Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

The legacy of colonialism is still there

A description of the establishment of Indigenous Peoples’ rights ought to set out from a brief reflection on the formative context which justifies the special character of these rights. Especially in parts of the social sciences, in the course of a critical discussion of colonially influenced terminologies, the conception of “Indigenous Peoples” is often said to be based on an anachronistic stereotypification of the peoples it refers to as “primitive” or “primordial”.

A frequently quoted essay by British social anthropologist Adam Kuper sceptically reviewed the “widely accepted premises” that the descendants of the “original inhabitants” of a country ought to be endowed with privileged or even exclusive rights to land and natural resources. In this context, critics also emphasise that these rights are based on an idealistic view of people living together with nature in harmony. Here, it is said, the ancient notion of primitive peoples is revived in a new guise. Such objections overlook the colonial politics background the more recent debates on the rights of Indigenous Peoples are based on. The legal status of those populations for whom the term “Indigenous Peoples” is used relates to the spreading of colonialism which originated in Europe and, simultaneously, to developments of so-called international law which are directly linked to this colonial globalisation. In the 16th century, Spanish theorists representing Christian universal natural law theory had still assumed that the people encountered in the “New World” formed gentes, i.e. natural political communities. In a similar manner, in the early English or (from 1707 on) British colonisation history of North America, “peace and friendship agreements” with Native American groups play a role. These groups were indeed referred to as “nations” in a true legal sense. It was only in the course of the 19th century, following the Latin American countries’ gaining of independence and the across-the-board spreading of European colonial empires in Asia, Africa and Oceania, that a single model of political organisation asserted itself: the sovereign territorial state of the “European” type.

The political predominance of this model had already been anticipated by the philosophy of enlightenment. For example, the brilliant English state philosopher John Locke had upheld the notion that the native inhabitants of North America lived in a “state of nature” and had developed no civil and hence also no political society. The 18th and 19th century scholars of international law focused the fundamental assumption that peoples had a right to political self-determination, an assumption which had existed long before the founding of the United Nations, more and more on the notion that this right could only be exercised in the form of a territorial nation state. It was this basic concept that inspired state-oriented nationalism in Europe, spread it throughout the world and resulted in its world-wide superpositioning of all political organisational forms which did not correspond to the features of this European “nation state” in the context of the colonial system.

Political structures of some non-European societies, ranging from Christian Abyssinia through the (non-Christian) Ottoman Empire and Persia to China and Japan, grew into the so-called concert of civilised nations. However, the many hundred or even thousand political structures of other human societies not only experienced colonisation but also far-reaching ignorance of their own existence in the context of a new, “international”, global order. One paradox and tragic aspect for these societies is the circumstance that the very so-called de-colonisation in the second half of the 20th century did not recognise or revive non-European political organisational forms but once and for all consolidated the idea and form of the European-style territorial state.

Against this background, just as the world was almost fully covered and split up by independent states, activists from colonised population groups living far apart from one another – like the Saami of Northern Europe, Australian Aborigines, First Nations from Western Canada – made themselves noticed and demanded the core legal concept which had inspired world-wide decolonisation in the post-founding era of the United Nations: the peoples’ right to self-determination. The two core human rights covenants of the United Nations recognise this right, formulated identically in their Articles One, and this recognition was now – also – being taken up and demanded by the Indigenous activists.

International sets of regulations

In 1982, in the context of the then United Nations Economic and Social Council, for the first time, a body was formed the mandate of which included working out appropriate standards for these groups, which were officially still referred to as populations. The Working Group on Indigenous Populations (WGIP), as this new subsidiary organ was called, became the very first United Nations body in which representatives and members of the population groups concerned were able to immediately participate in developing international legal standards relating to them.

A tedious process began. Nevertheless, the preparatory work of the WGIP ultimately flowed into what the United Nations General Assembly adopted as the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) in 2007. This Declaration comprises 46 articles and a long preamble section explaining its objective and how it is embedded in the system of international human rights. The UNDRIP regulations affect virtually all areas of life, ranging from land, territories and natural resources through political autonomy and self-determination to health systems, traditional cosmovision and media. However, the root idea is that all standardisations are aspects of the Indigenous Peoples’ right to self-determination, which is above all to be applied on the basis of independent indigenous institutions. This is why references are again and again made to supporting and developing peoples’ own indigenous decision-making institutions or independent political, economic and social systems.

Although the Declaration is not a formally legally binding instrument, experts maintain that in many respects, its contents put already valid international customary law into concrete terms.

In parallel to the drafting process of the Declaration, in the context of a Specialised Agency of the United Nations, the International Labour Organization (ILO), with Convention C169 (the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention), a binding agreement on the rights of Indigenous Peoples was created. This Convention, which was adopted in 1989, consists of 44 articles and is to secure the right of Indigenous Peoples to decide their own priorities for the process of development as it affects their lives, beliefs, institutions and spiritual well-being and the lands they occupy or otherwise use. C169 takes up the aspect that the ILO – in accordance with its mission as the responsible international organisation for social issues – had already long seen itself as responsible for the social and labour situation of so-called native populations and, to this end, had enforced several international ILO Conventions. However, these Conventions were not focused on securing their status as independent political units, but – on the contrary – on supporting the integration process of indigenous populations into general working and economic life while preventing hardships.

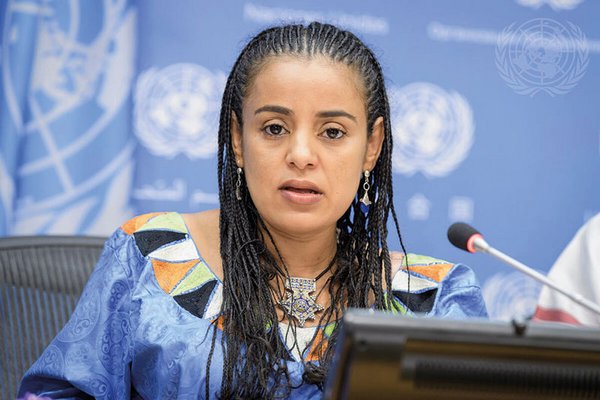

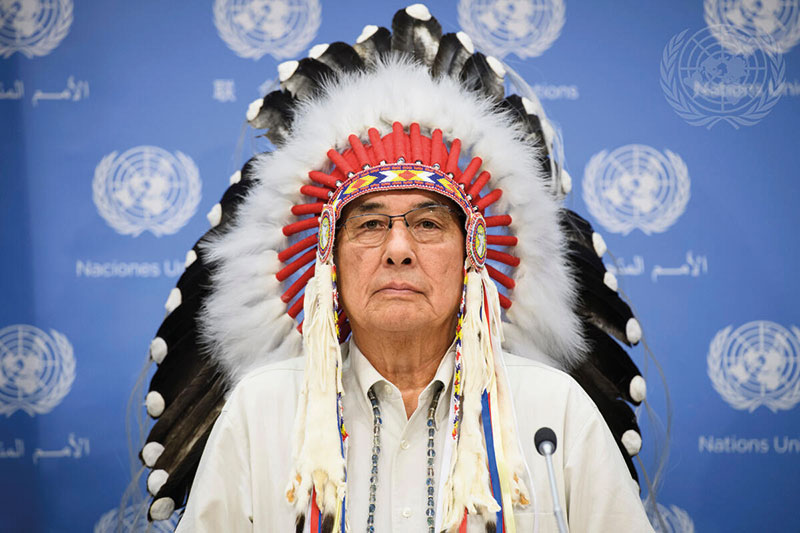

Grand Chief Wilton Littlechild, a Canadian lawyer and Cree Chief, at the tenth anniversary of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Photos: UN Photo/ Manuel Elías

The consultation and participation procedures stipulated in Articles 6, 7 and 15 form the centrepiece of Convention C169. They are to ensure the participation and voice of Indigenous Peoples in state regulations and projects immediately affecting them and their rights directly. Consultations are to be held in a form oriented on achieving agreement to the proposed measures, although no right of veto is provided for the Indigenous Peoples concerned. Neither is there any mention – on purpose and in contrast to the declaration – of these peoples’ “right to self-determination”. However, in terms of contents, the UN Declaration and the ILO Convention C169 complement each other and form robust foundations for the internationally recognised rights of Indigenous Peoples. While, as a non-binding instrument, the Declaration is not equipped with a legal complaints procedure, the Convention is anchored in the ILO monitoring and complaints system. As a special feature among international organisations, in the ILO system, in addition to the representations of the state governments, the national representations of employer and employee organisations also play a leading role. In practice, it is therefore possible for e.g. national trade unions to lodge complaints (called “representations”) referring to violations of rights based on the Convention with the ILO Governing Body, which is responsible for such issues. However, indigenous persons or organisations as such are excluded from the organisation’s complaints and monitoring system.

Regional protection systems

In addition to the United Nations international human rights system, there are regional protection systems. The Inter-American Human Rights Convention of the Cold War era, which entered into force in 1978 and originally had a strongly “anti-communist” orientation, mentions neither Indigenous Peoples nor their rights. However, Article 21 of this instrument states: “Everyone has the right to the use and enjoyment of his property.”

In an important ruling (Awas Tingni v. Nicaragua, 2001), the Inter-American Court of Human Rights extended this protection provided for by Article 21 to communal landed property not based on state civil law but on traditional customary law of an Indigenous People. Awas Tingni is an example of a regional human rights court’s jurisdiction referring to and elaborating general human rights provisions to enhance the protection of Indigenous Peoples. In similar rulings, both the Inter-American Court of Human Rights and the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights have had to judge new constellations of cases and, in this context, regarding the extent of legal protection provided, have occasionally had to go beyond Convention C169 and the UN Declaration. In a presently pending case (Tagaeri y Taromenane v. Ecuador), for the first time, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights is having to judge the rights of an indigenous group living in so-called voluntary isolation and therefore being unable to directly participate in the procedure.

All in all, the core areas of the rights of Indigenous Peoples outlined above show that privileges for groups stereotyped as alien, or fundamentally distinguishing them from a “cosmopolitical modernity” owing to the cultural purity which they have been attributed, are not at issue here. Rather, self-determined control of economic, social and cultural development is to be ensured. Such development is only possible through simultaneously ensuring and elaborating Indigenous Peoples’ own political institutions, which have so far been concealed by the cloak of the colonial international system. It contributes to breaking up the monopoly status the territorial nation state holds because of colonialism, and creating a pluralistic and de-colonial international order in which the political institutions and organisations of Indigenous Peoples come out of legal exclusion and epistemological marginalisation and they themselves are attributed the status of International Law subjects without being states in the conventional sense.

Environmental law regulations

Through the development of the central international instruments, the contents of Indigenous Peoples’ rights have received relatively clear – and by and large rarely disputed – contours. Presently, however, the important challenge of what outreach the purview of these rights has poses itself. To round off this topic, two important levels of this current challenge are to be addressed. Environmental law regulations are conventionally based on state legislation, which in turn is often oriented on the state of the art and insights in natural science. The apparent “objectivity” of western science eclipses the extensive knowledge of Indigenous Peoples regarding biological diversity and local ecological conditions. Whereas the Convention on Biological Diversity of 1992 already contains a reference to the respect and preservation of knowledge, innovations and practices of “indigenous communities” which are relevant for the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity, this protection is only recognised in the Convention provided that it is established in state law. The institutions of Indigenous Peoples which are based on handed down experience are not explicitly recognised and safeguarded. States reserve the right to decide whether or not to even include traditional knowledge and practices of Indigenous Peoples in their environmental policies.

A similar deficit becomes particularly apparent in connection with the designation of Protected Areas. Ever since the concept of Protected Areas evolved in the 19th century, designating national parks and similar protected areas has gone hand in hand with the notion of seeking to conserve pristine nature – devoid of humans. Most of the Protected Areas set up throughout the world, including the most extensive ones, were designated in regions which were regarded as no man’s land in a legal sense, and state institutions were entrusted with their administration.

This had a double effect. The institutions of the population groups in the regions concerned were denied a relevant political existence of their own. Rather, the nation states laid claim to extending the purview of their legal system to these regions. Thus not only the natural resources that needed to be protected but also the members of the societies living there were made subject to state law. Protected areas were turned into a vehicle of forced assimilation and into regions designated for a “civilising mission”; an “indigenisation” of these populations is performed here via political exclusion. Paradoxically, this results in the traditional knowledge and practices contributing to the ecological balance of these regions being ignored, made illegal and, ultimately, destroyed.

At the 2022 Biodiversity Conference, states adopted the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, according to which conservation areas are to be set up across 30 per cent of the planet’s surface by 2030. While the document provides – albeit with a very weak formulation – for respecting the “rights of indigenous peoples and local communities”, it remains to be seen whether Indigenous Peoples will indeed also be able to enjoy the right to self-determination in the context of global environmental politics.

The private sector and Indigenous Peoples’ rights

The immediate relevance and binding force of Indigenous Peoples’ Rights for non-government economic actors, especially in transnational business activities, is a second, important challenge regarding the outreach of Indigenous Peoples’ rights.

Even the immediate purview of the universally recognised human rights still remains disputed when it comes to private transnational actors – despite the circumstance that activities performed by power generating companies, agricultural corporations or firms operating in the area of infrastructure development often result in particularly crass impairments of human rights such as resettlements, uncontrolled immigration, the destruction of habitats and the food base, etc. For more than a decade, a debate has been intensifying at global level on the obligation of states to legally require that firms under their jurisdiction observe human rights. However, regarding contents, the contours of this debate are by no means clear. On the one hand, it focuses on whether such regulations only have to address core human rights or, for example, also ought to be extended to Indigenous Peoples’ rights, and on the other, to what extent corporations are also responsible for the companies participating in their international value chains (subsidiaries as well as regular business partners).

Developments in this area are highly topical, and are still in progress. In mid-2023, a European Union Regulation entered into force stipulating in a binding manner that a number of commodities brought into circulation in the EU must not contribute to deforestation and degradation of forests in the EU and elsewhere in the world. In their value chains, firms are legally bound to the objectives of this directive. In several instances, the recitals for the Regulation address in detail the close relationship between Indigenous Peoples and forest areas, for instance serious consequences of the destruction of forests “for the livelihoods of the most vulnerable people, including indigenous peoples and local communities who depend heavily on forest ecosystems”. However, the core provision of the Regulation’s Article 3 stipulates that relevant products may only enter the (EU) market if they are deforestation-free and “have been produced in accordance with the relevant legislation of the country of production”. So it is up to the exporting country to determine how and whether Indigenous Peoples’ rights are protected or even considered. This example shows that despite progress made in the true human rights sector, international law continues to be based on a largely colonially shaped exclusivity of territorial nation states.

René Kuppe is a retired law professor from the University of Vienna/Austria whose academic work is centred on the rights of Indigenous Peoples, with a focus on indigenous legal philosophies, indigenous legal systems, protection of traditional indigenous beliefs and religions, and sustainable development and Indigenous Peoples. René is also a Board Member of the International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA), Copenhagen/Denmark.

Contact: rene.kuppe@univie.ac.at