Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Drought Cycle Management for building resilience and food security

Based on various characteristics such as severity, duration, spatial extent, loss of life, economic loss, social effect and long-term impacts, several studies find that drought is the most far-reaching of all natural disasters. In the context of poverty and food insecurity as well as political instability, drought and its associated impacts is responsible for more deaths and displacement of people than any other natural disaster. The adverse impacts of drought are particularly serious for the poorest and most vulnerable in the drylands of developing countries whose economy relies on rain-fed agriculture and pastoralism.

The channels through which drought affects these vurnerable households are multifaceted and complex: they include lack of water for people and livestock, pasture and crops, energy, food availability and the rise in food prices, loss of lives and livelihoods, and assets. They fuel local conflicts around natural resources. And, while it is contested whether it leads to or amplifies larger conflicts and mass migration in the short run, there can be no doubt that in the long run, an increase in the frequency and severity of droughts would do exactly that.

EssentiallY natural, socially constructed

The reasons for the emergence of droughts are essentially natural – droughts have accompanied humankind from the very beginning and have been conceptualised one of the apocalyptic riders. As humans have increasingly shaped their environment however, drought risk has at least in part been socially constructed. Deforestation, forest fires, overgrazing, soil mining, land and vegetation degradation and water mismanagement lead to increased susceptibility to droughts, foster the drying of soils and water runs, overexploitation of groundwater reservoirs and, in sum, reduce the resilience of the landscape and of people along with the natural resources they depend on. In addition, the creeping and multi-faceted nature of droughts, often concentrated in rural areas, coupled with the lack of systematic recording of drought impacts does contribute to its reduced political and economic visibility and this in turn reduces the willingness to address underlying risks.

In the coming decades, drought is projected to increase in severity, frequency, duration and spatial extent, at the same time as the world’s land areas are expected to be drier overall in the 21st century. This will have severe consequences for people in poor countries and particularly in rural areas with arid and semi-arid lands which are extremely susceptible to droughts. It may be noted that recent simulations show that even the food security of developed countries may be threatened by droughts if they hit various large global production areas – such as United States and China for maize – simultaneously, which has never happened in historical times but becomes a possibility under climate change.

While the general process of economic development helps to alleviate the negative effects of droughts, this route is (too) long for developing countries, and will not be enough. Economic development itself can be compromised by intense and frequent droughts, and certainly local development is at risk. In addition, the effectiveness and efficiency of ad hoc drought management approaches – only coming into action with emergency measures when drought strikes – are low and long-term impacts are often not, or cannot be, considered.

Thus, proactive approaches are needed to increase the resilience of people, ecosystems and societies against droughts. In developing countries, food security should be at the core of national drought policies and a strong driving force in the fight against drought at all levels.

Drought resilience, preparedness and cycle management

The implementation of national drought policies based on the principles of risk reduction can mitigate the impacts of droughts. Such principles and their implications for action are spelt out in international voluntary agreements such as the Hyogo and the Sendai frameworks for disaster risk reduction and the seminal 2013 High-level Meeting on National Drought Policy. Based on these various international frameworks, the following “three key pillars” of drought risk reduction can be specified:

- Implement drought monitoring and early warning systems.

- Assess drought vulnerability and risk.

- Implement measures to limit impacts of drought and better respond to drought.

These pillars can help countries prepare better for, respond to and recover from drought by reducing exposure and vulnerability to drought, increasing resilience, and transferring and sharing drought risks. They have to be translated into national drought policies according to the specific needs, conditions and vulnerabilities, priorities and options of a country.

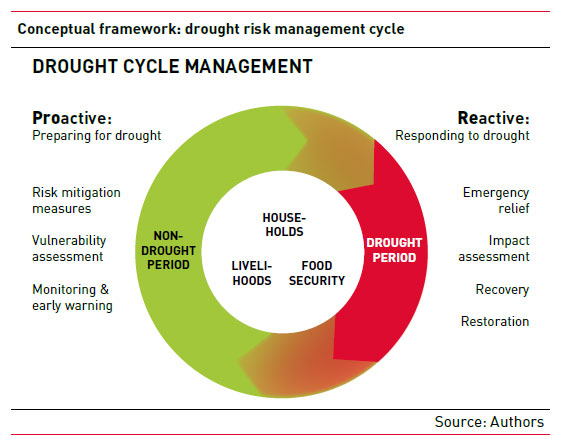

Drought is a complex, recurrent and slow-onset phenomenon. Unlike other natural disasters, such as floods and earthquakes, it takes long to realise that a drought – length, severity and extent – is in the making with implications for action to limit the impacts. As with all disasters, the disaster-free times should be used to build up resilience, while interventions during the drought times must be special in as far as they have to respond as early as possible, with due consideration of the quality (certainty) of the early warning systems and the evolving drought conditions. Yet, drought interventions should also be designed and implemented in a way to prepare for the next cycle. This leads to the concept of drought cycle management (see Figure) where proactive and reactive measures are interdependent and function in an integrated manner.

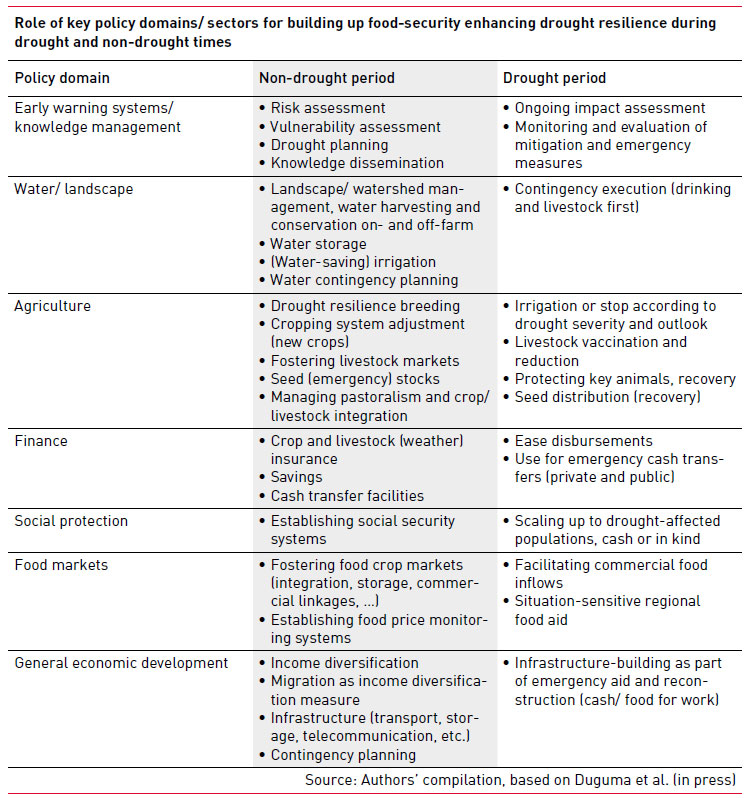

A comprehensive list of policy areas required to tackle food insecurity in drought-prone areas is shown in the table on page 31. Many sectors are involved: water, land and other natural resources, agriculture and food trade, social security, economic development and infrastructure, to name only a few. Other domains, such as energy and health, may also be heavily affected by droughts and require good preparedness plans and management.

It is necessary to build flexibility into such concepts. Droughts are slowly creeping phenomena whose (accumulated) impacts not only depend on precipitation but also on water storage, access and consumption, as well as on specific target systems. Thus, it is difficult to determine when exactly they start and end, especially as there is no universal definition of drought. Smallholders and poor consumers may be affected earlier than commercial farmers and the wealthy. While waiting to see how drought conditions evolve, “no- or low-regret” measures have to be taken early on for various target systems and groups, which can be adjusted according to the best available and updated information and risk scenarios. For instance, food stocks can be built up through local storage or international purchases, including by the private sector. This requires reliable data on future crop availability and demand. Water can be used for irrigation to overcome dry spells or short-term droughts but may have to be reduced to the most essential uses during longer droughts if water reservoirs become depleted. Vaccination and livestock reduction campaigns can be set in motion early on to avoid price collapse; and social safety programmes can be scaled up during drought periods, providing cash or food depending on food market conditions (see also articles "Make social protection schemes work for drought resilience: lessons from Ethiopia’s PSNP" and

"Building resilient livelihoods through economic empowerment – An example from Malawi").

Special treatment may be required for particularly vulnerable groups of drought-affected people and ecosystems. For example, specific strategies are often necessary for pastoralists who very often live in particularly drought-vulnerable arid areas. Pastoralism has in fact often been the best traditional adaptation strategy in these regions. In more recent times, the flexibility in time and space as well as livelihood options for pastoralists have been shrinking. New trends such as population growth, education, or changes in income sources and consumption habits have pushed for further structural changes. In these settings, improving the resilience of pastoralists against drought requires maintaining a particularly difficult balance between keeping up traditional ways of life and the economy and the shift to alternative livelihoods. Also, women are often affected by drought in ways substantially different from men.

Policy coherence and co-ordination

Policy coherence and coordination for drought resilience is particularly important and at the same time difficult to achieve because it touches upon many dimensions: sectors, various decision-making levels, time, socio-economic and technological transitions, etc. Bottom-up solutions to drought resilience are preferable because they are more compatible with aspirations and local knowledge (particularly for pastoralists), but all too often, they face limitations. Economic diversification away from income sources reliant on rainfall is extremely difficult in some rural areas, particularly in the often sparsely populated drought-sensitive arid and semi-arid areas. Not least, there are trade-offs, for example, drought-resilience versus optimisation under normal conditions; investment into production versus resilience-enhancing infrastructure; self-reliance of food production (for normal years) versus establishing food markets (during droughts); or specialisation gains (plus securing measures such as insurance or savings) versus resilience through diversification.

Implementing multi-sectoral drought policies should particularly consider the following:

- In the optimal case, there should be a general framework for disaster risk management, where specific actions against droughts, based on specific needs and characteristics, are identified. For weather-induced disasters (floods), close co-ordination with drought policies is sometimes worthwhile. Whether a standalone or embedded into a larger disaster management strategy, a strong and comprehensive co-ordinating institution is indispensable for drought management in order to enhance co-operation among the various levels of governments, development partners and non-governmental organisations.

- Drought risk management approaches must be integrated into both long-term development measures and humanitarian responses. This requires a clear understanding – by all stakeholders – of short-term disaster relief activities as well as long-term development measures towards resilience-building at community, sub-national and national levels and across many sectors. Regional and international issues should be explicitly considered. A mix of bottom-up resilience approaches that brings the concerns of farmers, civil society and grassroots together with the top-down measures (including national policy) would be optimal, the latter having to support the former (principle of subsidiarity). The Ending Drought Emergency programme in Kenya is an example of such an approach.

- Effective communication among relevant stakeholders is important for the efficient and proper functioning of early warning systems for drought. This should be tailored to long-term drought resilience and preparedness planning, better targeting and proactive action. This also has to extend to strong monitoring and evaluation and knowledge-management of drought resilience efforts and achievements.

- Flexibility of funding (contingency planning) and programmes must be built into development budgets. This means that development programmes can switch to “emergency modus” and fund emergency measures if drought is declared. Flexibility is also required within the on-going programmes. For example, the Productive Safety Net Programme (PSNP) in Ethiopia temporarily expanded during drought periods in many cases (see article on pages 32–33).

- Building the capacity of individuals, institutions and organisations, especially at the local level, is decisive to process and use, as well as to efficiently mobilise and absorb, resources.

In this way, droughts can become a “connector” and an opportunity for strengthened collaboration among many sectors, levels and actors.

Dr Daniel Tsegai is a Programme Officer in charge of “Drought and Water Scarcity" Portfolio at the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) in Bonn, Germany.

Dr Michael Brüntrup is a Senior Researcher with the German Development Institute/ Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), Bonn, and works on issues related to agriculture, food security and drought with a regional focus on sub-Saharan Africa.

Contact: michael.bruentrup@die-gdi.de

The original article has been published as "Briefing Paper 23/2017“ by DIE.

References and further reading

Anderson, C., Mekonnen, A., & Stage, J. (2011) Impacts of the Productive Safety Net Program in Ethiopia on livestock and tree holdings of rural households. Journal of Development Economics 94(1), 119–126.

Arnold C., Conway, T., & Greenslade, M. (2011) DFID cash transfers literature review. London: Department for International Development (DFID).

Ashley, S. (2009) Guidelines for the PSNP Risk Financing Mechanism in Ethiopia. Bristol: The IDL group.

Barrientos, A. (2010) Social protection and poverty. International Journal of Social Welfare 20(3), 240-249.

Béné, C., Devereux, S., & Sabates-Wheeler, R. (2012) Shocks and social protection in the Horn of Africa: Analysis from the Productive Safety Net Programme in Ethiopia (IDS Working Paper 395). Brighton: Institute of Development Studies (IDS).

Dercon, S. (2011) Social protection, efficiency and growth (CSAE Working Paper WPS/2011-17). Oxford: University of Oxford, Centre for the Study of African Economies (CSAE).

Devereux S., Sabates-Wheeler, R, Slater, R., Tefera, M., Brown, T., & Teshome, A. (2008) Ethiopia’s Productive Safety Net Program (PSNP): 2008 Assessment Report. Final Draft.

Devereux, S. (2010) Seasonal food crisis and social protection in Africa. In B. Harriss-White & J. Heyer (Eds.), The comparative political economy of development: Africa and South Asia, pp. 111-135. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Duguma, K. Mesay, Brüntrup, M., & Tsegai, D. (2017) Policy Options for Improving Drought Resilience and its Implication for Food Security: The Cases of Ethiopia and Kenya. DIE Study Paper. Bonn, Germany.

Ellis, F., White, P., Lloyd-Sherlock, P., Chhotray, V., & Seeley, J. (2008) Social Protection Research Scoping Study. Norwich: University of East Anglia, Governance and Social Development Resource Centre, Overseas Development Group.

Gilligan, D. O., Hoddinott, J., & Taffesse, A. S. (2009) The Impact of Ethiopia’s Productive Safety Net Programme and its Linkages. Journal of Development Studies 45(10), 1684-1706.

Headey, D. D., Taffesse, A. S., & You, L. (2012) Enhancing Resilience in the Horn of Africa: An Exploration into Alternative Investment Options (IFPRI Discussion Paper 01176). Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

Hoddinott, J., Gilligan, D. O., & Taffesse, A. S. (2009) The Impact of Ethiopia’s Productive Safety Net Program on Schooling and Child Labor. Draft paper. Washington. D.C., IFPRI.

Jones, N., Tafere, Y., & Woldehanna, T. (2010) Gendered Risks, Poverty and Vulnerability in Ethiopia: To What Extent is the Productive Safety Net Program (PSNP) Making a Difference? London: Overseas Development Institute (ODI).

MOA. (2014a) Productive Safety Net Programme, Phase 4. Programme implementation manual. Addis Ababa: Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia.

Porter, C. and Dornan P. (2010) Social Protection and Children: A Synthesis of Evidence from Young Lives Longitudinal Research in Ethiopia, India and Peru. Policy Paper no.1, Young Lives, Department of International Development, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment