Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Capacity development for agricultural policy advice

Global agricultural markets have experienced major shifts during the past years. The era of low agricultural prices came to an abrupt end in 2007/08, with the historic price spikes for major food crops. As a result, agriculture as a sector is now receiving much more attention from policy-makers in many countries, particularly in developing countries. Ideas about agricultural development have changed significantly and a revival of interest in stimulating the sector via active policies can be observed. This requires developing country policy-makers to reconsider their role, policy objectives and instruments as much as it requires development agencies to re-think their capacities to advise on agricultural policy topics and processes.

Yet, most international agencies that provide agricultural policy advisory services work with staff who were educated at a time when agricultural economics and rural development were taught differently. For example, the strong credo for liberalised and deregulated markets as an outcome of the ‘Washington Consensus’ resulted in a generally reluctant position towards state interference in agricultural markets. See also Agricultural policies in the 2010's: the contemporary Agenda.

But since the agricultural world is changing, so are the challenges in policy advisory work. Governments tend to (again) pursue a much more active role in agricultural markets, e.g. by implementing subsidy schemes or food price stabilisation. A critical look at advisory skills is important in order to better equip the staff of international agencies to provide adequate advisory services for agricultural development today and in future.

The contemporary capacity agenda

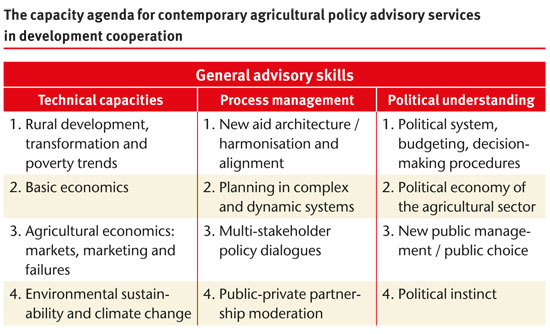

In 2012, GIZ on behalf of the German Federal Ministry for Development and Economic Cooperation (BMZ) initiated a discussion process with colleagues and international agricultural policy experts to assess the portfolio of countries where German Development Cooperation is involved in agricultural policy advice and to scrutinise the topics and processes advisors are involved in. What are the topics and instruments for development-oriented agricultural policy-making? What are the challenges and opportunities to support its implementation? And what advisory capacities are needed to deliver substantive advice to developing countries’ governments? The answers to these questions constitute the contemporary capacity agenda for agricultural policy as depicted in the graph below and are outlined below.

General advisory skills

Above all, a set of overarching and more general advisory skills have to be highlighted as a necessary precondition for any successful advisory services. These include intercultural communication skills and a general “analytical mindset”. Modern concepts of advice and extension have evolved from a pure delivery of technical solutions to technical questions to a much more process-oriented interpretation of the role of advisors as “trusted acquaintances”, who help navigate through rather stormy policy processes. These necessary general skills are not further elaborated here; however, as they play a key role in enabling an advisor to establish a trustful relationship with the individuals and institutions he or she is advising, they are of utmost importance. Regular training or coaching can keep these skills afresh and help developing increased advisory capacities. In addition, colleagues state that important advisory skills are gained by working under good leadership, learning from inspiring examples and developing personal experiences. In addition to such general skills, three sets of different skills are necessary to meet the increasing challenges to agricultural policies: (1) technical capacities, (2) process management, and (3) political understanding.

Technical capacities

Acquaintance with technical subject matters is seen as absolutely crucial to the credibility of any advisor and is usually valued very highly among most individuals and institutions that seek advisory services. Therefore, it is important to map out the necessary technical capacities for contemporary agricultural policy advisory services, since they have widened over the past decade. The first area constitutes the ability to assess the general rural development trends of a country or region using modern methods and parameters of various disciplines such as poverty analysis, household demography, social security, migration patterns, resource use, property rights, the analysis of the non-farm rural economy and assessing the status of structural rural transformation.

Secondly, advisors need to have basic economic knowledge to understand the macro-economic situation and trends for the country and their impacts on the agricultural sector, including public finances, inflation, terms of trade, tax base and savings and interest rates. They should also be familiar with growth economics, including the role of public goods and investment, technology, factor accumulation, human capital and the labour market.

Agricultural economics is almost needless to mention as a key area of knowledge. Today, sound agricultural economic analyses require proficiency in the following four areas:

- a profound understanding of agricultural markets and the factors driving supply and demand (on the supply side, this includes farm economics and the ability to assess gross margins for agricultural produce; on the demand side, it implies a thorough understanding of price and income elasticities of demand and the integration of rural and urban as well as domestic, regional, and international markets);

- a clear understanding of the value chain concept developed over the past decade and agricultural marketing;

- an understanding of causes and effects of prevailing market failures in agricultural markets;

- an understanding on the role technology can play in changing agricultural economics in terms of factor production and returns to research and extension.

Lastly, a contemporary agricultural policy advisor will not be able to do good work without some basic knowledge of environmentally sustainable agricultural production amidst climate change. Sustainable intensification and land use changes will dominate much of agricultural policies in future. Anticipating changes in production patterns and helping to prepare options for either adaptation to climate change or mitigating risks and vulnerability, particularly in marginalised areas, will become a major task for development co-operation in the years to come.

Process management

The importance of the capacities summarised as “process management skills” has definitely increased over the past years, namely after the release of the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness in 2005 and its follow-ups, such as the Accra Agenda for Action and the Busan Partnership Document. The new aid architecture requires developing country governments and all involved development partners, and hence advisors, to consult, collaborate, cooperate, align and harmonise their activities much more than before. In a number of countries, the frameworks under which aid programmes operate have changed into sector-wide programming, programme-based approaches or even budget support. All such modes of delivery require participation in new forms of policy planning and dialogue forums. Advisors therefore need to understand the limits to linear planning and the importance of flexibly engaging in policy planning processes at national level in ever more complex and dynamic agricultural sector debates.

To succeed in policy process management, the facilitation of multi-stakeholder dialogues is becoming ever more pertinent. With democratisation, agricultural policy processes in many countries today require widespread and inclusive participation of different stakeholders. For Africa, the emergence of the NEPAD Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Plan (CAADP) came with an additional need for new co-ordination mechanisms at country level. Many advisors are faced with the task of supporting public sector actors in managing the moderation of such multi-stakeholder processes that include farmer organisations, private sector actors and civil society organisations. They are requested to provide thoughts on “how to do this” for developing country government representatives, who often lack the experience in engaging effectively with non-state actors. This holds particularly true for the moderation of public-private partnerships along agricultural value chains. Many developing country bureaucracies lack experience and opportunity in partnering effectively with private sector actors. Whereas many prejudices prevail on both sides, policy advisors can act here as brokers and facilitate the two sides to work together for results. They can offer a third party in such partnerships and thus need good negotiating skills and a deep understanding of rationales of both the public and the private sector.

Political understanding

It might sound self-evident, but it is important to stress this third set of crucial skills: advisors need to understand the political system they are operating in. More than often, decision-making in agricultural policy depends to a lesser extent on technical evidence, but on the power and leadership of involved individuals, institutions, and interest groups. Advisors need to understand the mechanisms of formal policy-making as well as the informal values and principles that dominate policy and decision-making processes. Here, a comprehension of policy choice as discussed in contemporary political economy literature is necessary. Advisors need to understand the motivations and incentives of key actors: this might be ranging from agribusiness actors exercising pressure to influence markets or to obtain subsidies; to politicians, who need to weight the implications for power and stability; to the ideals of equity and justice found among NGOs; up to other donors and their institutional interests and incentive structures. Such are the complexities (and potential fallacies) in the above-mentioned multi-stakeholder processes. There are no blueprint ways of advising under such circumstances, however it is important to contemplate that engaging in such policy processes requires advisors to think and work politically. This means understanding the politics at national level as well as politics of international development.

As for public administration, advisors need to know basics of the theory and practice of public management. When working within bureaucracies, knowledge of the theory of bureaucracy, organisational development and change management are essential. The same applies to decentralisation (and its variants, such as deconcentration processes as they are increasingly enfolding, particularly in a number of African states).

Lastly, advisors need to develop a sense for political timing and opportunities in their given work environment – what colleagues call “political instinct”. Development co-operation is increasingly involved in rapidly changing societies. Changes in governments often provide unique dynamics and windows of opportunities. To prepare the individuals and institutions you are advising for quickly seizing such political opportunities can make a real difference in outcome. As much as the term “instinct” might sound like a congenital feature, it is far more of a skill acquired over time with ears and eyes wide open and the analytical senses sharpened.

Some final reflections

This contemporary capacity agenda for agricultural policy has resulted in an arguable long list of desirable skills which needs to be validated against the real world people constituting the staff who work as advisors and consultants. The agenda set out is deliberately broad, since advisors need to appreciate technical, procedural and political considerations, if they are to provide informed advice. To be effective, advisors need theories, concepts, and specific technical knowledge at equal share. Had this been written thirty years ago, technical skills might have been given a higher weight. The shift in emphasis probably reflects the awareness that agricultural policy decisions are embedded in complex sector processes that equally need “procedural cleverness and endurance” and technical inputs alike.

How to do it? A way forward

The GIZ Sector Project “Agricultural Policy and Food Security”, on behalf of BMZ, is leading a process to discuss this capacity agenda together with partners from developing countries, project staff, other agencies, consultants, intermediaries and private sector players. One element here is to implement capacity development activities for agricultural policy advisors and their partners in the field. Classical training courses will form part of this, however human capacity development (HCD) can draw on a much wider set of learning and knowledge instruments (see Box below).

Human capacity development

Human capacity development (HCD) develops individual capacities and shapes learning processes in four areas:

- Personal and social skills

- Technical expertise

- Managerial and methodological capacities

- Leadership skills

The aim is to enable advisors or partners to extend their individual capability base so that they can draw on comprehensive skills and knowledge when making policy decisions. GIZ offers generic trainings in these four different areas as well as tailor-made learning formats.

➤ www.giz.de/en/ourservices/270.html

A sometimes simpler and less costly way to gain knowledge is through learning from experience by monitoring and evaluation of advisory practices, the documentation of insightful case studies and effective dissemination of results. More so, our current thinking for enhancing agricultural policy advisory skills embraces mechanisms for peer-learning in institutionalised networks and on-the-job learning events, e.g. within the scope of GIZ’s sector network working groups. Instead of singular donor efforts, German Development Cooperation is encouraging networking between European development organisations and agencies in order to build international alliances to develop the necessary capacities within development agencies and, more importantly, in the developing countries that need to politically manage the agricultural complexities and challenges ahead.

Further reading

This article is based on discussions held during GIZ Sector Network for Rural Development (SNRD) meetings in Africa and Asia in 2012 and 2013 as well as on the Expert Meeting “Agricultural policy for development: a fresh look at policy options, instruments and roles for governments, private sector and development agencies” held in Bonn in December 2012;

An extended version of this skills debate can be found in the ODI-GIZ Background Paper by Steve Wiggins et al. (2013) Agricultural development policy: a contemporary agenda, Chapter 4;

A commendable evaluation of policy dialogue capacities has been undertaken by Australian Aid: Thinking and Working Politically;

see www.ode.ausaid.gov.au

Heike Höffler

GIZ Sector Project “Agricultural Policy and Food Security”

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale

Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH

Bonn, Germany

heike.hoeffler@giz.de

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment