Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Better coordination through contract farming

At the heart of contract farming (CF) is an agreement between farmers and buyers in which both parties agree in advance on the terms and conditions for the production and marketing of farm products, usually including the price to be paid, quantity and quality demanded and delivery dates. The contract may also include information on how the production will be carried out or if any inputs such as seeds and fertilisers, financial assistance and technical advice will be provided by the buyer.

CF has been developed and practised for decades. The more recent growth of CF particularly in developing countries is largely linked to transformations of agrifood systems with increasing demands and requirements for agricultural products, growing competition in agrifood markets and rising dominance of global value chains. CF can allow more efficient and integrated vertical and horizontal coordination of value chains and input and output markets.

Beyond efficiency

It also provides a way for buyers to work more closely with partners in sourcing agricultural products as more consumers demand products that are not only safe to consume but also are of higher quality and greater variety, and are produced in ways that do not damage the environment or harm the workers. The growing interest in CF can hence be attributed not only to efficiency in order to respond to the transformations caused by globalisation processes, but also to an increasing focus on other dimensions of sustainable growth such as economic and social inclusion and environmental responsibility. Smallholder farmers often face various barriers to participating in modern markets, such as lack of access to input and output markets, technologies, and financial and other support services. They are also confronted with challenges of increasing and changing demand, rapid technology advancement and accelerating impact of climate change and natural resource scarcity. CF can help relieve some of these constraints and challenges for smallholders. As poverty is more prevalent in rural areas and at the same time smallholder farming is central to food security, CF schemes have increasingly been seen as a key mechanism to address these issues as opposed to traditional open-market procurement systems. CF has the potential to promote inclusive and sustainable growth through providing access to resources, technologies and economic opportunities to smallholders as well as through incorporating environmental and social measures in its operations.

Advantages and disadvantages of contract farming

Engaging in CF can have both pros and cons for the actors involved. For farmers, CF can help overcome some constraints and obstacles to market participation, as discussed above. CF connects farmers to buyers and markets. It is possible for farmers to know in advance when, to whom, how many and at what price, and hence this may reduce risks, secure more stable income for farmers and allow them to manage risk and plan better. Many CF schemes introduce new or improved technologies such as new seeds and production methods and provide technical support and training to farmers. CF can also ease farmers’ access to inputs and support services such as quality control, transportation and storage that can be part of contractual agreements. For example, fertiliser can be supplied on credit through advance from the company. All these advantages and the development of human capital through experiential learning in producing and marketing one’s products can result in more resilient and sustained growth in productivity, competitiveness, income and ability to cope new challenges, which can lead to improved food security and nutrition and better health, education and wellness outcomes.

| Advantages for farmers | Advantages for buyers |

|---|---|

| Easier access to markets, inputs, technologies, training, credits, services, etc. | More consistent supply and quality |

| Gains in knowledge, skills, experiences and human capital | Increased efficiency |

| Increased productivity | Lower risks and better risk management |

More secure market More stable income | Products conform to standards on quality, safety, social and environmental responsibility |

| Disadvantages for farmers | Disadvantages for buyers |

| Loss of flexibility to sell to other buyers for higher prices | Reduced supply options |

| Lack of bargaining power | High transaction costs of contracting with many small farmers |

| Possible delays in payments and input delivery | Risks of farmers breaking contracts and side-selling |

| Possible indebtedness | Potential misuse of inputs, non-compliance of process or standards |

| Environmental risks of growing only one or certain type of crop | Reputation risks if things go wrong |

The major advantages of CF for buyers include more reliable and efficient supply of raw materials and more consistent quality in comparison to the open market. This is in part because CF arrangements allow the companies to introduce production requirements and quality and other standards and to monitor the process as they have closer relations with farmers compared to open-market procurements. The sponsoring companies may have lower risks and manage risks better as they are more informed of the production process. Cooperating with many small farmers can also help overcome land constraints companies might be facing. Integrated provisions of inputs and support services and a more streamlined supply chain can result in gains in efficiency and competitiveness. Furthermore, CF makes it possible for companies to incorporate standards on social and environmental responsibility and improve due diligence in supply chain management.

Farmers, however, can face serious problems in CF schemes, such as unequal bargaining powers between farmers and companies, inefficiencies in management and delays in the delivery of inputs or payments. They also risk indebtedness because of these difficulties or excessive loans from the buyer. This can result in increased dependency on the buyer which can increase the risk of being exploited. Moreover, farmers under a CF agreement usually are not permitted to sell to other buyers when prices rise, which limits their selling options. Buyers might also be facing certain disadvantages. Likewise, companies may have less flexibility in sourcing supplies as they have committed resources to CF and are bound by the contract. While trust is a central factor in such agreements, farmers may break the contract and side-sell their product to other buyers. It can also happen that farmers misuse inputs supplied on credit or do not comply with agreed terms on quantity, quality, delivery or production processes. This can negatively impact yields, supply and quality. The increase in CF occurring around the world seems to indicate that the positive aspects tend to outweigh the negative ones. Nonetheless, CF may not be the only or suitable way to organise a commercial relationship, and a good analysis of pros, cons and its alternatives should be considered.

Contract farming and the law

For CF to truly thrive, it requires an enabling legal and regulatory framework at national level. This broad system of laws and regulations governs CF and can help maximise the benefits and minimise the risks of CF. When set up appropriately, this framework can help recognise and protect people’s rights and balance the contractual power of involved parties, provide legal security to contractual relations and facilitate enforcement. Overall, it can contribute to enhancing trust between parties in CF, when they know that their rights are both protected and enforceable. The appropriate CF regulatory framework can take many different forms, none of which is necessarily superior to the others. It depends on the country context, its policy needs as well as its legal tradition. Rules related to CF can be placed in specific CF laws, general agriculture legislation, general contract law (including civil codes) or commodity-based legislation among other approaches.

It is useful for legislation to include a reference to the minimum content or provisions that a contract should incorporate to be considered as a complete agricultural production contract. As identified by the Legal Guide on CF and illustrated in the Model Agreement for Responsible CF (see Boxes), these provisions include the parties to the contract, technical specifications (e.g. quality and quantity requirements), input supply, price determination and payment, delivery, applicable law and dispute resolution. The parties would always include the producer and the buyer, either as individuals or as legal persons such as producer organisations or corporations, and may include third parties, such as input or finance providers. Technical specifications form the core of the agreement and allow buyers to specify the exact quality and quantity of their product and more effectively organise their supply stream. Dispute resolution through alternative dispute resolution (ADR) mechanisms often offers more suitable and effectual solutions than the use of courts as ADR tends to be faster, simpler and less expensive and thus can better support the parties’ access to justice. The substantive elements may also include regulatory mechanisms to support, encourage or maintain regulatory control over CF operations. Further, it should always be required that agreements be made in writing. Beyond the legislation that directly affects the parties’ relationships, there is a vast field of other laws and regulations that can influence CF. Competition and labour laws may be applicable to the contract and prevent the use of certain unfair contract terms and abusive practices. Input legislation such as for seeds, fertilisers or pesticides can place limits on input usages. Intellectual property legislation may offer protections and place limitations on farmers’ use of some inputs or technologies after the contractual relationship ends. Quality standards can guide the quality requirements as agreed in the contract, and environmental rules must always be followed and cannot be contracted away. This brief listing is by no means comprehensive, and any individual country would most probably have many other laws and regulations which would impact CF participation and operation.

Carmen Bullon and Teemu Viinikainen are workingin the Legal Office and Lan Li, Costanza Rizzo and Jodean Remengesau are from the Agricultural Development Economics Division, all at FAO headquarters in Rome, Italy.

Contact: contract-farming@fao.org

Further reading:

Website of the FAO Contract Farming Resource Centre

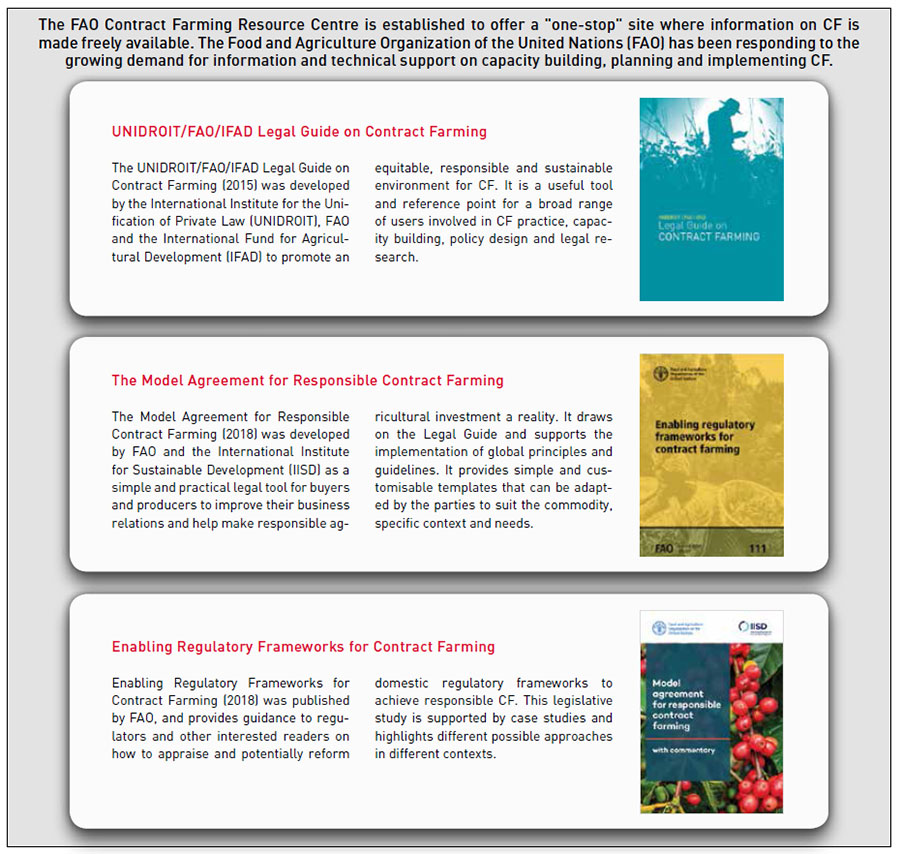

FAO (2018). Enabling Regulatory Frameworks for Contract Farming. Rome, FAO.

FAO and IISD (2018). Model Agreement for Responsible Contract Farming with commentary. Rome, FAO.

UNIDROIT, FAO and IFAD (2015). UNIDROIT/FAO/IFAD Legal Guide on Contract Farming. Rome, FAO.

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment