Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Gender justice – a precondition for resilience

The world has witnessed a series of compounding, overlapping and, in some cases, reoccurring shocks and stressors in recent years, including the Covid-19 pandemic, the global food crisis triggered by Russia’s war on Ukraine, several localised conflicts around the globe and the intensifying climate crisis. Thus, policies, investments and interventions focused on increasing resilience have become essential to help vulnerable populations rebound from these disturbances, while becoming better prepared to handle inevitable future shocks and stressors.

Resilience

Resilience is a complex concept that is understood and utilised in different ways by different disciplines. We adopt the definition by USAID which describes resilience as “the ability of people, households, communities, countries, and systems to mitigate, adapt to, and recover from shocks and stresses in a manner that reduces chronic vulnerability and facilitates inclusive growth” (USAID, 2012, p. 5). Thus, building resilience requires investments and interventions that build adaptive capacities, such as expanding economic opportunities, education, and nutrition and health services, while also identifying and reducing context-specific risks.

Whereas these multiple crises affect many vulnerable communities in low- and middle-income countries, there are particular gender-differentiated impacts which present unique challenges to the well-being of women and girls. Careful consideration of these gender-differentiated impacts is required for policy and programme responses to meet the needs of women and girls, tackle long-standing gender inequalities and promote sustainable pathways to recovery. Without a gender lens, the proposed measures will fail to meet the specific needs of women and girls and may even exacerbate gender inequalities.

The UN Food and Agriculture Organization (2023) report The Status of Women in Agrifood Systems shows that as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic and the related economic crisis, 22 per cent of women lost their jobs in off-farm agri-food systems work in the first year of the pandemic, compared to only 2 per cent of men. Furthermore, the gap in food insecurity between men and women widened from 1.7 percentage points in 2019 to 4.3 percentage points in 2021. These gender gaps are driven by underlying gender inequalities in agri-food systems, such as the fact that women’s livelihoods and working conditions are marginalised, informal, irregular and low-skilled and thus more vulnerable to shocks than men’s. Moreover, girls and young women face particular risks when confronted with shocks and stressors, such as a higher likelihood of being withdrawn from school, gender-based violence and economic or sexual exploitation.

Vulnerability and resilience also depend on other intersectional identities, such as age, marital status, class and ethnicity. For instance, women heads of household may face greater limitations in access to land, capital, social networks and labour, while married women may benefit from access to these resources through male household members but have less decision-making authority or autonomy. Similarly, women in different food environments (such as rural or urban contexts) may face different challenges. For example, while women in rural farming communities may experience adverse impacts of droughts on their water security and livelihoods, women in urban contexts may face greater challenges related to flooding and associated health risks, like cholera, given poor water infrastructure and crowded conditions.

In times of crisis, girls have a higher likelihood of being withdrawn from school than boys. Photo: Jörg Böthling

Towards gender-transformative change

So what can be done to support the capacity of women and girls to respond more effectively to disturbances and contribute to the resilience of their households and communities while addressing underlying gender inequalities that make women and girls more vulnerable in the first place? One useful framework for thinking about the approaches needed to achieve gender equality and resilience goals is the Reach-Benefit-Empower-Transform Framework.

There is growing recognition among development practitioners, researchers and policy-makers that simply reaching women (e.g. including women in programme activities) is not enough to address gender inequalities. Policies, interventions and investments must ensure that women benefit from these interventions through measured improvements in their well-being (e.g. food security, income and health). This means ensuring that women have access to information and finance needed to increase productivity on the plots they manage, take advantage of economic opportunities and grow their enterprises. It means expanding social protection and violence prevention programmes to women in rural areas and providing other incentives to keep girls in school.

Increasingly, interventions aim to facilitate women’s empowerment by providing them with more opportunities to make decisions and realise their own goals. Women’s groups and networks often represent an important source of resilience as well as a platform for women’s empowerment by offering opportunities to share labour, childcare responsibilities, access to savings, credit and government services, the ability to access and build assets, and increased political engagement.

However, even efforts to increase women’s agency may not be enough to reduce gender inequalities in agri-food systems and increase women’s resilience. Gender-transformative approaches (GTAs) may be required for deeper and more lasting improvements in the status of women. Gender-transformative change goes beyond the individual and household levels to remove structural barriers in society. Thus, GTAs require multi-pronged, multi-scale approaches that involve challenging patriarchal norms which underpin harmful cultural beliefs and attitudes, gender inequalities in institutions, policy frameworks and governing structures at multiple scales, and gendered power dynamics and relations. They also depend on engaging men and boys as partners for gender equality.

Group-based approaches are promising

One example of a project that incorporated gender-transformative approaches is the “Joint Programme on Accelerating Progress towards the Empowerment of Rural Women (JP RWEE)” led by numerous UN agencies and implemented across several countries including Ethiopia, Kyrgyzstan, Nepal and Niger. JP RWEE activities for transforming gender relations included dialogues at the household and community levels to promote more inclusive decision-making processes and engaging men and boys as champions for gender equality.

Among these approaches are IFAD’s Gender Action Learning System (GALS) intervention and FAO’s Dimitra Clubs, which bring men and women together at the household and community levels to listen to each other and work together to solve local challenges. These dialogues also provide a platform for trained facilitators to raise awareness of harmful gender norms, attitudes and beliefs, and to challenge unequal structures (such as local rules governing resource access). Importantly, JP RWEE relied on group-based platforms or approaches aiming to expand economic and livelihood opportunities for women and/or increase their access to resources like microcredit or savings.

Research shows that the group-based approaches were core to the successes of the project, which included increasing women’s involvement in livelihood decisions, asset ownership, credit decisions and, in some cases, income decisions. Having men take part in the interventions was also crucial to avoid potential backlash from the activities focused on women’s groups and to promote changes in gender relations and norms.

While there is limited evidence of the effectiveness of applying gender-transformative approaches as part of resilience-building interventions, clearly, the status quo is not working. Intentional efforts and commitments from the development community to tackle persistent gender inequality is essential to ensure that women from all walks of life are actively engaged in efforts to restore their economies and communities. Achieving this transformation will require interventions that prioritise gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls, instead of pivoting from it. Women-led and women’s rights organisations must take centre stage in designing and implementing interventions and have their voices heard in national and international platforms. A strong focus on justice, equality, inclusiveness and human rights must be at the heart of every effort to build resilient agri-food systems and rural livelihoods. Despite the many challenges that women and girls are facing, they remain essential to the success of any crisis response.

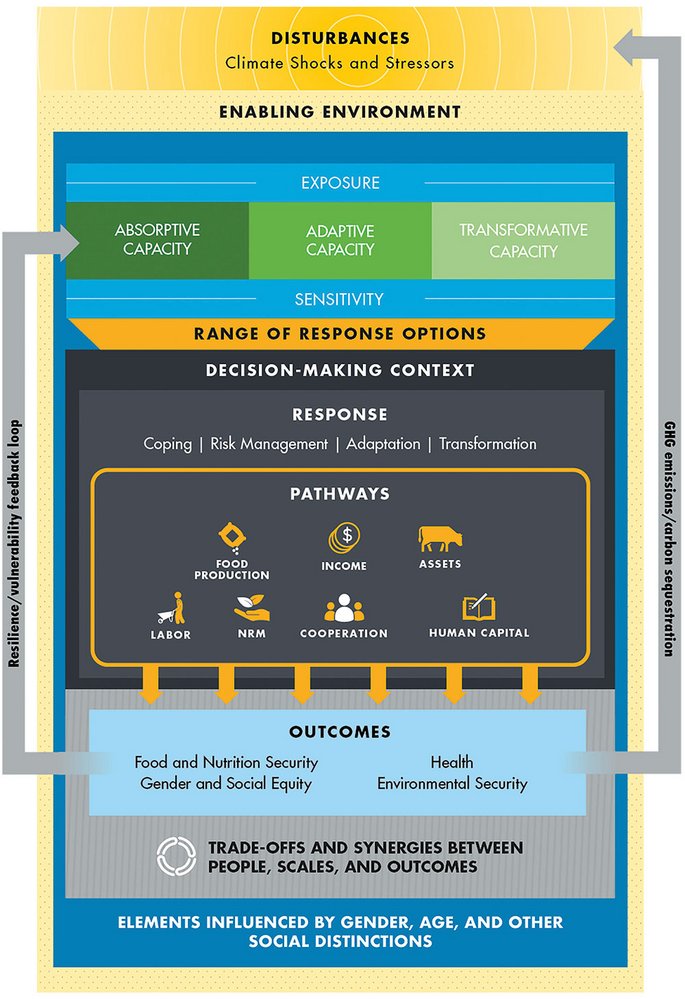

Conceptual linkages between gender, resilience and food security

IFPRI’s Gender, Climate Change, and Nutrition Integration Initiative (GCAN) uses a conceptual framework to illustrate the gender dimensions of resilience (see Figure). Each of the components in this framework is shaped by gender differences. Men and women have different levels of exposure and sensitivity to various shocks and stressors, driven by gender differences in livelihood roles, health and nutrition status, and other contextual factors.

For example, men are more likely to migrate away from climate-stressed areas while women remain behind, leaving them more highly exposed to climate stress. Similarly, women tend to have lower resilience capacities to respond to disturbances given less access to information, finance and other services, more limited access to and control over assets, more restrictive social norms and a generally higher work burden compared to men, among other factors. Women’s generally lower resilience capacities limit their ability to respond to the shocks and stressors that they face, including the options available to them. For example, women’s poorer access to information and extension services limits their adoption of climate-smart practices that relate to their livelihood roles and their ability to maintain or increase agricultural productivity during times of crisis, such as the Covid-19 pandemic or after a flood event.

When women are empowered to make decisions in agri-food systems, this can increase their contribution to resilience. In Bangladesh, women’s involvement in agricultural decisions increases the production diversification away from rice towards other crop types, with positive implications for climate resilience (by reducing risks associated with monocropping of rice) and nutrition (through diversified diets). Ultimately, the choices that are made in response to shocks and stresses have different implications for men’s and women’s well-being outcomes. For instance, the combination of climate stressors and the introduction of new climate-smart technologies or practices can influence the allocation of household labour in ways that exacerbate women’s work burden in agriculture. Recent studies show that women’s labour intensity in agriculture is increasing relative to men’s under heat stress, likely given men’s easier access to alternative livelihoods.

Elizabeth Bryan is a Senior Scientist in the Natural Resources and Resilience Unit at the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) in Washington, DC, USA, where she conducts policy-relevant research on gender, sustainable agricultural production, climate-smart agriculture and small-scale irrigation, using mixed methods. Elizabeth currently leads the Gender, Climate Change, and Nutrition Integration Initiative (GCAN).

Ruth Meinzen-Dick is a Senior Research Fellow in the Natural Resources and Resilience Unit at IFPRI, where her work focuses on two broad (and sometimes interrelated) areas: how institutions affect how people manage natural resources and the role of gender in development processes. Ruth is a co-creator of the Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index (WEAI) and recipient of the Elinor Ostrom Collective Governance of the Commons 2019 Senior Scholar Award.

Claudia Ringler is Director of the Natural Resource and Resilience Unit at IFPRI, where she coordinates research at the intersection of nature, agriculture and development for tangible progress toward more equitable and resilient food systems. As co-lead of the CGIAR NEXUS Gains initiative, she drives research on the role of energy in transforming food and water systems, and on climate change adaptation, mitigation as well as water and other natural resource interventions for increased equity and resilience.

Contact: e.bryan@cgiar.org

References:

Alvi, M., P. Barooah, S. Gupta, and S. Saini. 2021. Women's access to agriculture extension amidst COVID-19: Insights from Gujarat, India and Dang, Nepal. Agricultural Systems, 188: 103035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2020.103035.

Azzarri, C. and G. Nico. 2022. Sex-Disaggregated Agricultural Extension and Weather Variability in Africa South of the Sahara.” World Development, 155: 105897. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2022.105897.

Bryan, E., C. Ringler, and R. Meinzen-Dick. 2023. Gender, Resilience, and Food Systems. In Resilience and Food Security in a Food Systems Context, C. Béné and S. Devereux (Eds), 239-280, Palgrave-MacMillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-23535-1_8

Bryan, E., M. Alvi, S. Huyer, and C. Ringler. 2023. Addressing gender inequalities and strengthening women’s agency for climate-resilient and sustainable food systems. Background paper for Report on The Status of Rural Women in Agri-food Systems: 10 Years after the SOFA 2010-11 of FAO. Nairobi, Kenya: CGIAR GENDER Platform, https://cgspace.cgiar.org/handle/10568/129709.

Bryan, E., E. Kato, and Q. Bernier. 2021. Gender differences in awareness and adoption of climate-smart agriculture practices in Bangladesh. In Gender, Climate Change and Livelihoods: Vulnerabilities and Adaptations, J. Eastin and K. Dupuy (Eds.), Wallingford, UK:

CABI. Available at: https://www.cabi.org/bookshop/book/9781789247077/

De Pinto, A., G. Seymour, E. Bryan, and P. Bhandari. 2020. Women’s empowerment and farmland allocations in Bangladesh: evidence of a possible pathway to crop diversification. Climatic Change, 163: 1025–1043. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-020-02925-w.

FAO. 2023. The Status of Women in Agrifood Systems. Rome. https://doi.org/10.4060/cc5343en

Lee, Y., B. Haile, G. Seymour, and C. Azzarri. 2021. The Heat Never Bothered Me Anyway: Gender-Specific Response of Agricultural Labor to Climatic Shocks in Tanzania. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 43 (2): 732–49. doi.org/10.1002/aepp.13153.

Nico, G. and C. Azzarri. 2022. Weather Variability and Extreme Shocks in Africa. IFPRI Discussion Paper, 2115. Washington, DC: IFPRI.

Quisumbing, A., B. Gerli, S Faas, J. Heckert, H. Malapit, C. McCarron, R. Meinzen-Dick, and F. Paz. 2023. Assessing multicountry programs through a “Reach, Benefit, Empower, Transform” lens. Global Food Security 37(June 2023): 100675. doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2023.100685

Add a comment

Comments :