Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

The right to adequate food on the global agenda – a 30-year review

The global political breakthrough for the right to adequate food came with World Food Summit 1996 and the first paragraph of the Rome Declaration: “We, the Heads of State and Government, (…), reaffirm the right of everyone to have access to safe and nutritious food, consistent with the right to adequate food and the fundamental right of everyone to be free from hunger.” Several factors enabled this new level of political expression in support of a human rights-based approach to food security.

Triggering growing attention – the invisibility of human rights

The right to adequate food had been recognised as part of the right to an adequate standard of living in Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948 and in Article 11 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights of 1966. Ground-breaking conceptual work was done by Norwegian human rights scholar Asbjørn Eide in his study on the right to adequate food for the UN Human Rights Commission in 1986. The international human rights organisation for the right to food, FIAN, was founded in 1986 and embarked on international advocacy. Fresh dynamics set in when the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights started to work with a mandate as treaty body in 1987.

After the end of the Cold War, the general bias in public attention between economic, social and cultural rights on one side, and civil and political rights on the other, became an issue of discussion. A key shift was achieved with the UN World Conference on Human Rights in 1993 which recognised in Article 5 of the Vienna Declaration: “All human rights are universal, indivisible and interdependent and interrelated.” This fundamental recognition brought more political attention to economic, social and cultural rights.

New initiatives opened the way to connect human rights with food security and nutrition. In 1993, the UN Inter-Agency Standing Committee on Nutrition started a process on “ethics, nutrition and human rights”, with impulses coming from inside UN agencies, civil society and academics gathering in the World Alliance on Nutrition and Human Rights and some member states. The Civil Society preparatory conference for the World Food Summit (WFS), organised in Quebec/Canada in October 1995, agreed to include the promotion of the right to adequate food into its priorities for the preparation of the WFS and started a comprehensive advocacy strategy with governments and officials of the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

The WFS Plan of Action, adopted in Rome/Italy, then included a specific commitment (Objective 7.4.) that shaped the further process and set the agenda for the next ten years: “To clarify the content of the right to adequate food and the fundamental right of everyone to be free from hunger, (…) and to give particular attention to implementation and full and progressive realization of this right as a means of achieving food security for all.” Two major tasks resulted from this objective: clarifying the normative content, and developing policy guidance for implementation.

Developing contents and supporting implementation

The follow-up to the WFS focused on these two tasks. Civil society organisations drafted their own Code of Conduct on the Right to Adequate Food, which was presented in 1997, endorsed by hundreds of organisations, and used in the further advocacy and negotiation process. The UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which was asked by the WFS Plan of Action to do so, started working on its General Comment 12 on the right to adequate food, which was adopted in 1999 as an authoritative interpretation of the normative content. In 2000, the Mandate of the UN Special Rapporteur on the right to food was established by the Human Rights Council. In 2002, the proposal to negotiate Voluntary Guidelines to foster and give guidance to the implementation of the right to food was brought to the WFS+5 Conference, which endorsed the initiative.

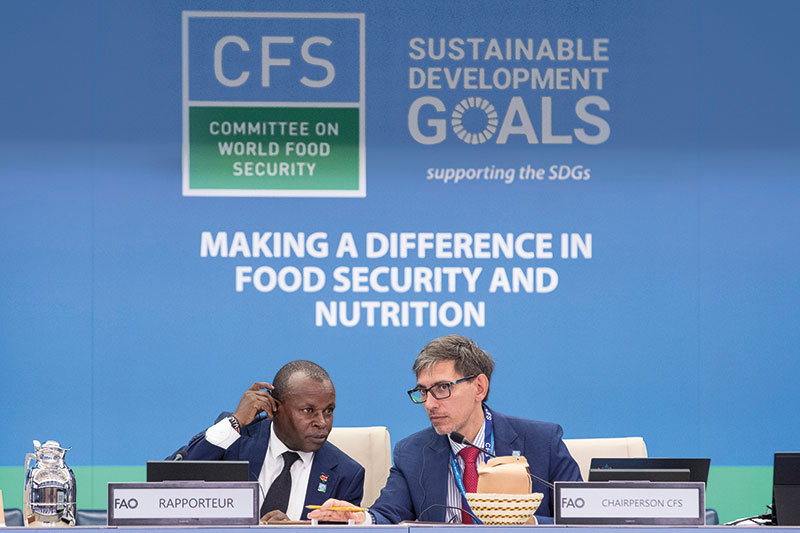

Between 2002 and 2004, the Committee on World Food Security (CFS) became the venue for the negotiations of the Voluntary Guidelines for the Progressive Realization of the right to Adequate Food in the Context of National Food Security. These were the first intergovernmental negotiations in Rome to actively involve civil society actors in such talks, although they only had the formal status of observers. The Right to Food Guidelines were adopted unanimously by all Member States of the FAO Council in November 2004. Hence, a global consensus document was reached on how to apply a human rights-based approach to food security.

From 2005 onwards, there was a strong focus on national application. The FAO Right to Food Unit was established to support countries in applying the Right to Food Guidelines in national policies, legal frameworks and programmes and was equipped with substantial resources over the next ten years. Many countries, governments, parliaments, civil society and Indigenous Peoples’ organisations, social movements, human rights defenders and academics collaborated and supported efforts on awareness raising, capacity building, policy initiatives, legislative or constitutional reforms or case-related justiciability and accountability campaigns.

Plenary Session of the Committee on Food Security’s 51st Session (CFS51) at the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization Headquarters. The role of the CFS as the global multilateral normative body for food security and nutrition has been widely recognised. Photo: FAO/ Giulio Napolitano

The Right to Food Guidelines successfully pioneered national policy implementation for economic, social and cultural rights. They also became a cornerstone of the multilateral governance reform on global food security, with the reform of the CFS in 2009 in response to the global food crisis in 2008. The progressive realisation of the right to adequate food was explicitly included in the Vision statement of the reformed CFS, and the social participation experience of the Guidelines negotiations was institutionalised in the new setting of the CFS – a milestone for governance with a direct rights-holder participation in UN bodies.

Controversies, decline, comeback?

However, the more influential the right to adequate food and its related human rights perspectives became in policies that directly or indirectly affect food security and nutrition, the more it got under attack. Even within the reformed CFS, delegates from several countries started to question the human rights mandate of the CFS, by arguing that it should not deal with human rights since this was an issue to be discussed by the UN human rights bodies in Geneva/Switzerland. However, the right to adequate food cannot be realised in isolation but is connected to the realisation of other human rights, such as women’s rights and the rights to health or housing.

Unfortunately, within FAO, the support from top management for the right to adequate food declined over the years. The FAO Right to Food Unit shrunk to a tiny team, highly committed and professional but without the necessary resources and political support for serving the institution to mainstream and implement the right to adequate food comprehensively into its programmes and collaboration with countries. In 2017, delegates from committed Member States founded an informal Group of Friends of the Right to Food in Rome, to join hands in defending and strengthening human rights perspectives within the CFS and the Rome-based agencies.

Recent developments seem to indicate that winds are changing. Influential countries from the Global South and North have expressed that the right to adequate food should again become a priority for FAO. The CFS Multi-Year Plan of Work for 2024–2027, which was negotiated in the first semester of 2023, is particularly strong in mainstreaming the right to adequate food throughout the upcoming years, connecting it to the 20th Anniversary of the Right to Food Guidelines, to cooperation with the three Rio Conventions on Climate Change, Biodiversity and Desertification, to the inequalities’ agenda, to the CFS global policy coordination function in response to food crises, as well as to the rights of food systems workers.

The Global Forum for Food and Agriculture (GFFA), hosted by the German Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture in January 2024, highlighted the importance and visibility of the Right to Food and the CFS in its Programme and final declaration. The Final Communiqué, which was signed by 61 Agriculture Ministers, called for renewed efforts to implement the right to adequate food as an international priority commitment, and to strengthening the CFS in its role as the foremost inclusive international and intergovernmental policy coordination platform, promoting the uptake of its policy outcomes.

Specifically, the Ministers “acknowledge the important contributions of FAO and the other Rome-based agencies during the past 20 years in supporting countries to implement the right to adequate food and encourage FAO to enhance its technical support to member states’ efforts to further promote the right to adequate food on the national level”.

Brazil’s new Global Alliance against Hunger and Poverty, to be launched in November 2024 at the G-20 Summit, includes specific provisions to advance the right to adequate food as essential part of this initiative which aims to transcend the G-20 membership. The outline of the new alliance explicitly recognises the CFS as the global multilateral normative body for food security and nutrition and includes the promotion of its policy outcomes as part of the intended support to participating countries.

An advanced normative framework of the right to adequate food

One of the major achievements of the Right to Food Guidelines, and the many years of thoughts and deliberations prior to them, is that they have inspired and contributed to the development of several other normative instruments in the realm of the UN. They have deepened the understanding and the interrelatedness of the right to adequate food in several policy areas which matter to many rights-holders and duty-bearers. In consequence, a more advanced and elaborate normative framework based on the right to adequate food has evolved.

One example is the Voluntary Guidelines on Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests (VGGT), adopted by the CFS in 2012. On land tenure issues, the VGGT have become the main normative reference that connects land tenure issues with the right to adequate food. Many of the other CFS policy outcomes of the last ten years have made significant contributions to further developed human rights-based standards in their respective areas, including on water, social protection, smallholders to markets, conflicts and protracted crises. One of the main normative and standard setting documents that should be highlighted in this context is the Voluntary Guidelines on Gender Equality and Women’s and Girls Empowerment, approved by the CFS in October 2023.

In parallel to the new instruments developed in the CFS, other normative instruments on areas dealt with at FAO and the CFS and with specific relevance for specific rights holder groups were developed in other UN Fora, for example: the UN Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), the UN Declaration of the Rights of Peasants and other People Working in Rural Areas (UNDROP), the FAO Voluntary Guidelines for Small-Scale Fisheries (VGSSF), and the ILO Policy guidelines for the promotion of decent work in the agri-food sector.

The advanced normative framework is certainly an achievement. It can guide state policies at the national and international level that are oriented to fulfil their human rights obligations. Today, the main task is to ensure that they are effectively used to foster the progressive realisation of the right to adequate food, particularly for rights-holders most affected and most at risk. The CFS has defined this use and application tasks as a priority area of the work plan 2024–2027, and this requires that all the committed hands work together. The other major potential of the advanced normative framework is that it provides guidance for transforming food systems towards more equity and equality, social participation and accountability, diversity and human rights coherence.

The new Right to Food Project at the German Institute for Human Rights

One of the crucial and urgent tasks of the international community is a human rights-based transformation of food systems. How can countries transform their food systems in such a way that all people can feed themselves adequately and that the limits and challenges of the triple ecological crisis – climate change, biodiversity loss and desertification – can be respected? This is a central concern of a project run by the German Institute for Human Rights which aims to support the progressive realisation of the human right to adequate food.

The project, which is supported by the German Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture, is being implemented in collaboration with committed actors of the international community, the United Nations, civil society and Indigenous Peoples. For the year 2024, the 20th anniversary of the Right to Food Guidelines, the focus is on strengthening the right to adequate food and to foster a human rights-based transformation of food systems in the relevant international fora, and supporting an enhanced use and application of the policy outcomes of the UN Committee on World Food Security (CFS) at national level. The project started in December 2023 and runs until the end of 2025.

Martin Wolpold-Bosien is Senior Researcher and Policy Advisor at the German Institute for Human Rights in Berlin. He would like to acknowledge the valuable comments received from Anna Würth and Michael Windfuhr.

Contact: wolpold-bosien@institut-fuer-menschenrechte.de