Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Linking smallholders to organic supply chains: what is needed?

Organic production is particularly well-suited for smallholders as it makes them less dependent on external resources and able to rely on their traditional knowledge. Smallholders who have shifted to organic production and marketing enjoy higher and more stable yields and income, thus enhancing their food security. However, their products have to be certified by specialised agencies in order to be sold under the “organic” label and thereby obtain premium prices. This is usually costly and cumbersome for smallholders in the developing world.

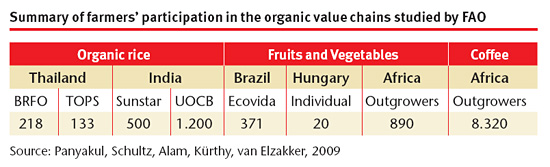

An FAO study (Santacoloma, 2007) showed that alternative organic certification schemes are embedded in particular market relationships that determine specific business and technical services, inputs and post-harvest needs for the actors in the chain. Building upon these findings, FAO further investigated marketing strategies and sources of financing of support organisations for the future fostering of the organic sector in developing countries. It studied organic ventures in rice in Thailand and India, coffee and fruits from African countries and horticulture products in Hungary and Brazil.

The market for organic products

The international markets for organic products continue to grow at a rapid rate of 10 to 30 per cent per annum in most countries and at a rate of over 5 billion US dollars (USD) per year globally, with fresh fruits and vegetables being the leading sector. Organic vegetables comprise over five per cent of all vegetable sales in northern European countries and exceed ten per cent in some Scandinavian and Alpine countries. The organic fruit market is reporting an even higher growth as more tropical and exotic varieties come into the market.

The global market in 2009 for organic food and drink rose to over 54.9 billion USD, with the vast majority of products being consumed in North America and Europe. Domestic markets for certified organic products in developing countries are much less developed, with the exception of China. Nonetheless, the potential for strong exchange between countries in an emerging, regional Asia-Pacific organic market is consolidating an organic industry that had originally developed to supply countries in the West. While organic premiums are high in a few export or domestic markets, there are some concerns that these may not last, as more and larger commercial producers are entering this market and consequently prices may fall in the future.

Organic supply chains

Across the study, supply chains range from very short ones where farmers market directly to local consumers, to more elaborated chains where a number of different actors are involved in moving the organic products from the farm to the final consumer while keeping the organic quality attribute. Some models are:

Farmer to consumer chains: These are very popular for producers associated with the agro-ecological movement in Brazil, who sell their products at marketplaces or ecological fairs provided by municipal governments. Prices are established through producer-group negotiation with the local municipalities and state government bodies who are responsible for the fairs. In Hungary, small organic farmers also market directly to consumers through organic public marketplaces.

Farmer to retailer or supermarket chains: In Thailand, the private retailing company TOPS markets organic produce under its own brand in its supermarkets located around the country. Rice, coconut, milk, coffee and shrimps are some of the organic products marketed under the TOPS brand. Similarly, in Brazil, organised producers collectively sort and pack fresh and processed products for shipping to supermarkets and retail stores directly.

Farmers to food processor chains: In the two basmati rice cases in India, farmers supply their paddy to a rice mill and the processed rice is shipped in bulk or filled into retail packs before exporting. In the former case, a private company organises the supply chain. A federation of farmers produces the organic rice under contract, and the company transports, processes, packages and distributes the product to domestic markets as well as to export fair-trade and organic markets in Europe. In the latter case, a state controlled commodity board arranges the production with farmers and negotiates contracts with the main buyer, who processes the rice at his own mill and packs and transports it to domestic and foreign markets.

Farmer to importer: In the case of African organic coffee, coffee cherries are cultivated by farmers, harvested and brought to a collection centre, where they are pulped to separate the beans. The beans are then dehulled and dried. Some of these operations may be also done on farm. Subsequently, the beans are bagged and exported directly to the importer. In some cases, the beans may be sent to an exporter, who will grade and repack before shipping to the importer, who will roast or sell on to the roaster and packer for retailing.

In the majority of the cases in the FAO study, the market opportunity was identified by the entrepreneur, business or exporter, who set up the business and established the supply chain to exploit it. In only a few cases did the farmers themselves initiate the establishment of the supply chain to fulfil a market demand. In a small number of cases, the supply chain and market link was actually initiated by a government or non-government organisation as a means of promoting organic farming as a smallholder alternative.

Organic quality attribute along the chain

In any agro-food chain, the maintenance of product quality from the farm to the consumer is paramount for achieving good prices and sustainable business. This means that transportation and logistics of the harvested product are important components of the supply chain. Organic products have additional demands in that handling, transportation, storage and packing must be done under certified conditions and segregated from non-organic products. Therefore, once the product leaves the organic farm, transportation and handling facilities must meet these requirements. More recently, traceability has become increasingly required by export markets as a means of ensuring product quality all along the chain. This places additional demands on producers, processors and market agents for organic products aiming at export markets.

With respect to infrastructure, there are two major issues in the cases reviewed. Firstly, the individual farmer does not have the resources to invest in transport, storage or processing facilities in order to provide good quality products for the market. Therefore, the trend has been to form farmer groups who can establish a collection centre or a group packing facility and organise transportation of the products to their processor, exporter or directly to the consumer. In some cases this has been extended to processing such as rice milling (Thailand, India), coffee dehulling (Africa), fruit juice processing (Brazil, Africa), fruit drying (Africa) and even retail packing of products (Africa, Brazil, India, Thailand). Generally, however, processing, storage and trucking are handled by the private sector entrepreneur, wholesaler or exporter.

In short, the organisation of the organic supply chain does not differ much from the conventional chains. However, to maintain the organic quality attribute, stronger vertical coordination, logistics and infrastructure are required, as well as clearly defined actors roles and responsibilities. By forming groups, certification costs can be lowered and efficient procurement practices fostered.

Financing mechanisms

Setting-up and operating an organic production chain requires substantial financial resources, which are often beyond the means of small farmers and their organisations. They must rely on partnerships with buyers and other actors to finance their participation. Formal credit and loans with commercial banks and government programmes generally have no special component for organic farming operations, with the exception of Hungary with its links to the EU programmes, and Thailand and Brazil, where specific financing mechanisms for community organisations and family agriculture favour organic farmers. In general, farmers do not seek financing from commercial banks, due to their high interest and collateral demands. They prefer to rely on their own resources or borrow informally.

Private sector partnerships were the key source of financing for the organic supply chains. Their finance came from personal or internal sources and in some cases from commercial banks. In other cases, fair-trade partnerships between producers and buyers in developed countries were able to reliably finance production and post-harvest operations, through the provision of advance payments. However, in some cases this was not sufficient to pay for all the harvested crops, particularly in the case of rice. Consequently farmers’ organisations still have to find more funds locally.

In short, financing of crop production for smallholders continues to be problematic in developing countries, whether the product is organic or not. Where private sector or fair-trade type partnerships are being developed or are functioning, it would be desirable that commercial banks and government-backed programmes be encouraged to develop appropriate financing mechanisms that will facilitate smooth functioning of all essential activities along the supply chain.

Proposals to enhance smallholder’s participation in organic chains

Governments should promote an enabling environment to facilitate the development of organic supply chains for both export and domestic markets. This will require expanding extension services to include organic production techniques and post-harvest operations, developing credit lines for conversion and certification costs, and support for training in food safety and quality management, business management and associated consulting services from local private suppliers.

Governments should also promote organic products for domestic consumption through the development of organic marketplaces in partnership with municipalities and by furthering the procurement of organic products for public sector health, food and nutrition programmes.

Partnering companies should identify market opportunities in domestic or overseas markets before participating in or developing organic supply chains. Companies must also ensure they have the human and financial resources to champion the development and operation of the organic supply chain.

Financing institutions are encouraged to develop appropriate financing mechanisms that will take into account the particularities of organic production such as the conversion period and product segregation along the chain.

Support groups such as NGOs who work with small-scale farmers in organic projects should ensure that they have the capacity to deal with post-harvest, food safety and quality, finance, marketing and business management activities through their own staffing or through alliances or sub-contracts with specialist groups.

References:

Working papers by Alam, Ghayur, Kürthy, Gyöngyi. Panyakul, Vitoon Schultz, Glauco van Elzakker, Bo for AGS, FAO, Rome 2009 (unpublished).

Alam, Ghayur, 2009. Appraisal of financing mechanisms, marketing strategies and value-adding opportunities in the organic sector as tools for enhancing farmers’ income-generation: a Study of Organic Basmati Rice in Uttarakhand, India. Paper prepared for AGST, FAO, Rome (unpublished).

Cadilhon, J.-J. 2010. The market for organic products in Asia–Pacific. Proceedings of BioFach China Conference on International Organic Food Markets and Development. China Agricultural University Press, Beijing, pp.137-150.

IFAD, 2005. Organic Agriculture and Poverty Reduction in Asia: China and India Focus. Thematic Evaluation. Report No. 1664. Rome.

Kürthy, Gyöngyi. 2009. Appraisal of financing mechanism, marketing strategies and value-adding opportunities in the organic sector as tools for enhancing farmers’ income generation. Paper prepared for AGSF, FAO, Rome (unpublished).

Organic Monitor, Research News, August 13th, 2010 – The European Market for ethical fruits and vegetables.

Panyakul, Vitoon. 2009. Appraisal of Financing Mechanisms and Marketing Strategies in the Organic Sector as Tools for Enhancing Farmers’ Income-Generation. Thailand Case Study. Paper prepared for AGSF, FAO, Rome (unpublished).

Santacoloma, P. 2007. Organic certification schemes: managerial skills and associated costs. Agricultural Management, Marketing and Finance Occasional Paper 16, FAO, Rome.

Schultz, Glauco. 2009. An evaluation of marketing strategies, financing sources, value adding opportunities for organic production in Brazil – A case study in Rede Ecovida de Agroecologia (unpublished).

UNEP-UNCTAD Capacity Building Task Force on Trade, Environment and Development. 2008. Best Practices for Organic Policy. What developing country Governments can do to promote the organic agriculture sector. United Nations. New York and Geneva.

van Elzakker, Bo. 2009. Increasing incomes of smallholder farmers from organic export agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa – based on coffee and pineapple. Paper prepared for AGSF, FAO, Rome (unpublished).

Willer, Helga and Kilcher, Lukas (Eds.) (2011) The World of Organic Agriculture - Statistics and Emerging Trends 2011. IFOAM, Bonn, and FiBL, Frick.

Pilar Santacoloma

Agribusiness economist Rural Infrastructure and Agro-industries Division

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO)

Rome, Italy

Pilar.Santacoloma@fao.org

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment