to the abandonment of harmful production inputs, as well as access to productive lands and cash crop production for women in West Africa. Other benefits were reduced production risks thanks to enhanced soil fertility and diversification, access to rural advisory services, and markets for rotation crops. The benefits from the production of rotation crops have been so compelling that numerous organic farmers have limited cotton production in favour of more beneficial organic food crops, such as vegetables or sesame. In addition, the renunciation of an estimated 6,000 t of chemical fertilisers led to a calculated reduction of around 11 million t of CO2 emissions in the period between 2002 and 2015.

Key learning

Producer organisations play a key role in value chains. Today, they have the capacities to offer rural advisory service for organic agriculture, ensure input supply, and manage internal control systems as well as organise external certification. BioFarmer in Kyrgyzstan reached a self-financing of 100 per cent based on sales margins, while the producer organisations in Mali and Burkina Faso cannot benefit directly from cotton sales because of the persisting sales oligopolies of the cotton companies. What key lessons can be derived from this cotton experience?

- Access to trade finances is critical for the profitability of the producer organisations. In Mali and Burkina Faso, trade capital is available via the national cotton unions, whereas in the privatised Kyrgyz cotton sector, access to trade capital continues to be a limiting factor. If the producer organisation lacks the capital to pay organic cotton in time, organic farmers relinquish premium prices and sell organic cotton at a conventional price. This reduces the margin the co-operative gets from sales and constrains the sustainable business. Promising approaches to access trade capital include pre-financing by the cotton trader, loans from local and international banks, as well as investments by local cotton seed processors. Donor organisations can also play a key role by offering bank guarantees.

- The policy environment can seriously affect the development of organic value chains. In Mali and Burkina Faso, the parastatal cotton companies have a mono-/oligopoly on cotton trade, input sales and ginning services. Ginning and sales of organic cotton thus fully depend on the priorities of these institutions, and the farmer organisations cannot claim for the full margin from cotton sales. Further, the cotton companies are heavily involved in agricultural inputs business, which limits their interest in strengthening the organic sector. In particular, in non-privatised settings, policies conducive to organic sector development have proved to be key to the sustainability of the O&FT cotton value chains.

- Investments in O&FT value chains should entail an advocacy component that addresses e.g. the introduction of organic curricula in education institutions and in public extension services, the protection against GMOs, as well as the business environment of producer organisations

- Farmers’ adherence to the value chain is key for the sustainability of the producer organisations’ business: In the first years, farmers need the most support in order to get acquainted with the O&FT system, whereas yields increase only after some years of organic farming. Furthermore, organic certification usually requires a conversion period. Hence, farmers who leave the value chain at an early stage drive the costs of the producer organisation by generating less margin. Five aspects support farmer adherence to the sustainable cotton value chain:

- Services to mitigate risk of GMO contamination.

- Beneficial fund flows to farmers via pre-financing of inputs, timely sales of cotton and rotation products. In this regard, trade capital, diversified production and marketing systems are key.

- Sales prices that compensate lower yields or trigger investments into organic intensification instead of organic by default.

- Diversified production and marketing systems to increase farm income, reduce cluster risks and enhance fund flows. Since the fibre market is different from the staple market, a separate business network must be established to market rotation crops of cotton.

- The Fairtrade premium as well as public funding are important to bridge the in-conversion phase of organic farmering.

Outlook

SECO and Helvetas support to the O&FT cotton value chains in Mali and Kyrgyzstan ended in 2016, while the Burkina Faso project runs until mid-2017. Owing to the growing market demand for O&FT cotton, the improved competences of the producer organisations, the alluring benefits for farmers, as well as the international community’s increasing interest in supporting organic agriculture, there is a high probability that the business of these three O&FT cotton value chains will be long-lasting and outlast the completion of SECO and Helvetas’ engagement.

Stefanie Kaegi

Advisor sustainable agriculture and rural advisory services

Andrea Bischof

Senior advisor sustainable agriculture and organic farming

HELVETAS Swiss Intercooperation

Zurich, Switzerland

Contact: Stefanie.Kaegi@helvetas.org

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment