"We have never been in a better position to end the pandemic"

Ms Drysdale, what is the current trend globally concerning Covid-19 infection?

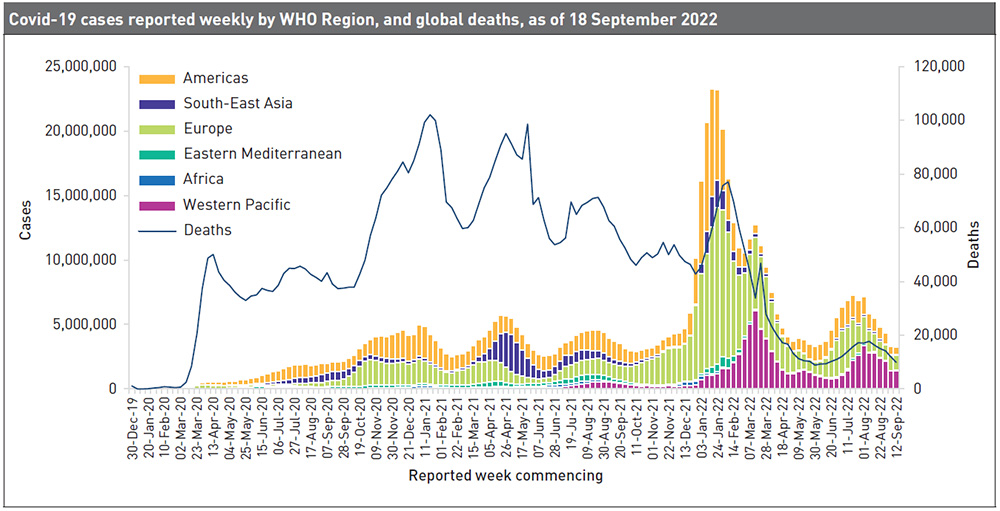

Carla Drysdale: We are seeing a continuing trend of declining numbers of weekly deaths, so as of September 22nd, they are just ten per cent of what they were at the peak in January 2021. Globally, the number of new weekly cases remained stable during the week of the 12th to the 18th September 2022 as compared to the previous week, with over 3.2 million new cases reported. The number of new weekly deaths decreased by 17 per cent as compared to the previous week, with more than 9,800 fatalities reported. As of the 18th September 2022, over 609 million confirmed cases and more than 6.5 million deaths have been reported globally. At the regional level, the number of newly reported weekly cases decreased or remained stable across all six WHO regions. In many countries, restrictions are gone, but let's pause for a moment and remember that we are still seeing 10,000 deaths per week, which is a sobering statistic. Especially when you consider that most of those deaths could have been prevented.

WHO had demanded that by 2022, at least 70 per cent of the world population should be vaccinated against corona. How close have we already got to this goal?

Drysdale: As of the 5th September 2022, 32 per cent of the world’s population have still not received a dose of Covid-19 vaccine. While 63 per cent of the total population across WHO Member States have completed their primary vaccination, only 18 per cent of people in lower-income countries (LICs) have. And out of 194 WHO Member States, eleven have vaccinated less than ten per cent of their populations and 63 less than 40 per cent. Thanks to the vaccinations performed in WHO Member States, an estimated 19.8. million fatalities were prevented in 2021. However, there is still much left to do. Three-quarters of the world’s health workers and over-60s have been vaccinated, but the global numbers mask huge disparities between regions and income groups. The most at-risk groups are not optimally protected everywhere: for instance, LICs have vaccinated just 23 per cent of their elderly population, and on average, in these countries, just 37 per cent of healthcare workers have been vaccinated.

What has to be done here to improve the situation?

Drysdale: WHO calls on all countries that have not yet reached 100 per cent of health workers, over-60s and everyone at increased risk to do so with extreme urgency and to ensure that these populations receive booster doses per WHO recommendations. This is the most effective way to save lives, strengthen immunity, protect health systems and drive a sustainable economic recovery. WHO also asks countries to further proceed by vaccinating all adults to further extend health benefits and protect health systems, hence keeping society and the economy open. Finally, WHO calls on countries to continue building immunity towards the 70 per cent population coverage target for further disease reduction and protection against future risks. Beyond the 70 per cent target, it is crucial that countries continue to maintain overall immunity levels to keep their populations safe. WHO asks all countries that haven’t yet started to roll-out booster and additional doses to do so immediately. Booster doses are essential to maintain the immunity of vaccinated persons and are particularly important for high-risk groups such as the elderly, healthcare workers, pregnant women and the immune-compromised. Globally, WHO continues to advocate for a step-wise population-based approach to rolling out vaccines, with adults receiving vaccines prior to younger populations being considered. WHO is updating the Global Vaccination Strategy, published in October 2021, which laid out the case for the 10 per cent, 40 per cent and 70 per cent targets. The strategy will establish new global goals and priorities to guide countries, policy-makers, civil society, manufacturers and international organisations in their ongoing efforts to respond to Covid-19.

How is WHO now going to proceed here?

Drysdale: WHO’s focus is now two-fold: first to support the countries that are furthest behind to turn Covid-19 vaccines into vaccinations as fast as possible, by working with them to drive uptake by getting vaccines to where people are, and urgently vaccinating those in the highest and high priority groups with a complete schedule. For example, COVAX (COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access) has delivered 14 million vaccination doses since the beginning of August. Second to support countries in preserving primary healthcare systems and to maintain and reduce the impact of Covid-19 on routine immunisation services. Countries need to use all available delivery platforms, including the Chronic Non-communicable Diseases (NCDs), Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (RMNCH) and other programmes, to increase Covid-19 vaccine uptake.

Let’s talk about the side effects on other diseases. What is the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the management of other diseases?

Drysdale: The impact of Covid-19 has been profound for healthcare and with regard to other diseases. To take the example of malaria, the latest World Malaria Report shows there were an estimated 241 million malaria cases and 627,000 malaria deaths world-wide in 2020. This represents about 14 million more cases in 2020 compared to 2019, and 69,000 more deaths. Approximately two-thirds of these additional deaths (47,000) were linked to disruptions in the provision of malaria prevention, diagnosis and treatment during the pandemic. However, the situation could have been far worse. In the early days of the pandemic, WHO had projected that – with severe service disruptions – malaria deaths in sub-Saharan Africa could potentially double in 2020. But many countries took urgent action to shore up their malaria programmes, averting this worst-case scenario.

Are there any further impacts?

Drysdale: The pandemic also fuelled the largest continued backslide in vaccinations in three decades. In data published by WHO and Unicef in July 2022, the percentage of children who received three doses of the vaccine against diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis (DTP3) – a marker for immunisation coverage within and across countries – fell five percentage points between 2019 and 2021 to 81 per cent. Twenty-five million children missed out on one or more doses of DTP through routine immunisation services in 2021 alone. This is two million more than those who missed out in 2020 and six million more than in 2019, highlighting the growing number of children at risk from devastating but preventable diseases.

What was the reason for this?

Drysdale: The decline was due to many factors, including an increased number of children living in conflict and fragile settings where immunisation access is often challenging, increased misinformation and Covid-19 related issues such as service and supply chain disruptions, resource diversion to response efforts, and containment measures that limited immunisation service access and availability.

What impacts has Covid-19 had on the health systems?

Drysdale: In terms of essential health services in general, according to the third round of WHO’s Global Pulse survey, 90 per cent of countries surveyed reported ongoing disruptions. Countries said there were disruptions across services for all major health areas including sexual, reproductive, maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health, immunisation, nutrition, cancer care, mental, neurological and substance use disorders, HIV, hepatitis, TB, malaria, neglected tropical diseases and care for older people. Additionally, even as Covid-19 vaccination has scaled up, increased disruptions were reported in routine immunisation services, not only among children, but also with adults. Findings from this latest survey, conducted at the end of 2021, suggest that health systems in all regions and in countries of all income levels continue to be severely impacted, with little to no improvement since early 2021, when the previous survey was conducted.

What differences by continent can be observed?

Drysdale: Going back to malaria, sub-Saharan Africa continues to carry the heaviest burden, accounting for about 95 per cent of all malaria cases and 96 per cent of all deaths in 2020. About 80 per cent of deaths in the region are among children under five years of age. Regarding immunisations, vaccine coverage dropped in every region, with the East Asia and Pacific region recording the steepest reversal in DTP3 coverage, falling nine percentage points in just two years. And going back to disruptions in essential health services, some variation was seen in the percentage of services disrupted across regions and income groups. Overall, countries in the WHO Region of the Americas reported the highest average percentage of services disrupted in each country (55 per cent in 27 countries versus 28 per cent in 23 countries in the European region) – although these findings should be interpreted with caution, given the varied response rates to the pulse survey across regions.

What are the lessons learnt regarding the Covid-19 pandemic? Are there any new approaches being pursued by WHO?

Drysdale: In light of the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, WHO’s 194 Member States established a process to draft and negotiate a new accord on pandemic preparedness and response. This was driven by the need to ensure that communities, governments, and all sectors of society – within countries and globally – are better prepared and protected, in order to prevent and respond to future pandemics. The great loss of human life, disruption to households and societies at large, and impact on development are among the factors cited by governments to support the need for lasting action to prevent a repeat of such crises. At the heart of the proposed accord is the need to ensure equity in both access to the tools needed to prevent pandemics – including technologies like vaccines, personal protective equipment, information and expertise – and access to healthcare for all people.

Isn’t immense financial support required for all this, especially when you consider low- and middle-income countries?

Drysdale: Financial support is key to achieving this, of course. The new Financial Intermediary Fund (FIF) for Pandemic Prevention, Preparedness, and Response (PPR) will provide a dedicated stream of additional, long-term financing to strengthen PPR capabilities in low- and middle-income countries and address critical gaps through investments and technical support at the national, regional and global levels. The fund will draw on the strengths and comparative advantages of key institutions engaged in PPR, provide complementary support, improve coordination among partners, incentivise increased country investments, serve as a platform for advocacy, and help focus and sustain much-needed, high-level attention on strengthening health systems. The fund is a key measure to fill critical gaps in global defences against epidemics and pandemics. In its technical leadership role, WHO will advise the FIF Board on where to make the most effective investments to protect health, especially in low- and middle-income countries. The FIF was developed with broad support from members of the G20 and beyond. Over 1.4 billion US dollars in financial commitments has already been announced, and more is expected in the coming months. So far, commitments have been made by Australia, Canada, China, the European Commission, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Republic of Korea, New Zealand, Norway, Singapore, South Africa, Spain, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, the United States, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation and Wellcome Trust.

Let’s take a look at the future. What is WHO’s assessment of further developments regarding the pandemic?

Drysdale: WHO’s Strategic Preparedness, Readiness and Response Plan to end the global Covid-19 emergency in 2022 lays out three possible scenarios for how the pandemic could evolve this year. In the worst-case scenario, a more virulent and highly transmissible variant emerges, and people’s protection against severe disease and death, either from prior vaccination or infection, will wane rapidly. Addressing this situation would require significantly altering the current vaccines and making sure they get to the most vulnerable. But based on what we know now, the most likely scenario is that the virus continues to evolve, but the severity of disease it causes reduces over time as immunity increases due to vaccination and infection. Periodic spikes in cases and deaths may occur as immunity wanes, which may require periodic boosting for vulnerable populations. In the best-case scenario, we may see less severe variants emerge, and boosters or new formulations of vaccines won’t be necessary.

What has to be done in concrete terms for the pandemic to come to an end?

Drysdale: Moving forward, and ending the acute phase of the pandemic this year, requires countries to invest in five core components. First, surveillance, laboratories, and public health intelligence need to be stepped up. Second, vaccination, public health and social measures, and engaged communities remain vital. Third, clinical care for Covid-19 patients and resilient health systems must be ensured. Fourth, research and development, and equitable access to tools and supplies have to be maintained, and fifth, coordination is required as the response transitions from an emergency mode to long-term respiratory disease management. If these measures are taken to a sufficient degree globally, what Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said on the 14th September can happen: “We have never been in a better position to end the pandemic. We are not there yet, but the end is in sight. If we don’t take this opportunity now, we run the risk of more variants, more deaths, more disruption, and more uncertainty.”

Carla Drysdale is a Media Officer and Spokesperson for WHO. Since she joined the WHO in 2018, she has also worked as a communications officer in Resource Mobilization, the Global Malaria Programme and in the Department of Communications. Contact: cdrysdale@who.int

Interview: Patricia Summa

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment