Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Technical know-how is only one side of the coin

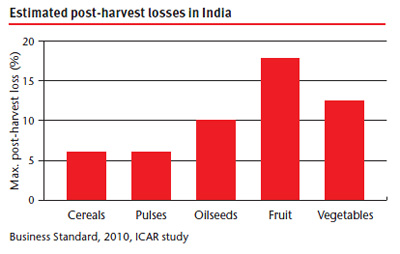

Agricultural produce undergoes a series of operations such as harvesting, threshing, winnowing, bagging, transportation, storage, processing and exchange before it reaches the consumer, and there are appreciable losses in crop output in all these stages. In the tribal, backward areas of West Bengal, Jharkhand, Orissa and Madhya Pradesh, where Welthungerhilfe is focusing its activities, losses are particularly high because the producers here are often unaware of the available best practices and mostly follow age-old traditional techniques learned from their forefathers that are frequently not the most efficient methods. According to a World Bank study (1999), post-harvest losses of food grains in India account for 7–10 per cent of the total production from farm to market level and 4–5 per cent at market and distribution levels. For the system as a whole, such losses have been worked out to be 11–15 million tons of food grains annually, including 3–4 million tons of wheat and 5–7 million tons of rice. Considering an average per capita consumption of about 15 kilograms of food grains per month, these losses would be enough to feed around 70–100 million people, i.e. approximately a third of India’s poor. Post-harvest losses therefore have a significant impact at both the micro and macro levels of the economy. The graph shows an estimate of post-harvest losses across various segments of food assessed by the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR). It demonstrates that post-harvest losses are more significant for fruits and vegetables because of their higher perishability.

According to a World Bank study (1999), post-harvest losses of food grains in India account for 7–10 per cent of the total production from farm to market level and 4–5 per cent at market and distribution levels. For the system as a whole, such losses have been worked out to be 11–15 million tons of food grains annually, including 3–4 million tons of wheat and 5–7 million tons of rice. Considering an average per capita consumption of about 15 kilograms of food grains per month, these losses would be enough to feed around 70–100 million people, i.e. approximately a third of India’s poor. Post-harvest losses therefore have a significant impact at both the micro and macro levels of the economy. The graph shows an estimate of post-harvest losses across various segments of food assessed by the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR). It demonstrates that post-harvest losses are more significant for fruits and vegetables because of their higher perishability.

A structural problem

The agricultural sector in India is highly fragmented when compared to other countries. The average farmer works with just 2–4 acres, and 70 per cent of farmers have less than 2.5 acres (1 hectare). Agriculture and allied sectors contributed to only 14 per cent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2011–12; however, they employed more than 56.6 per cent of the population. Other supply chain actors including transportation companies, traders and whole-sellers are equally fragmented.

As a result, the large agricultural and logistics corporations had less earning opportunities in the respective period, whereas the existing players did not have the scale or capital to make necessary technology and infrastructure investments. The government has therefore been the major player in recent times, creating the infrastructure for storage, transportation, etc. However, the quality of such services has always remained a major concern, and vast areas of the country still do not have adequate facilities because of the unavailability of resources.

At the micro level, small farmers are struggling with their existing knowledge to find solutions to their day-to-day problems of harvesting, processing, storing and, in a very small number of cases, making value additions to the produce before selling it to the market. Here, middlemen grasp the opportunity, and often the rates are hijacked artificially and the producers in need of immediate cash or seeking to avoid rotting of their perishable products have to go for distress selling, losing out heftily on the profit margin.

Government interventions

The Government had taken the initiative of establishing the Food Corporation of India (FCI) in 1965 with the purpose of i) effective price support operations for safeguarding the interests of the farmers, ii) distribution of food grains throughout the country via the Public Distribution System (PDS) and iii) maintaining a satisfactory level of operational and buffer stocks of food grains to ensure national food security. However, the existing infrastructures with FCI fall well short of current requirements. The media reports have exposed huge amounts of food rotting at the FCI go-downs. An esteemed daily newspaper in India, the Hindustan Times, reported on July 27, 2010 that about 10,688 lakh (1,068 million tons) of food grains were found damaged in FCI depots, enough to feed over six hundred thousand people for over ten years. On the other hand, the Targeted PDS, which has the mandate to provide food grains to the vulnerable and marginalised poor, is suffering from a shortage of supply, and most of the consumers are complaining about corruption at the PDS outlets stopping them to receive food to meet their hunger. Once passed, the National Food Security Act may alleviate the problem as the government will have to distribute 62 tons of food grains annually, which will in turn reduce pressure on the FCI stores.

Capacity building at all levels

The Welthungerhilfe projects are targeting various points along the value chain. Under the project Vocational education and training, the rural youth from the most backward areas of West Bengal, Jharkhand and Orissa have been trained on sustainable harvesting and processing techniques, which has reduced their losses significantly. The training on Food processing and value addition has helped the farmers to process fruits and vegetables as different food items and sell them to the market. Altogether, 450 farmers have been trained on sustainable agriculture practices (including post-harvest management), and another 50 farmers on food processing and value addition.

Under the Market access project in Jharkhand, with its partner Centre for World Solidarity, Welthungerhilfe worked on the entire value chain of paddy with more than 300 farmers following Systems of Rice Intensification techniques (see also Rural 21, 4/2012), which helped the small producers to almost double the traditional yield of 30 quintal/ha (1 quintal = 100 kg). The training also helped the farmers to realise the problems of the traditional practices of processing paddy and take a more scientific approach. Common Facility Centres extended mechanisation support to the marginalised farmers by introducing paddy threshers; local youths were encouraged to initiate mobile milling machines on tractors. As a result the farmers were able to properly mill their paddy to rice. Three women’s self-help groups learned the processes of making puffed rice out of paddy and are now able to directly package and market it. The local value addition of rice is ensuring a better economic return of the produce.

After taking a training on Spice grinding and processing, the tribal rural women of Kashipur initiated a small turmeric processing plant very recently and started selling turmeric packets that they produced in their own fields. In the past, they would sell the produce to the middleman at a much cheaper rate. But now, after processing, they are able to receive a rate of around 120 rupees (INR) per kilogram, compared to the earlier rate of INR 80/kg.

Giving communities a stronger voice

Currently, the communities are very enthusiastic about post-harvest processing and value addition to reduce losses and increase income. The smaller farmers have been collectivised into farmer clubs, self-help groups enabling them to participate in learning, share their experiences and collectively process and market their produce to reduce loss. The villagers are also taking collective efforts to market the fresh vegetables directly by negotiating with the traders on collective terms to guarantee timely procurement and better rates. The involvement of the self-help groups also ensures women’s participation and sharing of responsibilities. Welthungerhilfe, under the Fight Hunger First Initiative, is also advocating for a better and more accountable PDS, whereas the communities in Jharkhand, West Bengal, Orissa and Madhyapradesh are addressing Community Monitoring of Public Services with tools such as Social Audit, Community Score Card etc.

The biggest challenge in India is to attain fairer and more transparent public distribution that can really reach the poor in time. Therefore, alongside imparting technical know-how on post-harvest management and setting up primary infrastructure for storage and distribution, the communities have to claim their right to food and put pressure on the PDS to improve its services.

Subhankar Chatterjee

Programme Manager - Welthungerhilfe Kolkata

Kolkata, India

subhankar.chatterjee@welthungerhilfe.de

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment