Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

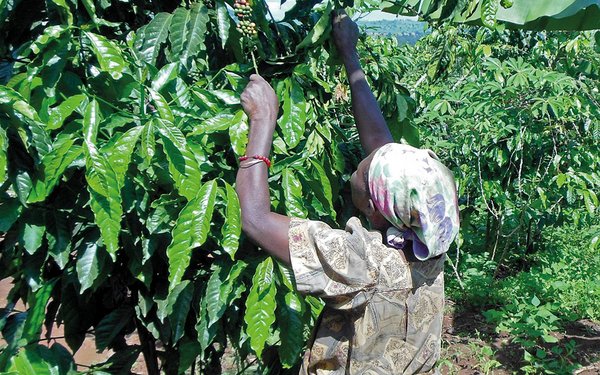

Do smallholder farmers benefit from sustainability standards?

Millions of farmers are certified under sustainability standards such as Fairtrade (about 1.65 million), UTZ (about 1 million), Rainforest Alliance (about 1.2 million) and Organic (about 2.3 million). Sustainability standards are gaining in importance especially for higher-value foods from developing countries (also see Box at end of article). The development for certified coffee, cocoa, palm oil and tea is particularly remarkable. An estimated 30 per cent of the global coffee area, 20 per cent of the global cocoa area, 15 per cent of the global palm oil area, and 9 per cent of the global tea area are certified under different sustainability-oriented standards.

The proliferation of sustainability standards and related certification schemes in developing countries is attributable to different factors. Stand-ards address food quality and safety, environmental and human rights, and welfare issues along agricultural value chains. An increasing number of consumers, especially in developed countries, are concerned about such issues. More importantly, many consumers are willing to pay more for certified products with a sustainability label. Further, development agencies have played a key role in facilitating farmer adoption of sustainability stand-ards. Increasingly, private retailers and manufacturers also evolve as important players. For instance, Starbucks sell Fairtrade and Organic coffee in their stores and have developed their own sustainability standards (C.A.F.E. Practices). This boom in standards and certification will likely persist, given continued interest in sustainable approaches to global food production and trade.

Can poor farmers meet sustainability standards?

Farmers who want to join a particular standard have to go through a certification process and regular audits. Certification and audits are carried out by specific agencies and serve to ensure that rules on environmental and social issues are met. This process can be bureaucratic and costly (i.e. costs can sum up to several thousand euros, depending on the sustainability standard and production volumes). These costs are usually too high for individual farmers. Consequently, in the developing-country small farm sector, certification is predominantly group-based. Group certification reduces administrative and financial certification costs for individual farmers. Group structures also facilitate the implementation of training sessions and other support measures.

Without such support, farmers would find it hard to meet some of the certification requirements. Specifically, standard-compliant production can require financial investments, managerial skills and a switch to more labour-intensive farming practices. For example, if standards require farmers to use protective gear during pesticide application, such equipment may have to be purchased. Quality requirements may presuppose investments in equipment to properly dry, process and store the harvest. Training offered to farmer groups, collective use of equipment and credit schemes can help farmers to better understand and meet certification requirements. Governmental and non-governmental development agencies often help farmers to organise in groups, pay for certification costs, and implement related training sessions.

Do sustainability standards raise farmers’ incomes?

Whether farmers benefit from sustainability standards is discussed controversially. Opponents of the standard boom argue that the price markup that consumers have to pay for sustainability-labelled products hardly reaches smallholders in developing countries. Proponents, on the other hand, sometimes argue that sustainability standards are the only way to increase fairness in international value chains and thus improve farmers’ incomes.

None of these extreme views is compatible with the scientific evidence. A growing number of studies examine if farmers benefit from sustainability standards. Available studies differ in terms of their methods used. The most reliable ones are those that compare certified and non-certified farmers while controlling for other factors that may bias this comparison (e.g. differences in education). A comprehensive review of the evidence suggests that sustainability standards are neither a silver bullet for poverty reduction nor an empty promise. A few more insights are summarised in the following.

For farmers, the adoption of sustainability standards is associated with costs and benefits. Cost aspects were already discussed above. On the benefit side, certified farmers often receive higher output prices. Yet, in some cases, they cannot sell their entire harvest in certified value chains. This happens when too many farmers in the same region produce certified crops. Another benefit is that certified farmer organisations usually offer agricultural trainings and other services to their members. This can be important especially in areas where general access to extension is limited. Standards can also provide mechanisms for farmers to improve productivity and product quality. For instance, environmentally-friendly farming practices such as erosion measures or intercropping can improve soil fertility, and thus yields.

The overall impact of sustainability standards on farmers’ income is context-specific. Many studies looking at examples in Africa conclude that standards help to raise income. For Latin America, results are sometimes less positive, especially in the coffee sector. Contrasting findings can partly be explained by regional differences. In Africa, coffee is typically produced by very small farms with poor access to agricultural inputs and extension. In such situations, sustainability standards can have positive yield and income effects. In Latin America, access to agricultural technology and services is often better, so that the additional benefit of standards is less pronounced.

Beyond geographic differences, income effects can also vary by type of standard. For instance, yields may be lower under Organic, because chemical pesticides and fertilisers are banned. Hence, a larger price premium is required in order to compensate for lower quantities.

Do sustainability standards promote development goals beyond higher incomes?

Studies typically look at the effects on farmers’ income. This is not surprising, because one of the key goals of sustainability standards is to improve incomes of poor farm households. However, from a broader welfare perspective, it is important to understand whether sustainability standards can also serve to promote development goals beyond a narrow income focus. Studies have analysed the effect of sustainability standards on child education, food and nutrition security, and gender equality, with promising results.

Our own team at the University of Göttingen has analysed the impact of Fairtrade standards on child education among smallholder farmers in Uganda. We found that Fairtrade households invest 146 per cent more in child education than non-certified households. Controlling for age and other factors, we also showed that children in Fairtrade households spend on average 0.66 years longer in school than children in non-certified households. The positive effect of Fairtrade certification on child education is partly linked to higher incomes, but other mechanisms also play a role. Specifically, Fairtrade includes specific rules and activities to reduce child labour and to raise awareness on the importance of education.

In another study, we have shown that Fairtrade and UTZ standards promote women’s empowerment through awareness building and special training sessions on gender equality. For example, certification does not only increase household wealth – it also alters the distribution of wealth within households. In non-certified households, male household heads own most assets. In contrast, in certified households most assets are owned jointly by couples. Further, certified farmers have better access to agricultural extension, irrespective of their gender. We have also evaluated effects of Organic certification among smallholder coffee farmers in Uganda and found positive effects on household nutrition and dietary diversity. These effects cannot be generalised, but they suggest that sustainability standards can improve various dimensions of household welfare, when properly designed and implemented.

What do farmers think about sustainability standards?

Adopting a standard and entering into a certification scheme may seem burdensome and complicated from the farmers’ point of view. In a recent study, we examined farmers’ subjective attitudes. We found that they have positive attitudes towards sustainability standards in general. An output price premium is a strong incentive for farmers to adopt a standard. But our study shows that they also appreciate the provision of training, credit and other services. Interestingly, farmers are willing to accept requirements on product quality, farm management and occupational safety, even without being compensated through a price premium. They are aware of the fact that such requirements can help them to increase productivity and efficiency in the longer term. However, farmers dislike bans of chemical pesticides and other productivity-enhancing inputs. Such bans are only accepted with a significant price premium as compensation.

Should development aid be spent to promote farmer adoption of sustainability standards?

Whether or not sustainability certification is a suitable and beneficial option for farmer organisations should be decided case by case. In such assessments, the following questions need to be addressed: Is the farmer organisation capable of managing a bureaucratic and costly certification process? How will the demand for the particular product develop? To what extent can certification improve farmers’ access to agricultural services in the region? How strongly will ecological farming practices affect productivity in the particular context? Further, a careful assessment of the different sustainability standards is crucial, as these vary in terms of their stringency and specific requirements. A ‘one-fits-all’ solution does not exist.

Goals and requirements of sustainability standards

The number of sustainability standards is constantly increasing. There are now over 200 different standards with a focus on sustainability. The first of them emerged from civil society initiatives (e.g. Fairtrade, Rainforest Alliance or Organic). In contrast, newer standards were often set by multi-stakeholder initiatives such as the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO). Sustainability standards intend to promote sustainable development and typically include rules related to environmental and socioeconomic issues. Standards vary in terms of their specific focus and requirements. For instance, Fairtrade places emphasis on social issues, promoting democratic structures of farmer organisations, prohibiting child labour, and requiring the safe handling of agrochemicals. Organic and Rainforest Alliance place greater emphasis on environmental aspects. For example, under Organic, chemical pesticides and fertilisers are prohibited and ecological farming practices are promoted. UTZ addresses both environmental and socioeconomic issues. Compared to several other standards, UTZ also has higher product quality demands, such as particular rules on post-harvest handling. Standards set by multi-stakeholder initiatives (like RSPO) often have less stringent standards in general.

More information on voluntary sustainability standards and other similar initiatives covering issues such as food quality and safety is available at: www.standardsmap.org

Eva-Marie Meemken

Research Associate

Department of Agricultural Economics

and Rural Development

University of Göttingen, Germany

eva-marie.meemken@agr.uni-goettingen.de

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment