Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

The Indigenous Navigator – data for and by Indigenous Peoples

To respect, protect and fulfil the human rights of Indigenous Peoples, states have, among others, an obligation to monitor the degree to which national strategies, policies and plans address the inequalities and discrimination that many indigenous communities face. To do this, states need reliable data on the situation of Indigenous Peoples. The lack of this data invariably impacts on the adequacy of state measures in both recognising the contributions of Indigenous Peoples and implementing their rights.

The Navigator and its main tools

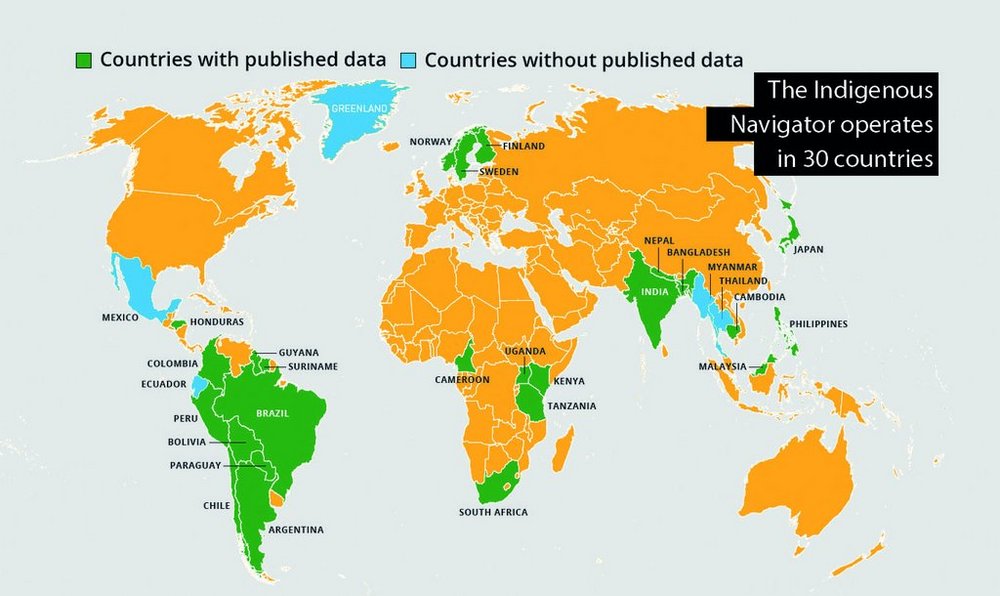

To address this gap and support states’ efforts in this regard, the Indigenous Navigator initiative works with Indigenous organisations and their communities to generate data on the status of the implementation and realisation of their rights based on international human rights and labour standards. As an online portal, the Indigenous Navigator provides Indigenous Peoples and their organisations with free access to an internationally recognised framework and set of data generation tools and guidance. The tools are grounded in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), ILO Convention 169 (ILO C169) and binding human rights instruments. The main tools of the Indigenous Navigator are described in the following.

Indicator framework

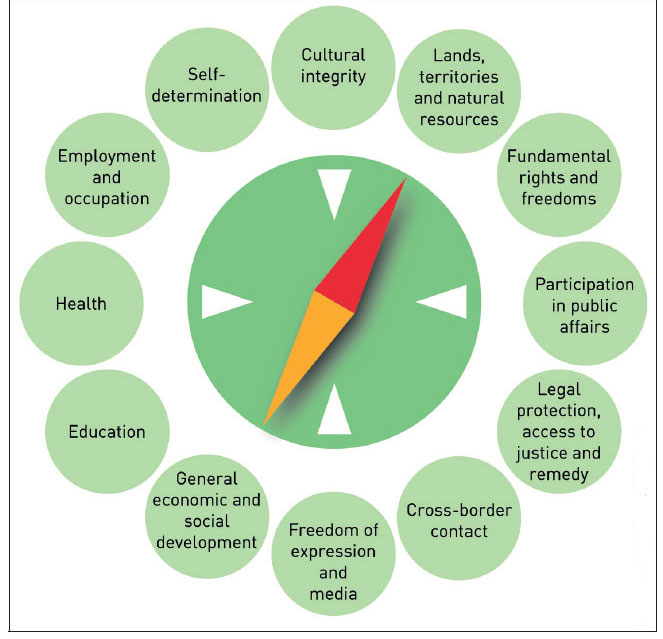

The indicator framework is the backbone of the Indigenous Navigator. It was developed using the methodology for the human rights indicators of the United Nations Human Rights Office (OHCHR). The indicators are structured around the twelve thematic domains as reflected in UNDRIP (see Figure). They were developed by further identifying the sub-categories of human rights covered under each of these domains and clarifying the key attributes or characteristics of the rights in question. Three types of indicators were then developed to monitor different aspects of state obligations to respect, protect and fulfil these rights:

The structural indicators measure the extent of the state’s commitment to Indigenous Peoples’ human rights. In other words, they monitor whether the state has ratified the relevant treaties or has adopted the necessary national legislation or policies. This includes, for example, whether there is a recognition of Indigenous Peoples’ distinct identity in the constitution or national legislation based on self-identification.

- The process indicators measure the efforts made by states to implement these commitments, e.g. whether they have developed adequate programmes and budgets to implement their obligations. An example of such a process indicator is whether public funds from central or local government have been allocated from central and/or local government to Indigenous Peoples’ self-government institutions.

- The outcome indicators measure the degree to which Indigenous Peoples actually enjoy these rights in practice, e.g. whether they report that there are consultations with their autonomous institutions before approval of measures and projects that may affect them.

The indicator framework, as an independent tool, can be used in analyses and baselines to identify gaps in the implementation of UNDRIP and as a basis for policy dialogue.

Comparative matrix and data base

The comparative matrix exemplifies the methodology described above, showing how indicators are linked to the twelve domains and sub-categories. It also reflects how these indicators have been developed into specific questions which can be found in questionnaires (see below) on the portal. Importantly, it illustrates the direct linkages between UNDRIP and legally binding international human rights and labour standards. Since UNDRIP does not provide for an institutionalised monitoring mechanism, these linkages to binding instruments with monitoring mechanisms allow Indigenous Peoples and other interested stakeholders to use data collected based on the provisions of UNDRIP in the reporting and monitoring processes established in the respective legally binding instruments for increased accountability. These include, among others, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women.

National and community questionnaires

Based on the indicator framework presented above, the Indigenous Navigator includes two questionnaires:

- A national questionnaire for use in country profiling. It is designed to assess the level of recognition and implementation of UNDRIP in a particular country, focusing primarily on the existence of laws, policies and programmes.

- A community questionnaire for use by indigenous organisations and communities. This questionnaire helps document the human rights situation of particular indigenous communities.

Indigenous Navigator Index

Two Indigenous Navigator indices have been developed to assist in the visualisation of the results from the data collection. They allow for the ranking of countries’ performance in recognising and implementing Indigenous Peoples’ rights in line with UNDRIP. These indices can be used in briefings, reports and publications to highlight gaps in the states’ implementation of Indigenous Peoples’ human rights. The Index Tools assign a numerical value to the responses of the questions chosen from the two questionnaires respectively. A “better” response option means that there is a higher level of human rights compliance or enjoyment of the right than a “worse” response option. The higher the level of human rights compliance, the higher the score of the response option in the index. To make the response options of the different questions comparable, the scores have been “normalised”, meaning that the value ranges from 0 to 100 depending on the level of recognition and implementation of Indigenous Peoples’ rights. The category score is calculated as the average score (simple mean) of the questions included in the given sub-category for both the national and the community questions. The same goes for the domains, where the index value of a domain is given by the average score (simple mean) of the included categories. The overall index score is a simple mean of all twelve domains.

When an Indigenous Navigator Community Index and an Indigenous Navigator National Index have both been generated for the same country, a comparison of the two will show whether communities’ experiences of actual respect for their rights reflect the level of recognition of their rights in national legislation, policies and programmes. Likewise, index values can be compared across communities, across countries or over time if the data gathering is repeated.

Data explorer and index explorer

Anyone can explore the data on the online portal once consent has been obtained for making the data public. The data explorer visualises all the submitted answers and comments, while the index explorer allows users to explore the calculated index values and implementation status.

From sensitisation to self-determined development

The Indigenous Navigator has been used in the following ways by Indigenous Peoples:

Sensitisation and data collection: At the community level, data is collected through a full community meeting, a focus group or a community seminar. The process is aided by a facilitator and often combined with training sessions. Data collection must respect the principle of free, prior and informed consent, including consent to upload data to the Indigenous Navigator Data Portal. The community must be fully informed about external uses of the data and any further developments. Results must remain easily accessible to the community, which the data is meant to serve. Experiences to date have shown that applying the Indigenous Navigator tools has had an empowering effect on Indigenous communities.

Advocacy and policy influence: The data is used by Indigenous Peoples to produce data-driven reports and policy briefs for engaging a range of stakeholders. The latter have included national governments, UN agencies, development agencies, the private sector and other civil society organisations. The Indigenous Navigator has already facilitated improvements at national level. For example, in Nepal, advocacy efforts using the Indigenous Navigator have led to a series of reforms. Provincial and local governments have, for instance, started consulting Indigenous Peoples in local development planning and have allocated funds for the general socio-economic and cultural development of Indigenous Peoples.

Self-determined development: Key to the Indigenous Navigator initiative is supporting Indigenous Peoples to create their own development paths, informed by their own cultural values, traditional knowledge and cosmovisions. The collected data is thus also used to assist Indigenous Peoples in designing and implementing projects that address their specific needs and challenges, as revealed in the data. The initiative provides small grants to Indigenous communities to facilitate these community-led projects. For example, in Palmira, in the Lomerío Indigenous Territory in Bolivia, the indigenous communities identified that there was no clear policy on implementing bilingual intercultural education in the territory. They consequently decided to embark on a project to revive the Bésiro language through a small grant and were able to study the language alongside Spanish.

Carol Rask is currently Team Leader for the Equality and Non-Discrimination Team in the Human Rights and Sustainable Development Department of the Danish Institute for Human Rights in Copenhagen. She holds a Masters in Human Rights.

Contact: cara@humanrights.dk

The Indigenous Navigator is a collaborative initiative co-ordinated by five partners: Asia Indigenous Peoples Pact (AIPP), Forest Peoples Programme (FPP), Tebtebba Foundation, the International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA) and the Danish Institute for Human Rights (DIHR). The author would like to thank the Consortium for their valuable input to this article.