Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Migration dynamics in sub-Saharan Africa – myths, facts and challenges

At first glance, statistics on global demographic trends seem to support the general notion of rapidly growing urban areas and deserted rural areas. According to the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA), 2008 was the first year in the history of humankind when more people were living in urban areas than in rural areas. The share of people living in cities and towns increased globally by about 125 per cent from 1960 to 2014. Today, more than 360 million people in sub-Saharan Africa live in urban areas. This number is expected to reach one billion by 2050. Globally, the share of urban population had already totalled about 3.5 billion by 2015.

Urbanisation myths – a reality check

In particular in the African context, rapid urbanisation has ever met the scepticism of policy-makers as increased crime rates, urban sprawl, fast growth of slum areas or even riots were – and still are – expected as potential consequences. Many countries have consequently put policies in place aiming to prevent rural-urban migration. At the same time, international development organisations have increasingly withdrawn support for urban development initiatives in favour of rural development projects, often justified by the argument that improving living standards in rural areas will help to mitigate the growth of urban poverty. The notion that more rural development may curb rural-urban migration is still quite efficacious. But this so-called sedentary bias is contradicted by empirical findings: In fact, at least initially, development and development projects that lead to higher incomes and increased living standards rather tend to stimulate migration than to mitigate migration processes. Areas characterised by high rates of extreme poverty in turn hardly produce migrants as very poor people simply lack the financial and other resources that are required to migrate at all. Or they just cannot bear the risks associated with migration, such as uncertainties concerning finding accommodation or employment at the place of destination. Only a certain level of social and economic development enables more people to increase their aspirations and to migrate.

Rural-urban migration: overestimated

But the fact that rural development projects are not a very effective measure to stop migration out of rural areas is not the only fallacy in this context. The other one is that rural outmigration is predominantly linked to urban in-migration and urbanisation, respectively. The contribution that migration actually makes to urbanisation in sub-Saharan Africa but also in other parts of the world is overestimated. Meanwhile, natural population growth in towns and cities is a stronger driver of urban growth than in-migration. Thanks to better health services and improved levels of food security, birth rates in African urban areas by far exceed death rates. Furthermore, the urbanisation rate in sub-Saharan Africa is still much lower as compared to East Asia, for instance. In other words, the share of the population living in rural areas in sub-Saharan Africa is not dramatically changing in favour of the urban share of the population.

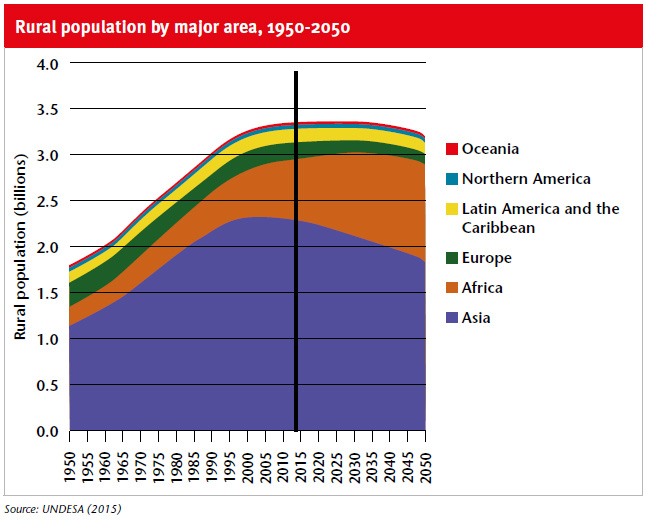

Population estimates by UNDESA assume that the African urbanisation rate will stagnate at about one per cent in the next three decades. Moreover, by 2050, slightly more than 50 per cent of the overall population in sub-Saharan Africa are projected to live in urban areas. By comparison, it is assumed that the urban population share in Europe will have reached the 80 per cent threshold by then. Thus, it would be an illusion to presume that the rural population in sub-Saharan Africa will simply “fade out” via a huge rural exodus within the next few decades. In absolute numbers, as compared to all other world areas, the rural population in Africa is in fact even set to increase over the next decades (see Figure below).

Internal migration: important, but largely ignored

Nonetheless, many African countries are characterised by a high degree of demographic mobility and migration rates. A lot of these migration movements within African countries are still rural-rural and are often temporarily limited or circular. The few studies dealing with internal migration in sub-Saharan Africa show that rural-rural migration flows are often even greater than rural-urban migration. A growing disinterest of young people in agriculture is often mentioned as a major reason for this high degree of mobility. Young people in rural areas of sub-Saharan Africa – about 70 per cent of overall African youth currently live in rural areas – are indeed affected by an increasing access to education, media consumption and communication technologies. That certainly changes their perceptions of rural life. But it would be another fallacy to perceive the young rural population in sub-Saharan Africa as actors without agency that are just being “pushed” or “pulled” away from rural areas. These young population strata are not a homogenous group but very diverse in terms of their educational, vocational and life perspectives.

Smallholder agriculture and subsistence farming is increasingly being rejected by young people in Africa due to tedious work conditions, lacking or insufficient market access, limited land or capital access or increasingly unfavourable ecological conditions through climate change and local environmental degradation. But that is not necessarily valid for agriculture in general, as what matters to many young people is opportunities for income generation – rather than the economic sector they are working in per se.

Without a doubt, agriculture plays a fundamental role in the rural economies of sub-Saharan Africa. The provision of employment opportunities in the agricultural sector is a key to economic growth and achieving food security. This is reflected not only in the Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP) process, for instance, but also in the reinvigorated donor activities in agriculture and rural development – in particular after the world food price crisis of 2007/2008. Debate on rural development and transformation within the last years has focused very much on issues like market integration of smallholder farms into value chains, better access to social safety nets and financial services or the creation of non-farm employment for farmers whose potential for market integration is very low. Internal migration as a potential in this regard has attracted astonishingly little attention, which is related not only to the already mentioned sedentary bias but also to the fact that there is hardly any data on rural-rural or rural-urban migration in sub-Saharan Africa. In particular, the links between large-scale land investments and migration are as yet dramatically under-investigated. The migration dynamics being discussed in the context of large-scale land investments are still almost exclusively related to farmers being expelled from their farms on account of these investments. The number of jobs that are created by a farm scheme run by agricultural investors depends mainly on which crops are actually grown and the (related) degree of mechanisation. Likewise, the income levels that can be earned by farm labourers in these schemes are often low, and the working conditions might be poor. Nonetheless, it can be assumed that land investments coming along with employment opportunities for contract farmers or farm labourers are an important driver of (rural-rural) migration dynamics in several African countries that have attracted a lot of agricultural investments (e.g. Malawi, Ethiopia or Tanzania).

What should be done?

Academic research and development policy have been dealing with the positive linkages between migration and development for quite some time now. Unfortunately, both research and policies addressing the interactions between migration and development focus mainly on international migration. As migrants usually do not migrate for individual reasons only but also try to support their families in their home areas, the mechanisms that constitute the positive potential of migration for development do likewise exist in internal migration dynamics. Interestingly, these mechanisms – financial remittances, which can be used for investments or educational or health related expenditures, knowledge transfers and technology transfers – also happen to be the positive aspects associated with large-scale land investments.

Especially in the African context, knowledge and data on internal migration dynamics – and in particular rural-rural migration processes – are largely missing. There is an urgent need to close these knowledge gaps and to generate more data and a deeper understanding of rural-urban and rural-rural migration processes in sub-Saharan Africa. Likewise, policy-makers would do well to reconsider their largely negative perceptions of internal migration processes as these do not automatically lead to rapid urbanisation processes with their negative circumstances on the one hand and “dying” rural areas on the other. It would make a lot of sense to come to a generally more hard-headed analysis and policies addressing internal migration in order to try to maximise the potential benefits and to minimise negative aspects. Fostering the positive potential could for instance mean to improve the infrastructure for remittances in rural areas or to create portals to provide migrants with better information about job opportunities. Minimising negative aspects could mean addressing the often miserable living and working conditions of migrant labourers.

Benjamin Schraven

German Development Institute (DIE)

Bonn, Germany

Benjamin.Schraven@die-gdi.de

References and further reading

- Anyidoho, N.A., J. Leavy and K. Asenso‐Okyere (2012): Perceptions and aspirations: A case study of young people in Ghana's cocoa sector. IDS Bulletin 43(6): 20–32.

- Beegle, K., J. de Weerdt, S. Dercon (2011): Migration and economic mobility in Tanzania: evidence from a tracking survey. The Review of Economics and Statistics 93 (3): 1010–1033.

- De Haas, H. (2006): International migration, remittances and development: Myths and facts. Third World Quarterly 26(8): 1269–1284.

- Fox, S. (2011): Understanding the Origins and Pace of Africa’s Urban Transition. Crisis States Working Paper No. 89, Crisis States Research Centre, London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Sumberg, J., N.A. Anyidoho, J. Leavy, D. te Lintelo and K. Wellard (2012): The young people and agriculture ‘problem’ in Africa. IDS Bulletin 43(6): 2–6.

- UNDESA (2015): World urbanisation prospects: The 2014 revision. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, New York.

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment