Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Haki Ardhi – the women’s land rights reporting tool

While women are often taking care of their family’s food and nutritional needs and managing household resources, they account for less than 20 per cent of landowners world-wide. In some Asian and African countries, this figure is even lower. Despite favourable legislation in recent years aimed at protecting women’s land rights, these rights are often effectively denied due to deeply rooted patriarchal norms and women, men and powerholders lacking awareness of such rights. In addition, customary land governance systems often do not allow women to inherit land, making access to justice and dispute resolution related to land difficult.

The genesis of women’s land rights reporting in Kenya

This inequality is also evident in Kenya, where more than 70 per cent of women do not have title deeds. As a result, they are at risk of being displaced in the case of divorce or the death of their husbands. Widows and unmarried women in particular have difficulty claiming the land of the deceased and are often unfairly excluded from secure land rights. This denial not only jeopardises survival but also violates fundamental human rights, including access to justice, redress, compensation and participation.

In response to the urgent need to address climate challenges, to reduce or compensate carbon emissions, Kenya is (becoming) a hotspot for external investment and global initiatives for carbon markets. This leads to land-intensive projects that risk disregarding the rights of rural communities and especially the rights of indigenous people and women. To tackle these risks, it is imperative for communities and individuals to be able to monitor and report on land rights infringements, as well as to ensure that project implementers and duty bearers are held accountable for upholding and protecting these rights. Responding to the increasing threats to tenure rights, the idea of Haki Ardhi (Swahili: Land Justice) was born. By providing a community-based platform for women to report land conflicts and receive support, Haki Ardhi not only becomes a transformative tool for women; by addressing land conflicts and advocating for women’s land rights, it seeks to bring about change benefiting the community as a whole.

Accessibility for everyone

Haki Ardhi was jointly developed by TMG Research, Kenya Land Alliance and Rainforest Foundation UK between 2022 and 2023. It integrates digital reporting to document evidence, data collection and processing with innovative, social support structures that are already existing and well-established. The tool takes a multi-layered approach to empowering individuals and communities by providing accessible reporting options through multiple channels, including a toll-free, automated SMS hotline (accessible via standard mobile phones), paralegals and community workers, and office consultations. These different reporting channels ensure inclusivity and cater to the varying levels of technological literacy among women. Beyond reporting, the tool can equip community-based organisations with data to provide targeted support to women affected by rights violations and provide evidence of recurring or urgent issues to conduct targeted advocacy work and hold those responsible accountable.

Currently, the Haki Ardhi Rights Reporting Tool is being piloted in two Kenyan counties that are struggling with widespread violations of women’s tenure rights. Three community-based organisations, one in Kakamega (Shibuye Community Health Workers) and two in Taita Taveta (Taita Taveta Human Rights Watch and Sauti Ya Wanawake) counties, are actively using Haki Ardhi and offering reporting options. So far, through concerted outreach campaigns and radio broadcasts, the tool has successfully reached and engaged with more than 1,000 women, enhancing awareness and support.

One of the key achievements of Haki Ardhi is that it puts monitoring and reporting directly in the hands of communities or community-based organisations, allowing them to collect their own data in a decentralised way and use it according to their own priorities and needs. This is in stark contrast to the usual top-down monitoring and reporting practices where state actors or companies collect data, and it suggests that Haki Ardhi has potential for widespread adoption, particularly among Indigenous Peoples and local communities.

The idea of reporting via Haki Ardhi goes beyond individual cases. Civil society organisations (CSOs) can use the data generated to consistently monitor and formulate advocacy strategies and address systemic issues that contribute to the violation of land rights. So far, the tool has made contributions in two key areas. Firstly, it has successfully identified the prevalence of women’s tenure rights violations in two Kenyan counties (see Box). Secondly, community-based organisations and the national umbrella body (Kenya Land Alliance) have effectively channelled targeted support to women who have experienced infringements on their rights.

Alarming trends in forced evictions reported

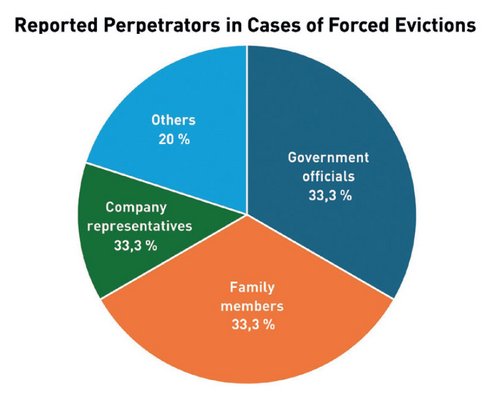

Reporting on forced evictions and interference in land management processes through Haki Ardhi reveals a concerning reality in Taita Taveta and Kakamega counties. From June 2023 to February 2024, 124 cases were reported. The specific figures highlight the urgent need for comprehensive measures to protect the rights of individuals and communities. The numbers show that forced evictions are an increasing concern in both counties. The reported perpetrators varied, ranging from government officials (33.3 %) and family members (33.3 %) to company representatives (13.3 %) and others (20 %).

The in-person consultations further highlighted the gravity of forced evictions. A striking 95.3 per cent of cases occurred on private or family-owned land, with 4.65 per cent affecting community-owned or communal land. Almost 56 per cent of reporters were widowed, emphasising the vulnerability of this demographic. But the impact on rural families goes even further as 54 per cent of cases involved children. In 51 per cent of cases, violence was not reported, but nearly 34 per cent involved verbal violence, and almost 14 per cent involved physical violence, which is a significant number showing signs of gender-based violence connected to land conflicts. Intra-family land issues are usually standing out. Also, the reported cases confirm that husbands were identified as the perpetrator in roughly 34 per cent of violent cases.

From all reported cases, more than 51 per cent of individuals had already been displaced from their homes or lands, illustrating the urgency of the situation as these women face serious problems in managing their livelihoods. Additionally, nearly 63 per cent reported seeking assistance by visiting government offices, emphasising the need for intervention at the institutional level. Since June 2023, when the tool was first used, first cases have been resolved in favour of the survivor. In most cases, community mediation and/or judicial proceedings have been used to solve the cases, with the first one usually being preferred.

The Haki Ardhi tool has been well received by powerholders, who have been actively and consistently involved since the inception of its development and implementation. Local chiefs perceive the issue of women’s land rights as an urgent and unresolved problem, one that they also recognise as relevant to their own political roles and interests. Men in the community actively participate in awareness-raising activities related to the Haki Ardhi tool. While some initially expressed concerns about their own rights, many have shown a willingness to engage in discussions about the urgent need for better protection of women’s land rights.

Moving ahead

The Haki Ardhi tool builds on existing community structures and support actors. Addressing land rights violations can only happen through improved governance and accountability processes. A safe reporting space is necessary to minimise the risk of escalating conflicts and violence. Haki Ardhi has the potential to address the emerging challenge of “green grabbing” through actively involving communities in countering exploitative practices and ensuring they can safeguard their rights. Given the ongoing land rush and the growing need for climate action through land-based interventions, it can contribute to justice and accountability. By providing them with a tool for monitoring and reporting, Haki Ardhi also enables Indigenous groups to protect their ancestral lands from encroachment and exploitation. This is particularly important as Indigenous Peoples are often disproportionately affected by land grabbing and environmental degradation, which threatens their cultural heritage and traditional livelihoods.

Accountability based on the ability of communities and individuals to monitor and report infringements of their rights plays a central role in the concept of “just transition”, ensuring both environmental sustainability and social equity. There is a growing focus on rights-based approaches to implementing the three Rio Conventions. For example, the Convention on Biological Diversity recognises the important role and contribution of Indigenous Peoples and local communities as custodians of biodiversity. Goal 22 specifically aims to ensure the full, equitable, and inclusive representation and participation of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in decision-making. In this endeavour, reporting and monitoring tools like Haki Ardhi are pivotal in empowering marginalised communities and fostering inclusive and sustainable land governance for all.

Frederike Klümper, a land tenure expert, leads the Land Governance Programme at TMG Research in Berlin, Germany. She has previously worked as an adviser and researcher for various organisations in Europe, Africa and Central Asia in the social accountability and resource governance field. Frederike completed her PhD at the Leibniz Institute of Agricultural Development in Transition Economies with her thesis on water and land governance in Tajikistan.

David Betge is Project Coordinator SEWOH Lab and Early Warning Systems at TMG Research. David spent five years in the Netherlands where he was a land rights and peacebuilding adviser for the international relief and recovery organisation ZOA. For his PhD studies at the Free University Berlin, David conducted research on redistributive land reforms in India and South Africa.

Contact: frederike.kluemper@tmg-thinktank.com