Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Revitalise the Aid for Trade initiative

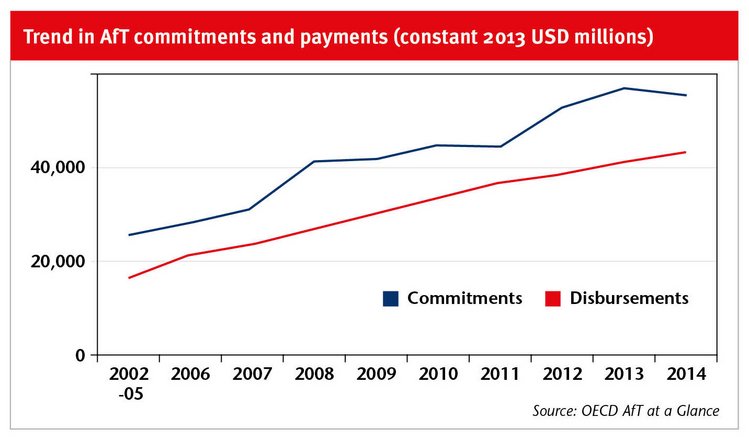

Aid for Trade (AfT) was conceived as a joint effort by the World Trade Organization (WTO) and donors to engage developing countries during the Doha Development Round (the current trade-negotiation round of the WTO which commenced in November 2001), in an attempt to increase their confidence in the availability of trade-related adjustment support stemming from further trade liberalisation. Since its inception, the AfT initiative has recorded a significant increase in financial commitments and disbursements totalling approximately 393 billion US dollars in commitments since 2006. It constitutes about a third of all Official Development Assistance (ODA) annually. However, the trend in commitments is levelling off (see Figure).

Eroding confidence in AfT?

The question is whether both developed and developing countries still have confidence in the Aid for Trade initiative. This may no longer be the case. Just as AfT was a response to the crisis in multilateral trade negotiations and donor expediencies ten years ago (see Box below), there is a need for its reassessment on the basis of shifts in the global trading environment, pressures on donor governments and needs of developing countries. The global trade slowdown since 2015 and growing scepticism over the value of trade need to be factored into an upgrade of the AfT initiative. The United Kingdom’s departure from the European Union – the so-called Brexit – is symptomatic of a broader popular disillusionment with globalisation and free trade. Spurred on by these sentiments, developing countries are also emboldened to criticise on-going liberalisation efforts, with for example Tanzania recently walking out of the Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA). At the same time, the AfT initiative is more important than ever to retain momentum towards opening up the global marketplace. At its most recent meeting, the G20 called for advancing and sharpening the AfT initiative. Many donors, such as the European Union, Germany and Australia, are also in the process of reassessing their trade and AfT efforts, not least the United Kingdom after the Brexit decision. However, the weaknesses of the Initiative are hard to conceal.

The Aid for Trade initiative

The AfT initiative was officially launched at the Hong Kong Ministerial Conference in December 2005 to recognise the role of trade in sustainable development and to mobilise resources for addressing trade-related constraints in developing countries. For donors, it was also an effective way to increase the scale and effectiveness of development aid through an alternative, traderelated mechanism. The Initiative was accompanied by a joint WTO–OECD monitoring effort, which recorded a consistent increase in annual AfT support since 2006 and collated evidence of the impact of AfT on reducing trade costs, increasing trade and ultimately contributing to sustainable development.

Vague definitions and unclear financing

One of the main weaknesses of AfT has been definitional. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the WTO, “projects and programmes should be considered as AfT, if these activities have been identified as trade-related development priorities in the recipient country’s national development strategies”. In practice, the exact definition is left to members of the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC), and different organisations apply different definitions for AfT.

AfT investments support recipient countries’ efforts in five different categories: 1) trade policy and regulations, 2) trade development, 3) trade-related infrastructure, 4) building productive capacity and 5) trade-related adjustments (direct contributions to a government budget to adapt to a changing trade environment, e.g. assistance to manage shortfalls in the balance of payments). Categories 1 and 2 constitute trade-related assistance (TRA), which is AfT in its narrower sense. Existing ODA flows are “labelled” as AfT based on these categories and are likewise coded in the OECD development co-operation statistical databases. At the same time, it is a struggle not to conflate funds labelled as AfT with resources for broader development.

Therefore, even senior academics question if these resources have been truly additional, as originally envisioned, with many donors struggling to meet their 0.7 per cent of GDP annual commitment to development aid. According to economist Joseph E. Stiglitz, “AfT has failed to live up to its promise of additional, predictable and effective finance to support developing countries’ integration into the global economy.”

There is also deep frustration among developing countries about AfT flows. Tanzania’s former President Benjamin Mkapa justified the country’s exit from the Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) on grounds of the meagre donor commitment made to date, while Tanzania is recorded as one of the largest and most consistent recipients of AfT resources. Partly, his reaction reflects the confusion over stricter and broader definitions of AfT.

Disputed impact of AfT on trade, growth and development

The history of the AfT initiative was rooted in the desire to improve development impacts through increased trade. At the same time, its parameters were not very precisely delineated, nor was it sufficiently resourced with monitoring and evaluation capacity to explore these linkages. According to Gamberoni and Newfarmer, “impact evaluation was conspicuous for its absence in the AfT debate”. Generally, there is limited and at times contested evidence of the link between AfT, trade, economic growth and sustainable development.

The global trade agenda is characterised by assumptions relating to the positive relationship between tariff reduction, trade flows, growth and development. However, with the demonstrated asymmetry of the Uruguay Round (the 8th round of multilateral trade negotiations within the framework of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), spanning from 1986 to 1994), against the interests of developing countries, increasingly, evidence of the linkage between trade liberalisation, growth in trade and welfare benefits is also more disputed and differentiated. Results vary significantly depending upon the category and sector of AfT support, as well as the location and income level of the recipient, with Least Developed Countries (LDCs) being particularly disadvantaged.On the one hand, evidence suggests that AfT support, especially trade facilitation, trade policy and infrastructure support, has a significant impact on reducing trade costs and increasing trade and welfare benefits globally. The costs of logistics and poor trade facilitation are much higher than tariff costs. According to the World Economic Forum, reducing these non-tariff barriers could increase world gross domestic product (GDP) over six times more than would be the case if all tariffs were removed.

Based on a literature review, Martuscelli and Winters conclude that greater trade liberalisation increases income and ultimately improves welfare. According to the OECD, one additional dollar invested in AfT generates around eight dollars of exports from all developing countries and up to 20 dollars from LDCs. Reviewing aggregate, global data, Helble et al. suggest that a one per cent increase in assistance to trade facilitation increases global trade by about USD 415 million. A one per cent increase in trade policy support could increase global trade by USD 818 million. Ivanic et al. conclude that efforts in three categories of AfT (as per the OECD categorisation of ODA) result in the world-wide reduction of trade costs by 0.2 per cent and generate a welfare gain of USD 18.5 billion. Vijil and Wagner argue that a ten per cent increase in infrastructure investments leads to an average increase of export to GDP ratio of 2.34 per cent for developing countries. Hallaert nevertheless warns that improving infrastructure will not have a significant impact on trade and, through trade, on economic growth, unless it is accompanied by services and regulatory reforms.

Cali and te Velde find the impact of trade policy reform on the cost of trading more mixed. Vijil and Wagner concur, suggesting that trade policy interventions have limited impact. The most sobering conclusions are by Busse et al., who conclude that actually, none of the types of AfT considered are effective in reducing the costs of trading specifically in LDCs.

At the same time, from the regional experience of TradeMark East Africa (an organisation funded by development organisations to grow prosperity in East Africa through trade; see also article "Boosting trade with better border infrastructure"), infrastructure and trade facilitation support have resulted in significant time and cost savings to traders and ultimately increased both intra-regional and global exports. According to the OECD/WTO, the sheer quantity of activities described in the case stories submitted to the review process demonstrate the turning of trade opportunities into trade flow and helping men and women make a more decent living. However, Hallaert calls to attention that none of the case studies explore failures and their value for learning may therefore be compromised.

Incremental progress through regional trade, e-commerce and broader stakeholder engagement

Just like when the AfT initiative emerged ten years ago, there is a need to review and revisit it based on new global opportunities and challenges. With the slowing pace of global trade and the growing wave of public scepticism over globalisation and free trade agreements in particular, the importance of AfT for addressing the trade adjustment costs and challenges of developing countries is even more important. With the failure of the Doha Development Round, dynamic regional initiatives provide a useful framework for making incremental progress. Supporting regional AfT efforts can be particularly fruitful in targeting regional trade flows and LDCs. Lammersen suggests that regional organisations can be honest brokers in helping developing countries find common ground, offering financial incentives, building human and institutional capacities, and harmonising regulations. This has been already reflected in the growing financial commitment among donors to support regional initiatives as per OECD data.

There is also clear willingness among WTO members to deepen co-operation in specific areas, such as trade in services, e-commerce, even fisheries, as made evident at the recent WTO Public Forum discussions. Great opportunities present themselves in deeper engagement with the private sector and non-DAC donors, also for the identification of alternative, sustainable sources of AfT finance. At the same time, alternative financing should not be confused with aid allocations, just as the new emphasis on promoting donors’ trade interests should not be confused with AfT. Even the Brexit decision could be harnessed to champion the case of trade and development, as suggested by the Overseas Development Institute.

With the signature of the Paris Climate Agreement, there is both the imperative to mainstream climate issues into the AfT agenda and an opportunity for climate finance to learn from the AfT experience; especially relating to the crucial principle of additionality and lessons from mainstreaming AfT into ODA flows. Sustainable Development Goal 8, on Decent Work and Economic Growth, as well as the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement provide the requisite global political context and impetus for the continued role of AfT in the promotion of inclusive and sustainable economic growth. The new global trade environment therefore creates both opportunities and challenges for the AfT agenda, but most clearly, it demonstrates a need for its revitalisation.

Johanna Polvi

Independent Consultant

Berlin, Germany

johanna.polvi@yahoo.co.uk

References and further reading

- Busse, M., R. Hoekstra and J. Königer (2012). “The Impact of Aid for Trade Facilitation on the Costs of Trading”. Kyklos. 65: 143–163.

- Cali, M. and D.W. Te Velde, (2011). “Does Aid for Trade Really Improve Trade Performance?” World Development. Elsevier, Vol. 39(5): 725-740.

- Gamberoni, E. and R. Newfarmer (2014). “Aid for Trade: Do Those Countries that Need it, Get it?” World Economy, Special Issue: Aid for Trade. Edited by Melo, J. Vol. 37 (4): 542–554.

- Hallaert, J.J. (2012). “Aid For Trade Is Reaching Its Limits, So What's Next?” GEM Working Paper.

- Helble, M.C., C.L. Mann, and J.S. Wilson (2012). “Aid-for-trade facilitation," Review of World Economics. Springer, Vol. 148(2): 357-376.

- Ivanic, M. C.L. Mann and J.S. Wilson (2006). “Aid for Trade Facilitation”. Global Welfare Gains and Developing Countries.

- Lammersen, F. and M. Roberts (2015). “Aid for Trade 10 years on: Keeping it Effective”, OECD Development Policy Papers, No. 1, OECD Publishing, Paris.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jrqc6q4xxr5-en - Martuscelli, A and L. Winters (2014). “Trade Liberalisation and Poverty: What have we learned in a decade?” London, CEPRI. http://www.cepr.org/active/publications/discussion_papers/dp.php?dpno=9947

- Mendez-Parra, M., D. Willem te Velde and L. Alan Winters (2016). ODI. https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/resource-documents/10852.pdf

- OECD (2013). Aid for Trade and Development Results: A Management Framework, The Development Dimension. OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264112537-en

- OECD Aid for Trade at a Glance. Interactive Database. https://public.tableau.com/views/Aid_for_trade/Aid_for_trade?:embed=y&:showTabs=y&:display_count=no&:showVizHome=no#1

- Razzaque M., te Velde, D. (eds.) (2013). Assessing Aid for Trade: Effectiveness, Current Issues and Future Directions.

- Stiglitz, Joseph (2013). The Right to Trade: Rethinking the Aid for Trade Agenda.

- Vijil, M. and L. Wagner (2010). “Does AfT Enhance Export Performance? Investigating on the Infrastructural Channel”. Working Paper 10:07. SMART-LERECO, Rennes.

- WEF (2013). Enabling Trade: Valuing Growth Opportunities, Geneva, available at www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_SCT_EnablingTrade_Report_2013.pdf

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment