Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Livelihoods beyond survival

Ensuring resilient livelihoods and sustained employment for vulnerable communities was already a stretch in normal (pre-COVID-19) times, but we have now entered a new reality. For most of us, this situation has largely meant a change in the way we work and live, an inconvenience at most but still largely manageable. However, for vulnerable communities that lack a stable income, the impact is significantly different. With border closures and travel restrictions in place, the subsequent downturn in trade has massively affected income and employment of vulnerable communities, particularly those that are self-employed. These self-employed people also include small-scale farmers. Currently, more than 475 million smallholder families work on less than two hectares of land. In addition, average equilibrium market wages can be low, with prices that farmers earn for agricultural produce economically unsustainable.

It is a fundamental human right to be able to earn enough for a decent life. But for far too many people, particularly farming families in the Global South, their income barely covers the cost of living. Families struggle to afford the food and healthcare they need or to send their children to school. Even for those who are getting by, a bad harvest, an accident or some other unexpected event – like the one we are experiencing now – is all it takes to tip them back into poverty.

It does not have to be this way. When farming households earn enough to live on, it is more than their own quality of life that improves. They can afford to reinvest in their farms, buy equipment and new seeds, and raise the quality and diversity of the crops they produce. Yields and profits increase. Families can set something aside to see them through difficult times. Women set up new businesses. Children no longer have to toil in the fields, and their parents can pay school fees and buy uniforms. The vicious cycle of poverty becomes a virtuous circle.

Living income – directly linked to the SDGs

The concept of living income clearly has implications for sustainable development and links directly to a number of the UN's Sustainable Development Goals (SGDs), in particular, SDGs 1 (no poverty), 2 (zero hunger), 8 (decent work and economic growth), 10 (reduced inequalities) and 17 (partnerships for the goals). This is not to say that these are the only associated goals. In fact, organisations such as the Sustainable Food Lab and Business Fights Poverty have identified levers for improving smallholder incomes that strongly associate with several other SDGs.

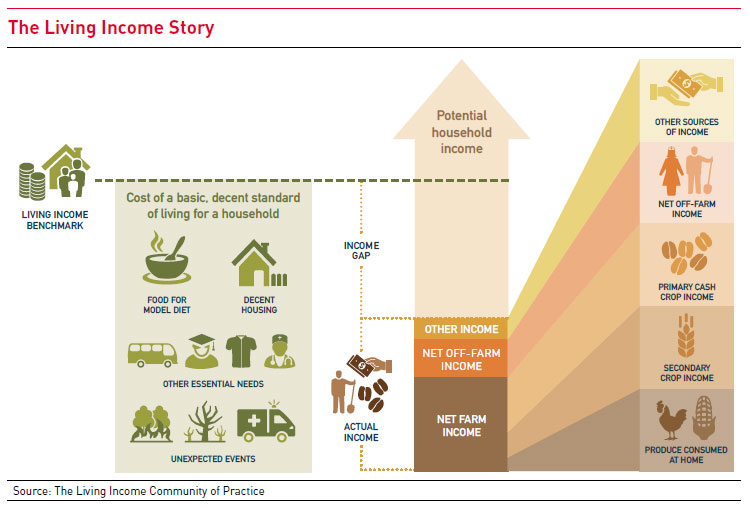

An increasing number of organisations have begun focusing on the concept of a living income – defined as the net annual income required for a household in a particular place to afford a decent standard of living for all members of that household. This includes food, water, housing, education, healthcare, transport, clothing and other essential needs, including provision for unexpected events.

The concept of living income builds on the work of the Global Living Wage Coalition, which publishes living wage levels for different countries based on a shared definition and methodology. While a living wage applies to hired workers in farms, factories and other enterprises, a living income also encompasses the hundreds of millions of smallholders and farmers who are self-employed and can be more complex to address. These households may earn income from multiple sources, including off-farm labour and other businesses as well as a variety of crops. To understand and address this complexity, a multi-stakeholder approach is needed.

Chances and challenges

Of course, efforts to reduce poverty and improve conditions for smallholders are hardly new. But the idea of a living income is about more than just basic subsistence and survival: it is about dignity, stability and resilience. And it leads to lasting change. Because so many of these smallholders are linked to global agricultural and commodity supply chains, it is a shared responsibility.

The business benefits of assuming such responsibility and investing in smallholder supply chains are also evident. They can include long-term supply security, improved quality and yields, greater supply chain transparency and new market creation. Supporting smallholders can also build stronger government relationships, increase the ability to meet stakeholder expectations, enhance reputation and align with initiatives such as the SDGs. In some cases, investing in local supply chains reduces costs and minimises price volatility and currency risks.

While tackling poverty may seem impossibly broad, a living income provides a clear, measurable and consistent view. By looking at what constitutes a living income for smallholders in a region and what they earn today, it’s possible to get a clearer idea of what action needs to be taken to close that gap and subsequently move beyond.

Effective strategies to close the income gap

There are various levers in place to help drive change and close the income gap, such as:

- implementing sustainable programmes at the producer level

- applying a smart mix of solutions to balance supply and demand

- embedding sustainability systems and strategies to specifically address living income.

In addition to this, subsequent monitoring and reporting on improved outcomes is equally important. In this respect, sustainability standards play a significant role in implementing activities and functions to help bring about specific short- and medium-term changes, which help achieve long-term goals. We see examples of these in the Fairtrade living income strategy, which comprises a holistic approach to address income as a specific topic, and the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil’s smallholder strategy, which not only stresses the importance of smallholder inclusion in sustainability programmes, but also places livelihood improvement as a key objective.

In addition to these efforts already in place, more needs to be done to better address the biggest challenges faced by all (not just a few) segments of vulnerable communities. For example, the poorest of the poor that are hit the hardest. Greater inclusion involving governments and the public sector need to be considered. Questions remain. What have we not yet done? What other strategies need to be considered? Who are the other relevant stakeholders that need to be in these conversations?

The Living Income Community of Practice, coordinated by Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), Sustainable Food Lab and ISEAL Alliance, is a vital platform for tackling such questions. Formalised in 2015, the community of practice acts as a platform for motivating actors across sectors to help close income gaps, so that smallholders can earn a decent standard of living as a basic human right. It drives multi-stakeholder discussion on common definitions and approaches to calculating actual and living incomes. Providing clarity and guidance on baselines and benchmarks are conducted. Transparency and data sharing among stakeholders is encouraged. Through the community, different actors in the living income space can share information about their efforts, including updates on upcoming living income studies, benchmarks and development activities.

Where are we today?

To better understand the income gap, some organisations, such as Mondelez and Fairtrade International, have embarked on measuring actual income levels. In addition, work has been done to calculate what a living income benchmark should be for particular commodities, in particular regions, and these can be referenced on the Living Income Community of Practice website. These questions are essential to define boundaries and targets for the short, medium and long-term interventions needed to raise incomes.

They also help to clarify the role that different actors, from public to private sectors, have in effecting change.

Over the last few years, significant strides have been achieved in some sectors, but more needs to be done. We still need more information to know with real certainty where we are or where we need to be regarding farmer incomes. To determine what farmers are actually earning, existing datasets have to be improved and verified, and data managers need to improve data transparency. We also require better information to assess the level at which farmer incomes allow for a decent standard of living and a sustainable sector. The Community of Practice provides clarity on the various methodologies and their applicability through published guidance papers.

Enabling smallholders to earn a decent living is critical to breaking the cycle of poverty and achieving the SDGs. But it is something that can only be realised by working together across supply chains, regions and sectors. Efforts to ensure a sustained and resilient living income for all are a topic more relevant than ever before. The time to make these efforts is now.

Sheila Senathirajah is Innovations Senior Manager at ISEAL Alliance and represents the Living Income Community of Practice.

Contact: sheila@isealalliance.org ; livingincome@isealalliance.org

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment