Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Community banks: A chance for agri-based African rural communities

Community banking can be defined as a process where ten or more people come together to form savings and borrowing self-help groups (SHG) geared towards increasing access to credit for joint venture enterprises formation. Community banks thrive on a group spirit, giving each member responsibility. Unlike the commercial banks, lending and borrowing decisions here are made based on the SHG members’ understanding of their local needs, their families, businesses and socio-economic contexts.

Currently, there is a huge gap between communities and commercial banks. The latter are usually hesitant to lend money to small farmers due to the unpredictability of the agricultural sector. Where loans are secured, the interest rates are too high for smallholders to hit their targets. However, the authors are not making a faraway call to boycott commercial banking services: in fact, the reverse is true. The aim is to suggest a financial model based on the cultural context of rural communities, which could motivate commercial banks leveraging the economic capacities of rural communities.

An African tradition …

Community banking under SHGs has been part and parcel of African social structures and belief systems, although its potential to generate considerable economic development has so far been disregarded by development planners and policy-makers. Most development models have not taken into account challenges that afflict African rural communities, including the misdistribution of income and property. There still exist stereotypes like that Africans lack a saving culture. Before the Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) was started in 1987/88, agricultural growth and development had been predominated by farmers’ cooperative unions. Their collapse in the 1980s and new, institutional economic policy thinking in the context of SAP, which entailed a liberalisation of the financial sector, have not significantly transformed thinking within commercial banks. Their promotion strategies have persistently remained weak, and very little has been done in enabling a supportive environment for smallholder farmers. Ironically, emphasis has always been placed on collateral security, while institutional factors like the social capital of the SHGs have been neglected.

… with its own rules

In contrast with the old believe and stereotypes, Africans will maintain a saving culture if they are organised in self-help groups. However, this saving culture has taken on traditional ways and forms differing from those of the western commercial model. In South Western Uganda, where the Open Distance Learning Network (ODLN) team has concentrated its activities, cases of an evolutionary saving culture for some women farmers and their groups are indeed interesting, progressing for example from chickens to goats and then cows (the “livestock ladder”). There is also a clear evolutionary pattern of SHGs growing from tackling emergencies (e.g. burial and sickness costs) on to meeting social needs (e.g. introductions and weddings) and to what is now savings and borrowing for commercial investments.

How can SHGs evolve into community banks?

The process of a SHG to evolve into a community bank is chiefly determined by three stages. In the first stage, group formation is mainly emergency-driven, i.e. burials, droughts, and epidemic outbreaks, among other social problems. In case of social events, members contribute and offer support for each other on occasions like new harvests, weddings or the birth of twins, among other social obligations.

In the second stage, members realise the need to develop their households jointly. This can take different forms but mainly, emphasis is on non-performing assets like savings for material support in form of furniture, contributions to buy iron sheets, house utensils and other domestic needs. At this stage, members can opt to start lending small loans to members specifically for joint or individual enterprises at a small interest fee.

The third stage is the most important one. Here, the members realise the need to vigorously save and borrow in order to expand their businesses. However, their capacity is always hindered by financial capital. Here, members realise the need to outsource for additional funding, especially from a commercial bank. At this stage, they may have a prior experience with a commercial bank, either positive or negative, but a high level of empowerment and engagement is realised. Members can also set bylaws for attendance, penalties, governance, interest rates, loan repayment either weekly or monthly and shareholding, among other issues. At this stage, a high level of engagement is necessary. This can be in form of organisational development, negotiating skills, conflict resolution, the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with stakeholders like traders or input dealers, regular access to information and better book-keeping skills.

A typical example of a community bank in Uganda

Sarome Kantaki is a 75-year-old founder of Mumpalo Ngozi SHG in South Western Uganda. She started the group as a burial group in 1996, together with other two colleagues. Fifteen years down the road, the group is now a saving group benefiting up to 30 women and 30 men with a net working capital valued at 10 million Ugandan shillings, equivalent to 4,000 USD. The SHG has currently applied for a loan worth 3,200 USD to invest in a boat engine in order to readily access markets in towns like Kabale, as well as for tourists visiting Lake Bunyonyi.

Today, major innovations/achievements in the community banking model involve the integration of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) like mobile money for savings and borrowing and issuing of financial statements to members. One of the community banks in Uganda has hired a financial consultant to advise the members on commercial investment opportunities for their accumulated profits.

In India, the Indian Overseas Bank, one of the major public sector banks, has offered loans to 320 women community banks to the tune of 112,000,000 Rupees (approximately 270,000 US dollars). This example shows how community banks could bridge the gap and make the community move closer to the commercial banks.

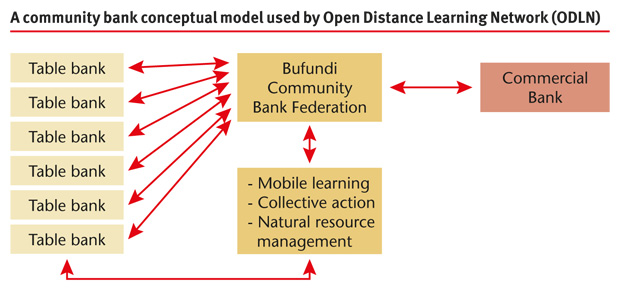

Currently, the Open Distance Learning Network (ODLN) has mobilised and strengthened 40 SHGs comprising up to 1,000 farmers through local savings and credit as a form of building social, human, financial and physical capital. The model mainly supports potato and honey value chains where farmer enterprise groups are assisted in collectively managing their natural resources, purchasing clean potato seeds, value addition, savings and borrowing as well as collective trading in marketable crops like beans and sorghum. The community bank model that is used by ODLN is presented below.

SHGs have also been empowered in business proposal formation, organisational development, negotiating skills, with MoUs signed, constitutions and formulating bylaws as well as the exploration of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) like mobile learning through their mobile phones. A series of field visits and capacity building training workshops have also been conducted.

Key lessons from community banks

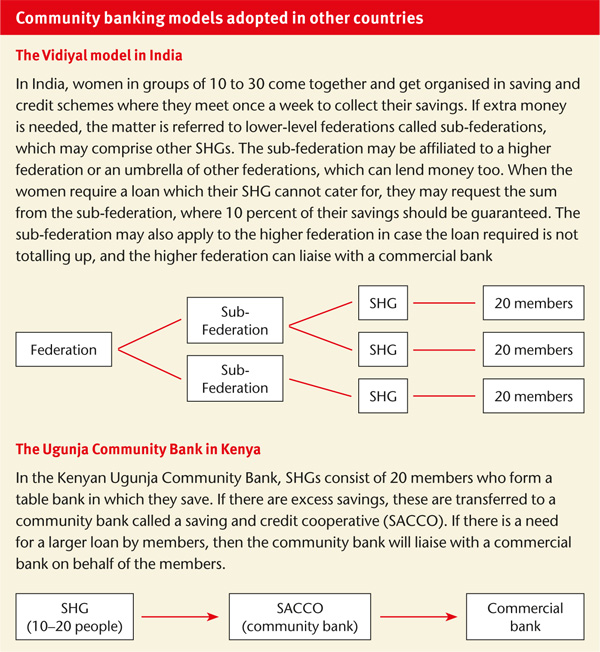

The model of community banks is not new. A number of approaches have been adopted from different countries, such as India (Vidiyal model) and Kenya (Ugunja model in the country’s West; see Box at the end of the article). Some common aspects and recommendations can be derived from experience gathered:

- If rural credit is blended with appropriate capacity building, the performance of rural credit will be much better vis-à-vis productivity, returns and non-performing asset (NPA) levels.

- Capacity building of community banks can enlarge the market for commercial bank credit among small and marginal rural poor.

- The modern information and communication technologies through structures such as rural Internet kiosks, rural telecentres, mobile phones and community radios can facilitate the capacity building processes in a spatial and temporal context which is financially viable, economically feasible and socially acceptable.

- SHGs are formed on the basis of kinship and neighbourhood. Thus a strong sense of belonging, joint liability and participatory decision-making processes characterise the groups.

However, creating an appropriate model for a particular country does not necessarily mean adopting the existing model working in one country or community as there will be individual environmental needs and constraints.

Community banks are envisaged to bridge the huge gap between communities and commercial banks. However, this is only possible through tapping into the indigenous saving schemes which have existed with farmers for a long time, rather than imposing new ones on them.

More information: www.l3fuganda.mak.ac.ug

Authors: Robert Kaliisa

robertkaliisa@yahoo.com

Zizinga Alex, Kodhandaraman

Balasubramanian, Ronald Kasule, James Lukenge, Moses Tenywa

Open Distance Learning Network (ODLN)

Agricultural Research Institute Kabanyolo

Makerere University - Kampala, Uganda

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment