Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

The Ebola crisis and its effects on rural Sierra Leone

Epidemiologists locate the origins of the outbreak of Ebola in West Africa in the transmission from bats to human beings in the rural settlements along the Guinean Rainforest, a high biodiversity belt in the Mano River Union between Sierra Leone, Guinea, Liberia and Côte d’Ivoire. A rural population increase of two per cent annually and increasing economic exploitation of natural resources such as iron ore, diamonds, gold and land has sent settlements encroaching into formerly untouched natural reserves and animal habitats. Local authorities, often influenced by international investors and the dream of a prosperous future, rarely integrate environmental protection and management in their development planning, and the increasing human-animal interaction in fragmented landscapes with high deforestation rates could lead to the discovery of new zoonotic viruses. In the case of Ebola, fruit bats thrive in such changing environments along forest edges and have large communal roosts in wooded savannahs, tree hollows and, more recently, in buildings under roofs or overhangs.

The Ebola epidemic in West Africa was unprecedented and infected 13,982 people in Sierra Leone, claiming the lives of 3,955 victims. The index-case for Sierra Leone was a traditional healer from the rural chiefdom Kissy of the eastern district Kailahun who participated in a funeral event in Guinea in May 2014. This case alone infected above 30 family members, friends, and health staff who visited or cared about a “normal” woman of their society. The number of cases rapidly increased, and just eight weeks later, the country recorded above 500 cases. Most victims were poor, uneducated population groups in the urban slums and in rural areas. The spread of the disease was facilitated by poor living conditions with lack of sanitation facilities, poor hygiene and hand-washing practices, and by traditional burial rites in which the dead body is honoured with ceremonies where extended families and friends dance around and kiss the dead body. The symptoms of Ebola resemble common local diseases such as malaria and typhoid fever, and initially, the population distrusted the information shared by health workers and NGOs about the nature and consequences of this new killer virus. This remained a serious challenge for curbing new transmissions as people did not report on suspected cases and continued to care for loved ones at home.

The poor country’s health system was already weak and totally unprepared for responding to a health crisis of this magnitude. Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) in Kailahun District and the Red Cross Federation in Kenema District were the first to open Ebola Treatment Units and improve the laboratory testing. The district hospital in Kenema was the first government facility to offer treatment for people infected with the virus. However, in early July no specialist protection equipment was available, the professional knowledge to tackle Ebola was still very limited, and hygiene standards were low. So the hospital itself became a vector of Ebola, which spread to the urban population of Kenema and from there further on to the rest of the country.

The virus was able to move and spread geographically with human beings’ commotion and trade due to its long incubation period of 21 days during which an infected person who was not yet symptomatic could travel to other areas and spread the virus. The hesitation in the population to believe Ebola was real caused some infected victims to hide in their homes or even flee treatment centres, thus infecting family members and local caregivers.

“State of (Health) Emergency”

The Government declared a “State of (Health) Emergency” on the 31st of July 2014, hoping to gain control over the spread of the virus. Measures included the prohibition of traditional funeral ceremonies and the conduction of initiation rites by secret societies, closure of local markets and other public meeting points, closure of schools, bans on workshops, business meetings and group gatherings of any kinds, and formulation of local bye-laws to regulate the social interaction of community members and avoid cross-travelling of strangers. Road control measures to restrict travel and trade came into effect with police and military force and checkpoints set up along all major roads, curfews were put in place to restrict travelling times, and both vehicles and passengers required permits to travel within the country.

The proclamation of a state of emergency created further insecurity around the national socio-economic framework conditions, with many foreign investors leaving the country. Fear, uncertainty and frustration started to spread between the villages and urban settlements.

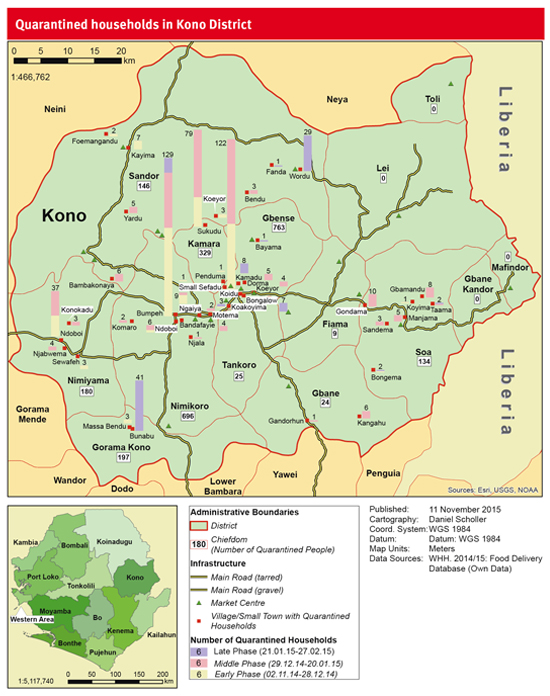

The virus spread unevenly and hit some villages directly and hard with many infected community members – sometimes even entire families were nearly annihilated. In those cases, additional restrictions including village and household quarantining – ‘house arrests’ – were enforced (see figure below). Quarantine of a village or household lasted a minimum of three weeks, but in many cases, it took about ten weeks until a community was free of Ebola. The number of villages quarantined and directly affected varied from district to district from 14 up to 50 communities. In Southeast Sierra Leone, the Ebola outbreak was defeated within a timeframe of 15 to 25 weeks per district.

The impact on rural livelihoods

Just as the virus spread unevenly across the country, the state of emergency also had diverse effects on the country and people’s livelihoods. It is necessary to make distinctions between the national economy and rural income sources, between urban and rural areas, and between those areas affected directly by the virus with a high infection rate and those mainly affected by the mitigating measures.

The economy: The Ebola crisis caused an estimated 13 per cent loss in GDP for 2015. Entrepreneurs paused operations, investment decisions were postponed, and many foreign investors, aid workers and elite Sierra Leoneans left the country. Sierra Leone’s exceptional economic growth rates in recent years has been largely driven by export of minerals, a sector dominated by foreign companies, and the investor flight caused a severe drop in GDP. However, the mineral sector is highly mechanised and generates only limited jobs, and sector revenues are not always experienced as direct benefits for the rural population. But the local agriculture markets and farming activities were disrupted, and widespread market insecurity was affecting the main trading centres in the country. Some traders went out of business, while others gained new market advantages. For example, market insecurity affected the cocoa sector – an important source of both export revenues and income for farmers – in both negative and positive ways. During the cocoa harvesting time from September to November 2014, the number of active foreign traders had dropped significantly, and local traders bridged the gap. This allowed farmers to focus on the quality of the product as demand was ‘slower’. Production decreased slightly but was compensated by higher prices for better quality.

The Ebola response, with its immense international support and funds, also created new jobs. New product supplies, especially hygiene products, were introduced by the local traders, and a campaign of basic health education stabilised many local safety nets.

Agricultural production: The Ebola virus disease (EVD) and the mitigating impacts resulted in less agricultural outputs than expected in many parts of the country. The planting season in the spring of 2014 occurred late because of late rains and coincided with the beginning of the outbreak in the Southeast. Local bye-laws imposed restrictions on movement and bans on group labour, agricultural inputs were not accessible due to trade restrictions, and people were afraid to work under the rain and contract any illness that would confuse them with Ebola patients. Villages with EVD victims were put under quarantine with no opportunity to access their farms to weed, scare animals away or harvest their fields – nationwide three-day lockdowns in August and September had similar negative impacts on agricultural work.

Rural families predominantly active in subsistence farming of the directly affected communities experienced poorer harvests of key crops such as rice, cassava, beans and groundnuts. Many households were forced to consume some of their seeds instead of stocking them for the new planting season. It appears that many households have cultivated both a lesser quantity and range of crops during the rains in 2015, and key crops may be in short supply even after the next harvests to come.

Household income: The majority of the rural population depend on sale of agricultural products and on petty trading of goods such as condiments, slippers, soap, etc. – many have limited access to bigger markets and limited opportunities for off-farm income sources, and cash income is very low. Poor harvests and restrictions on market activity caused rural families to lose small but important income sources normally used to invest in their farming and for expenditures on health, education, etc. However, people with higher dependency on markets and people in urban and peri-urban areas who are making a living entirely from trading or in the service sector (catering, entertainment, etc.) experienced serious constraints on their livelihoods.

The ‘village economy’ proved to be fairly resilient and adaptable, and rural people were able to compensate for the drop in regular income sources. Especially women engaged more in casual labour in the village such as groundnut harvesting and palm oil processing, but it appears that the traditional system of mutual labour exchange became ‘monetarised’ – where women would normally offer assistance to each other for the provision of a meal during the work, they were now paid in food to take home.

With the lifting of travel bans, the rural economy began to pick up again, and the rural population now report improved earning power, although some still rely on loans or remittances. However, many consumed their seeds and savings, and while this allowed them to feed their households during the outbreak, large numbers of households are now left with exhausted social safety nets and reduced investment capacity.

Consumption of bush meat and collection of wild foods and medicines: Bush meat is an important source of animal protein in rural Sierra Leone, but was officially condemned during the outbreak given the risk of animal-human transmission of Ebola. Many households stopped or reduced the consumption of bush meat, but it was still traded although under nicknames and on a lower scale. Rural households commonly rely on wild foods such as roots and tubers but also on wild fruits and green during periods of food scarcity, and they regularly collect wild medicines such as plants, herbs and barks for the treatment of common illnesses such as malaria, worms, dysentery and skin diseases. But the Ebola sensitisation clouded the collection of ‘coping foods’ from the forest and medicinal plants with ambiguity – some people were afraid to enter the forest for fear of contact with wild animals, and in some areas, the local authorities imposed local bye-laws and restrictions on who could enter the forest and for what purpose. The use of wild medicines appeared to continue to some extent during the Ebola outbreak, while the formal health system was overburdened with the Ebola response and the rural population – who already have only limited access to healthcare – were afraid to get near the health facilities.

Hygiene practices: Some hygiene practices may have actually improved thanks to the fear of Ebola. Many households have put additional measures in place such as more regular changing of stored drinking water, boiling or purifying drinking water, washing kitchen utensils with soap and less sharing of them with other people and households. Hand-washing with soap or ashes has likely also improved with hand-washing facilities put in place in front of communal facilities and even private households all over the country. Some rural communities also constructed fences around their water sources and guarded the water wells and boring holes in response to the widespread rumour that water sources were poisoned to deliberately increase the number of Ebola cases and thus attract more ‘Ebola response money’ for the government from the international donors.

Health systems: The Ebola outbreak had wider negative impacts on public health. The health system was overburdened, people were afraid of going near health facilities, and thus many other diseases also went untreated, child mortality increased, not least as people were afraid to enter the health facilities. Immunisation programmes for children for polio, measles, etc. were halted during the outbreak, but reactivated with mass vaccination campaigns in April 2015. During the Ebola Response, the hygiene standards of rural health care centres – known as peripheral health units – have been considerably increased. Many practitioners from hygienists through nurses to burial teams have been technically trained and now constitute an enhanced human resource for rural healthcare. In the post-Ebola transition phase, significant donor and government resources will be dedicated to upscaling service delivery and establishing an integrated disease management programme.

Social stigmatisation: The virus can be found in the male semen for more than six months after an Ebola survivor has been released from medical treatment. Survivors remain a potential reservoir for a resurge of the disease, and cases of infected female partners have already contributed to a stigmatisation of Ebola survivors by their host communities. During the outbreak, survivors who returned to their villages were sometimes confronted with stigmatisation. But gradually, as the Ebola response made donor programmes and funds available to victims of the disease, being a former Ebola patient became more accepted and sometimes so ‘lucrative’ that even fake survivors started to present themselves. Survivors may need hard-to-get specialist services as they suffer health issues like eye problems (uveitis), joint pain, headaches and psycho-traumatic experiences. But awareness-raising and livelihood campaigns that support the reintegration of survivors now also concentrate on the relatives of victims, especially ‘Ebola orphans’ – children who lost their parents during the outbreak – in acknowledgement of the fact that both those directly affected by the virus and communities broadly have borne the burden of the Ebola crisis on their livelihoods and on their minds.

Summing up …

The state of emergency still lingers over the country, but restrictions have gradually been lifted throughout 2015. Schools reopened in May, and in August, people could gather in public, dance in the nightclubs and hail a motorbike taxi at night-time again. One year after the crisis, the local economy is gradually getting back on its feet, and people are patiently rebuilding their livelihoods.

The severity of the Ebola crisis was experienced across the country, and the array of consequences and impacts on Sierra Leone’s social and economic fabric is not yet fully understood. Villages affected with a high number of cases suffered the direct experience of deaths, quarantines, food shortages and social trauma, whereas communities without EVD cases strained with the effects on restrictions on movement, trade and agriculture. Despite the effects on the national economy, the government managed to balance the market insecurity and restrictions well and to avoid civil unrest in rural areas by facilitating the transport of essential goods such as food. The rural subsistence-based population proved its remarkable resilience and ability to cope throughout a crisis posing a number of constraints on their livelihoods and causing widespread public uncertainty and apathy. An already poor population has now been left even more vulnerable, but is slowly regaining optimism for the future.

Jochen Moninger

Country Director Sierra Leone

Jochen.Moninger@welthungerhilfe.de

Mathilde Gronborg-Helms

Expert for Nutrition

Deutsche Welthungerhilfe

Kenema, Sierra Leone

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment