The African Continental Free Trade Area – can the milestone live up to its promise?

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) agreement was signed during an Extraordinary Session of the African Union in March 2018 by representatives of 44 out of 55 member countries of the AU. With Nigeria, Africa's largest economy, signing the agreement in July 2019, 54 countries are now backing the declaration, leaving Eritrea the only African country outside of AfCFTA. Once in operation, the AfCFTA will offer a market worth 3 trillion US dollars (in terms of aggregate Gross Domestic Product, GDP) and could potentially cover all 55 countries, making it the largest free-trade area in the world in terms of the number of countries involved. The AfCFTA is a crucial component of the AU's 2063 agenda for the inclusive and sustainable development of Africa. The overarching agreement includes protocols on handling tariffs, non-tariff barriers, rules of origin, intellectual property rights, and dispute settlement.

The current status of AfCFTA

Since January 2021, the AfCFTA agreement is formally effective, but de facto not implemented. Despite the agreement having entered into operation, trade under the AfCFTA has not started until recently. However, different initiatives have been prepared, such as the Guided Trade Initiative (GTI) by a group of eight countries, including Egypt, Ghana, Cameroon, Kenya, Mauritius, Rwanda, Tanzania and Tunisia in October 2022. Under the GTI, 96 products, including agricultural commodities like tea, coffee, processed meat products, corn starch, sugar, pasta, glucose syrup and dried fruits, have been earmarked to trade with AfCFTA rules. These products are not necessarily tax-free. The AfCFTA rules require members to liberalise 90 per cent of their goods until 2030 and another 7 per cent, comprising so-called sensitive products, by 2035. Countries are allowed to choose to tax the remaining 3 per cent of all goods. The launch of the Pan-African Payments and Settlements System (PAPSS) in January 2022 was also an important step to facilitate financial integration across African regions and enable smooth cross-currency transactions for trading businesses. However, the real test for the success of the AfCFTA is still pending.

The Covid-19 pandemic has largely disrupted Africa’s development trajectory and the successful start of the AfCFTA. Lockdowns and other containment policies had severe economic impacts. Africa’s GDP dropped by 1.6 per cent in 2020, investment and created jobs shrank by more than 50 per cent, and African exports fell by 5 per cent in February 2020, 16 per cent in March 2020 and 32 per cent in April 2020. This has consequences for the continent’s micro, small and medium-sized enterprises and their ambitions to invest in regional trade. Coming at the time of Africa's recovery struggle, the outbreak of the Ukraine war caused gas prices to rise beyond 100 US dollars (USD), the highest since 2014. These problems are pushing Africa into debt distress and exacerbating the multidimensional poverty and inequality of the region by making food and fuel more expensive, thus constraining indirectly and overall the sustainable development and transformation of Africa.

What benefits to expect from AfCFTA trade liberalisation?

According to the rules of economic theory, the benefits of trade liberalisation are mainly built on the reallocation of production factors (e.g. labour, agricultural inputs) from inefficient to efficient producers. This leads to product specialisation and economies of scale in production. The exposure to regional or international competition for firms results in an adjustment towards optimal firm size and pushes inefficient firms out of the market. In turn, these adjustments create improved access to cheaper products and to more variety. In AfCFTA’s case, this would mean that African consumers and exporting countries benefit at the expense of importing countries. In addition, as an indirect effect, regional integration can stimulate investment in improved technologies, cross-border value chains, R&D and related industries, which then triggers regional production hubs and creates spill-overs along entire value chains. The integration into regional and global value chains opens access to knowledge, capital and improved and efficient inputs, which enable accelerated, across-the-board structural transformation. Industrialisation of value chains creates low- and high-skilled employment opportunities and contributes to income growth.

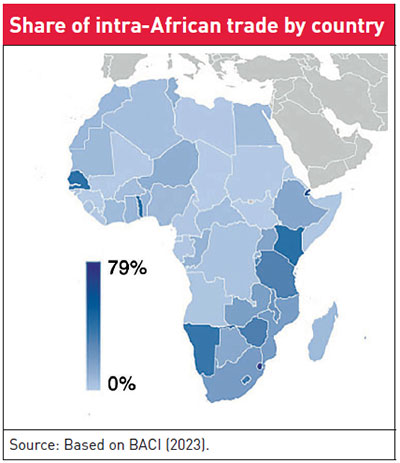

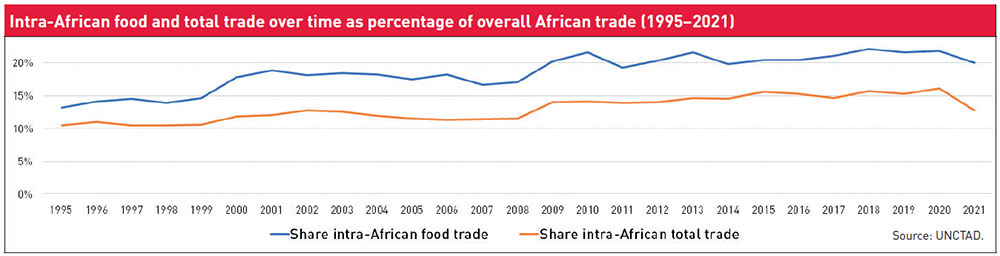

Intra-African trade has accounted for a maximum of 16 per cent of total trade in the past, without accounting for informal trade (see Figure above). Studies by international organisations project that the AfCFTA could boost intra-African trade by between 30 and 80 per cent, leading to economic income gains of about 7 per cent. AfCFTA-related income gains are not distributed equally across sectors and countries, but according to a study by the World Bank, they have the potential to increase income of close to 100 million people and to pull 30 million people in Africa out of extreme poverty by 2035. Intra-African trade liberalisation and increased intra-African trade is expected to go along with sectoral reallocation of labour out of agriculture into the public sector, services and manufacturing. Overall, welfare gains from the agricultural sector are expected to be stronger than from manufacturing owing to moderate demand for intra-Africa trade in manufacturing products and higher existing trade barriers in the agricultural sector. The sectoral gains differ across countries and always benefit those employed in the exporting sector. Manufacturing and service exports from North Africa are expected to increase, resulting in a higher demand for skilled workers in these sectors. This could increase inequality. Overall employment of unskilled labour is projected to increase in the rest of Africa.

The key role of the agricultural sector

The agricultural sector accounts for only 15 per cent of continental GDP, but more than 60 per cent of continental employment, and therefore has a key role in Africa’s economic development. However, intra-African agricultural trade is still as low as 20 per cent of total African trade, although higher than the share of intra-African total trade. The overall African food import bill – the value of food imports from outside of Africa – could increase to 110 billion USD by 2025 without the implementation of the AfCFTA. Currently, the product structure of African exports is not diversified, and is skewed towards unprocessed commodities. Extra-African agricultural exports are mainly unprocessed and largely consist of only few raw commodities (cocoa, coffee, cotton and tea), while extra-African agricultural imports are often processed and higher-value products. These patterns contribute to Africa’s structural food deficit.

Given Africa’s vast agricultural potential related to its favourable climatic conditions, low land prices and a large agricultural labour force, it has long been debated how Africa has only become a food importer since the 1980s. While self-sufficiency in all food commodities is not desirable due to environmental issues and resource availability, Africa’s large structural deficit in staple food production is concerning. According to the UN Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), the level of food import dependency is very different across African economies and different food products within the same country. On average, import dependency is highest among cereal products at more than 40 per cent and animal-based products, such as dairy and meat, at around 20 per cent. Generally, West, Central and North African countries are more import-dependent, particularly regarding cereals and dairy products. Africa’s external import dependency exacerbates vulnerability to global shocks, such as that from the Ukraine war.

However, despite low average agricultural productivity across the continent, the agricultural sector in many African countries has a large export potential. This derives not from a country’s potential per se but from that of individual exporting firms, such that high average competitiveness is not a necessary condition for exports. In line with this consideration, it has been observed that African global competitiveness has increased in recent years and is particularly concentrated in oilseed and legume products. Besides, the intra-African trade of processed products shows a promising upward trend. Hence, trade integration could support greater production of high-value-added products and the emergence of regional agricultural value chains within Africa. The inclusion of the agricultural sector in agrifood chains represents an important opportunity to increase rural income, lower rural poverty and foster pro-poor growth. For instance, food processing plants need several inputs including semi-processed goods like flour.

The AfCFTA, as a continent-wide free trade area, expands tax-free market access for competitive African producers beyond the existing regional economic community (REC) level, which is important given the anticipated rapid growth rates of Africa’s population and food needs. In times of global trade liberalisation and Africa’s enhancing international trade integration, through Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs), the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) and several bilateral trade agreements of African economies with India and China, there is the need to create a level playing field for producers on the continent. While intra-African import tariffs are generally already low, agricultural trade is often more restricted. In addition, non-tariff measures (NTMs) increase the transaction cost of trade, particularly agricultural trade. Despite significant improvements in reducing the costs related to NTMs in agricultural trade, they remain more prevalent than in the manufacturing products trade.

The effects on food security

African food demand is projected to increase by 60 per cent by 2030. The Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP) stipulates higher budget allocations for the agriculture sector and a target of 6 per cent productivity growth. The AfCFTA could potentially reverse this trend by promoting regional integration and trade in agricultural products. Studies predict an increase in intra-African agrifood trade by around 20-30 per cent until 2035. On top of that, extra-African agrifood exports could also increase by about 3.5 per cent. Among the different sectors, gains are expected to be particularly strong for sugar and dairy products.

However, Africa’s food security remains of great concern. More than 20 per cent of Africans are food insecure, and about 40 per cent of their children are stunted. According to the 2022 Global Report on Food Crises, over 140 million people in Africa are in acute food insecurity exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic and the Ukraine war. AfCFTA could have positive effects on the continent’s food security situation in several ways. First, trade integration is projected to improve the accessibility of food by reducing prices and increasing incomes. This could lower the number of food insecure people in Africa by one million, which could be reinforced by long-term indirect effects.

There is also ample evidence suggesting that regional integration in Africa can create economic growth, employment and purchasing power. Second, regional trade integration increases the availability of food. Preferential trade agreements lead to additional trade between the partners of the trade agreement but also reduce the partners’ trade with other countries. In Africa, the experience from past agreements shows consistent overall increases in trade and food availability. Among the RECs, the strongest impact between 1990 and 2012 was found for the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), for which food trade doubled through regional integration. Food trade has not increased through the implementation of ECOWAS, however, the reduction of non-tariff barriers has created production incentives in ECOWAS, leading to higher food supply, thus underlining the importance of trade facilitation. Overall, a country’s food export value is 3 to 5 per cent higher if exporting and importing countries are both in the same REC.

Third, intra-African trade and regional supply chains supported by regional coordination under AfCFTA have the potential to build and meet local demands. Integrated regional value chains, which enhance forward and backward linkages, can reduce Africa’s external dependence and its vulnerability to international shocks, such as the Covid-19 pandemic or the Ukraine war. For instance, intra-African trade can quickly compensate for reduced international imports only if established regional supply chains exist. Our research has shown that production shocks among neighbouring countries are surprisingly uncorrelated in Africa, and therefore can make the grounds for regional trade as a buffer. Hence, regional trade is likely to have positive effects on several food security dimensions.

Notes of caution and prerequisites for the successful implementation of AfCFTA

It has to be borne in mind that the level of existing differences in the level of development, the economic and political fragmentation, regional value chains and comparative advantages among African countries may cause unevenly distributed gains of intra-African trade liberalisation. This calls for economic policies that can compensate the population employed in importing sectors and also for increasing the population’s acceptance of the AfCFTA. According to the 2022 Afrobarometer, trade liberalisation is looked at critically by 40-45 per cent of the African population, while the large majority welcome Pan-Africanism.

However, the expected gains of the AfCFTA are built on clay feet. Most expected gains originate from a reduction in non-tariff measures and not from trade liberalisation. This requires significant investments in national and regional infrastructure and trade facilitation. The harmonisation of quality standards and sanitary and phytosanitary standards is a necessary requirement to facilitate trade. In addition, UNCTAD’s Economic Development in Africa Report 2019 sees the proper set-up of the rules in the original protocol as the game changer for Africa’s industrialisation. All this requires a strong regulatory framework. Currently, the AfCFTA regulations regarding extra-African trade remain vague.

The AfCFTA proposal talks about a free-trade area but not about a common external tariff. Furthermore, only 90 per cent of the total trade shall be liberalised. Without a common external tariff, tariff differentiation could lead to tax competition between governments and open the door for cross-border smuggling between neighbouring countries applying different tax rates. Therefore, regional trade policy without regional coordination of industrial policies could increase protectionism instead of promoting trade integration. An exclusion list, similar to the list of development goods in ECOWAS (see pages 30–31), allows countries to protect local producers of goods which could otherwise be imported from the region. In such a case, the market size argument for small countries disappears. As a consequence of external trade agreements, countries could eventually support and protect producers of the same goods as their trading partners, as the examples of cement and poultry from West Africa show. Therefore, regional industrial policy coordination is required to exploit the benefits of the AfCFTA.

Lukas Kornher is a Senior Researcher at the Center for Development Research (ZEF) at the University of Bonn, Germany, where he coordinates research on markets and trade and impacts on food and nutrition security. His research focuses on global and local food markets, price formation and the role of trade.

Mengistu Wassie works as a Junior Researcher at ZEF and is doing his Doctorate on the impacts of the AfCFTA at the University of Bonn. His research interests primarily focus on development economics and policy, food security, trade, agricultural economics, poverty and economic modelling.

Joachim von Braun is a Distinguished Professor of Economics and Technical Change at ZEF and President of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences. His main areas of expertise include research on development economics and policy, food security, nutrition and health, agricultural economics, natural resources, poverty and science policy.

Contact: lkornher(at)uni-bonn.de

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment