Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Why property rights matter

The fundamental reason why property rights are at the centre of the economic growth nexus is their pervasive and important role in shaping incentives in political, social and economic exchange. For instance, it is often asserted that, when land property rights are secure people have more incentives to invest into land improvements because their efforts are adequately protected. Next, secure land titles facilitate borrowing on capital markets since the land can then be used as a collateral. Finally, clear land ownership rights allow for transfer of those rights through sale or lease. This improves the efficiency in resource allocation as it enables the land to be worked by those who are best fit to do so.

Secure land property rights are also of crucial importance in the context of poverty alleviation. In many developing countries, land remains the only source of livelihood for poor and marginal households. Improved security of land rights, thus, translates into more secure access to housing, food and income. Furthermore, when basic needs like shelter and nutrition are met, the poor are more likely to be able to afford education, which would help them exit the vicious cycle of poverty.

Property rights and law

A high-quality legal system is, on the other hand, an absolute conditio sine qua non for establishing a system of secure land property rights. Law defines the bundle of rights in land which may range from full private ownership, use rights and lease rights to customary rights. It also defines restrictions and limitations imposed by the state on those rights, as well as conditions under which land can be expropriated from a landowner. Law sets out the rules for land transfers, whether through sale or lease, and stipulates how land is inherited. Law also provides a foundation for creating institutions responsible for land administration as well as defining mechanisms for land dispute resolution. Despite their importance, property rights associated with land are either non-existent or ill-defined across a number of countries in the world. In many developing countries, land rights continue to be governed through a complex framework of often conflicting formal and informal rules resulting in a situation of legal pluralism. This ambiguity with property rights over land greatly distorts incentives and has an adverse impact on economic performance.

Legal systems based on property rights and land tenure

In our research, we collect comprehensive data on property-related legislation and patterns of land tenure for 146 countries across the world, spanning the entire 20th century. Then, we use econometric techniques to group similar countries together and derive a new classification of legal systems based on property rights and patterns of land tenure. There are seven distinct legal systems operating around the world: fully private ownership systems, state-dominated systems, private-state mixed systems, private ownership systems with customary elements, de jure customary systems, de facto customary systems, and religious systems.

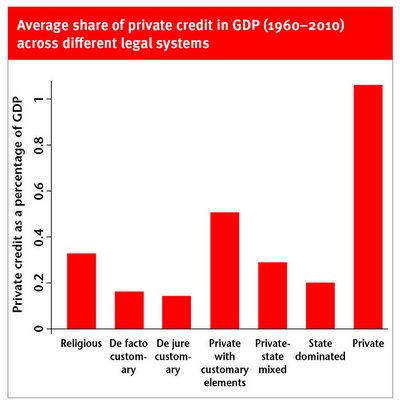

Private ownership systems include countries such as Australia, France and Germany, where the source of law is solely formal, written statutory law and where the law-making process includes strict checks and balances. Private land ownership constitutes an important part of total land ownership and is unambiguously protected by Constitution. Cadastres are well-developed, and the correctness of land registers, where all land rights are systematically recorded, is typically guaranteed by the state. This has facilitated the practice of using property as a collateral when obtaining loans from the banks.

In contrast, state dominated systems (i.e. China, Belarus, Uzbekistan) either do not recognise private ownership or have only very recently allowed for this form of ownership in their legislation. Individuals, households and organisations typically access land through allocated land-use rights or land leasing from the state, offering little to no protection and easy for the state to cancel. The state has also a very decisive role in land use, planning and development. For example, after introducing a series of law changes promoting private property, the government of Tajikistan continued to mandate production of cotton even for privately owned farms. Cadastre and land administration in general are underdeveloped, lack resources and technical support making it nearly impossible to use property for accessing loans.

Private-state mixed systems can be thought of as countries with a socialist legacy that underwent transition in the 1990s to a system fully supporting private property rights. Despite the fact that post-socialist land reform programmes – more or less successfully – privatised land, the state continues to own a significant share in total land ownership, especially with respect to agricultural land. Unlike countries belonging to state-dominated systems, many of the countries in this system (such as Croatia, the Czech Republic or Hungary) had well-functioning cadastres and land registers before the socialist period, and their activities simply resumed after transition.

One characteristic common to the following three legal systems is the existence of customary laws and modes of tenure to a greater or lesser extent. Countries belonging to the private ownership system with customary elements were steadily replacing indigenous tenure throughout the past century in favour of private ownership. While customs remain to partially govern matters of, i.e. inheritance, indigenous land tenure has been declining through decades. Formal law has, in general, unfavourably treated indigenous claims to land, and only very recently have some of these countries, such as Bolivia, Ecuador and Peru, started to recognise customary rights in their statutory legislation. Despite a relatively long history of private ownership, the majority of the countries have also failed to adequately protect private property rights, which is further complicated by persistently unequal land distribution.

The most distinct feature of de jure customary systems, on the other hand, is the formal recognition of customary tenure in their formal laws and Constitutions. Although private land ownership is not prohibited, community ownership prevails as the most dominant ownership form. One country representing this legal system is Botswana, where administrative power over residential, arable and grazing land allocations formerly held by chiefs is transferred to twelve district Land Boards. Allocated land is free of charge and inheritable, but cannot be sold. Also, the Land Boards have the authority to cancel customary rights to such land when it is not being used in accordance with the purpose of allocation.

In contrast to de jure customary systems, de facto customary systems do not officially recognise community-based tenure although such tenure type continues to be dominant. Some countries, like Angola, Nigeria and the Central African Republic, provide little or no reference to community land tenure, while Burkina Faso and Senegal have legally abolished it altogether. Also, there are countries (i.e. Burundi, Niger) that recognise customary rights to land but only in context of their conversion into private individual rights. Aside from non-recognition of customary tenure, these countries share a lot of similarities with de jure customary systems. For example, both systems suffer from underdeveloped or non-existent democratic institutions as well as contradictions between newly enacted and old colonial legislation that is in some cases still in effect.

Finally, religious systems, as their name implies, derive rules for governing land from religion. These rules are always codified and constitute part of a country’s statutory legal framework. Religious systems also tend to be more inclined towards redistributive land reforms. Most importantly, religious rules are strictly followed in matters of property inheritance that typically exhibits gender differentiation. State ownership of land is the most prevalent form (i.e. in Afghanistan, the United Arab Emirates or Malaysia), although some religious systems have a longer history of private land ownership (like Iran and Lebanon).

The impact of legal systems on education

Human capital accumulation is, according to economic theories, commonly emphasised as one of the main growth determinants. To measure human capital, we use school enrolment rates from the World Bank (2012) and Barro and Lee’s (2013) educational attainment data. The results of our research suggest that different legal systems of property rights and land tenure have strong impacts on educational outcomes. We also find empirical evidence that some of these effects are gender-differentiated, suggesting that land might be an important source of gender disparity.

Looking at the enrolment for different educational levels (World Bank), all legal systems are significantly lagging behind fully private ownership systems. De jure customary systems, where dominant community tenure is officially recognised by law, typically see the least secondary school enrolment, followed by religious systems. This holds true even after we have checked how poor countries belonging to these systems are. On the other hand, while private-state mixed and state- dominated systems also exhibit lower rates of secondary school enrolment, the effect is less significant, and its magnitude is not so large. This is easily explained by the socialist legacy characteristic of both systems that supported programmes promoting universal education.

When tertiary-level education is taken into account, however, state-dominated systems fare worst out of all systems, closely followed by private ownership systems with customary elements, religious and de jure customary systems. In the case of countries belonging to private ownership systems with customary elements (most of Latin America), such strong negative results might be driven by high land inequality, where only the wealthy landowning elites could afford higher education throughout the past century. The results also reveal that religious, de jure and private ownership systems with customary elements tend to have significantly larger shares of female population that have not moved past primary schooling. Women in these systems often access land only through their male relatives, such as the father, husband or brother. Furthermore, inheritance rules in these systems either prevent women from inheriting land or allow them to inherit smaller shares than their male counterparts.

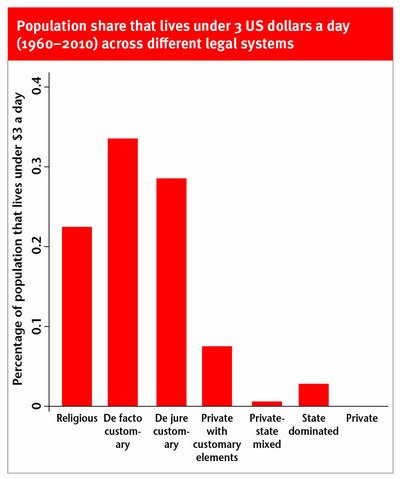

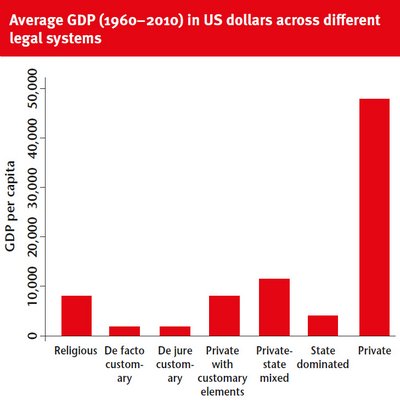

Overall, our results suggest that law plays an important role in establishing a system of secure property rights. We find strong support for the supremacy of private ownership systems compared to religious, customary, state and various mixed legal systems, not only in terms of education presented in this article, but also regarding a number of other indicators like investment and poverty. Our findings strongly support the initiatives for strengthening land property rights with the aim of reducing poverty, improving gender equality and increasing income per capita.

Ana Marija Dabo

Deakin University

Melbourne, Australia

adabo@deakin.edu.au

References & reladed literature

Barro, R., & Lee, J. W. (2013). A New Data Set of Educational Attainment in the World, 1950-2010. Journal of Development Economics 104, 184-198.

Besley, T., & Ghatak, M. (2010). Property Rights and Economic Development. Handbook of Development Economics, 5, 4525-4595.

De Soto, H. (1989). The other path. New York, NY: Basic Books.

De Soto, H. (2000). The mystery of capital: Why capitalism triumphs in the west and fails everywhere else. New York, NY: Basic Books.

FAO. (2002). Land Tenure and Rural Development. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

North, D. C. (2005). Understanding the process of economic change. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

The World Bank. (2012). World development indicators. Retrieved from: http://data.worldbank.org/

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment