Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Small fish with a big potential for women’s business?

The small fresh water sardine-like silver cyprinid (Rastrineobola argentea) is traditionally one of the most important fishery species for the food security of the local population around Lake Victoria. Next to the imported Nile Perch (Lates niloticus), it has become the second most important commercial species. With a surface of 68,000 km2, Lake Victoria is the largest lake in Africa. It is bordered by three countries: Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda. Even though Kenya only governs six per cent of the lake’s surface, local catches of the silver cyprinid, known locally as omena (dagaa in Tanzania, mukene in Uganda) accounted for more than half of Lake Victoria’s total fish landings (456,721 metric tons) in 2011.

The development of the sector

Supported by international investment, the export-oriented Nile perch fishery has constituted the highest landings in volume and become a major source of foreign revenue. This development has significantly changed the traditional multi-species into target species oriented fisheries. Thanks to its lower value, omena has maintained its role as the most dominant fishery resource sold to end consumers in local fish markets. The maximum sustainable yield (MSY) for the Kenyan omena sector of Lake Victoria was estimated at 190,000 tons in 2000. In 2008, the production of omena of 47,000 tons, valued 17 million euros, was still far below the estimated fishing potential. In Kenya alone, about 850,000 people directly depend on this fishery. Four main market channels developed that support over two million people. These include both local and export human food channels. While human food channels represent 30 per cent of total annual production, at 70 per cent, local and export-oriented animal feed channels account for the lion’s share (Kamau & Ngigi, 2013). Export includes fishmeal for pet food and, to a minor extent, salted high-quality omena for the Eastern and Southern African markets. A significant but unrecorded quantity of omena milled in Kenya comes from Tanzania and Uganda, either legally or illegally (in order to avoid customs duties and import tariffs).

An important element of food security

Estimated per capita fish consumption in Kenya ranges from 3 to 5 kg per person and year. Omena accounts for 35 per cent of the country’s total fish consumption. By comparison, Nile perch is more expensive and is not the preferred fish by Kenyan taste. With tilapia prices having tripled over the past six years, omena has gained popularity, resulting in a demand for better quality omena at better prices. Since 2012, it has also been sold packaged in supermarkets.

Omena has the advantage of divisibility and affordability. It is valued thanks to its low cost, nutritive value and unit quantity that can be purchased at a given time. For the equivalent of 0.30 euros, an omena stew can be prepared that feeds two people. This is particularly important during dry spells when agricultural production is low, or fails. Omena is eaten with its bones (calcium) and head (vitamin A). It contains phosphor, polyunsaturated acids and oils such as omega 3 and 6. It is thus not only a valuable source of protein but also provides micronutrients that are particularly important for children and childbearing women.

Clearly defined roles

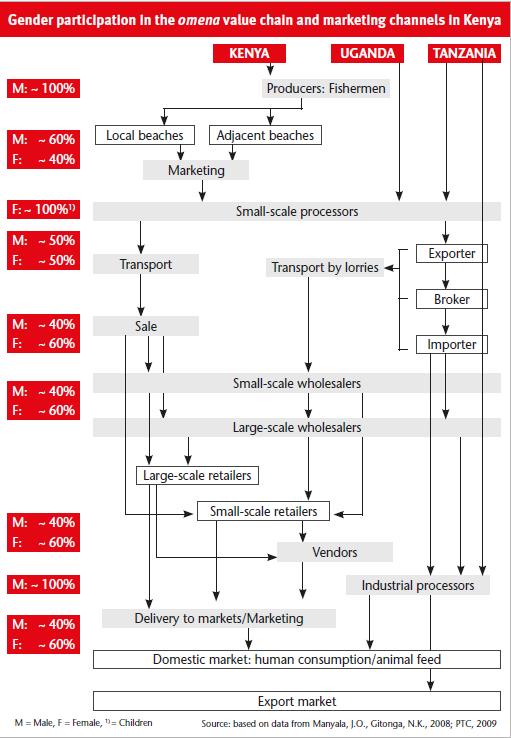

Women have always occupied a central place in Kenya’s fishing sector. However, cultural, social, economic and political factors and a high rate of illiteracy amongst women in fishing communities account for their marginalisation and their being given little attention in fishing. As shown in the Figure below, the omena fishery value chain includes men, women and children. Fishing, including ownership of boats (3,000 boats targeting omena) and gear, as well as industrial processing is mainly dominated by men (30,000 fishermen). Women, however, dominate the onshore post-harvest sector and are the main actors for small-scale processing (800,000 women). Transporting, marketing and sale is shared by men and women, with women accounting for the larger share.

Omena is caught by fishermen and landed at the lake site where it is mainly sold to women. However, the downside of this trade is that due to the high competition amongst buyers, the traditional jaboya – originally referring to a business partner in the fishery community – lead to a type of prostitution in kind. The main vulnerable victims are single women, divorced women and widows. The ‘sex for fish’ practice is thought to have contributed to the HIV/AIDS pandemic in the Lake Region (where prevalence rates are twice as high as in the rest of the country).

Post-harvest processing, i.e. the washing and sun-drying of fish on nets or on the ground, is almost exclusively done by women; children are also frequently involved in this business. In 2011, fresh omena was sold for 0.30 euros per kg, and after drying its price rose to 0.50 euros per kg depending on the quality and market demand. Today, prices of 0.90 and 1.30 euros per kg for fresh and dried omena respectively can be obtained at Kenya’s markets. Approximately 20 euros is needed to start an omena drying business that provides a daily income. It is therefore very accessible for women who are landless and often widowed and have little, if any, access to credits.

Sun-dried fish is favoured by the women as it provides choice of time and place for marketing, thus avoiding competition with their other chores. Its end-use for human consumption or animal feed (mainly chicken) depends on the quality. Rejections are mainly due to dampness, presence of debris, discolouration and the presence of freshwater shrimp (Caridina). The reasons for these shortcomings include the lack of adequate landing and processing sites, use of polluted lake water to wash the fish, and insufficient drying during the wet season.

Value chain development

In order to counter these shortcomings, the German Corporation for International Development (GIZ), on behalf of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ), and the Ministry of Agriculture, Kenya, started to implement the development of the omena fish value chain as a component of the ‘Private Sector Development in Agriculture’ (PSDA) programme. By 2008, the initiative had reached 5,000 households of Kenyan fishermen, women processors and traders. The main objectives were the formation and strengthening of market-oriented fishermen and traders groups and associations, and capacity building of the respective members and officials.

In total, three associations were formed and registered. Fishermen and traders were equipped with the necessary skills to improve quality, conditions of marketing for their products and the purchase of inputs. Special attention was provided to women groups to establish hygienic handling and processing and to improve business skills to reduce post-harvest losses and increase profitability. The Umoja Fish Traders Sacco Group in Kisumu is an example of best practice. Supported by the programme, the group improved its financial management and management structure, leading to a doubling of savings to 12,000 euro within two years. These funds are used to grant loans to group members for establishing other commercial activities, or to improve their omena business.

Overall, the omena value chain component resulted in increases of 15 to 20 per cent in income for producers, processors and traders. Better quality (lower humidity, sand and debris-free dried produce) and well-packaged omena yielded economic benefits. It fetched 100 per cent higher retail prices compared to fish commonly processed under unhygienic conditions. Feed millers offered price increases of 50 per cent for quality omena. The higher income led to improvements in livelihood, especially in the areas of education and food security. Additional income was invested in the diversification of economic activities, for example poultry keeping, opening a shop or horticulture.

Moreover, GIZ supported the necessary policy development. Thus, PSDA’s interventions have resulted in an increasing collaboration and networking between stakeholders of the omena fish value chain and their organisations, for example the Lake Victoria Omena Fisherman and Traders Association (LOFTA). The results-oriented linkages between public and private stakeholders of the omena value chain were assured through the formation and regular meetings of a value chain committee. The linkages established helped to develop trust, partnership, and information exchange.

To sum up …

The programme contributed to improving the livelihood of people depending on omena and the omena value chain in Kenya. One success is the incorporation of value chain development in Kenya’s agricultural policy. The proportion of higher quality omena was also increased in the project region. For example, the feed industry responded with a 50 per cent increase in price for higher quality omena, i.e. free of sand. However, the women rejected drying on raised racks, opted for initially to further improve hygienic processing conditions. The expected rise in sale prices for such produce did not happen; hence additional investment costs were not accepted locally. Thus, in the context of the project, traditional air drying on old nets, but with improved hygiene standards (through washing) and reduced impurification (e.g. through sand or stones) was advocated. The development of construction options that use cheaper yet effective and durable materials or support from the public and private sector to access affordable drying racks may help to arrive at locally accepted solutions. Efforts are still needed to further improve the hygienic handling and processing regulations and standards. There continues to be a need to strengthen the role of women in the value chain. An inventory of fishing infrastructure and equipment carried out in 2014 revealed that 1.2 per cent of all fishing boats were owned by women. Although it is too early to predict a trend, it seems as if women are now entering the traditionally male-dominated sector of omena fishery.

Mecki Kronen

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale

Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH

Eschborn, Germany

mecki.kronen@giz.de

Arnoud Meijberg

Consultant

Nairobi, Kenya

meijberga@gmail.com

Ines Reinhard

GIZ GmbH

Eschborn, Germany

References and sources for further reading:

GIZ, Republic of Kenya, 2010: Growing value. Achievements in value chain promotion for omena fish value chain in Kenya.

Manyala, J.O., Gitonga, N.K., 2008: A study on marketing channels of omena and consumer preferences in Kenya. GTZ, Republic of Kenya, PSDA, Nairobi, Kenya.

PTC, 2009: Inception report for consultancy on mapping out gender related interventions in Kenya’s agricultural sector. GTZ, PSDA, Nairobi, Kenya.

Kamau, P. and Ngigi, S., 2013: Potential for women traders to upgrade within the fish trade value chain: Evidence from Kenya. DBA African Management Review, August 2013, Vol. 3 (2): 93-107.

LVFO, 2011: Technical report: Stock assessment Regional Working Group, 22-25 November 2011. Lake Victoria Fisheries Organisation. Seeta, Uganda.

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment