Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

A conflict-sensitive approach is needed

Moses, a typical local farmer, lives in Morobo, located in the very South of the greenbelt of South Sudan. This region has a high potential for agriculture and food production. Rainfall above 1,200mm distributed in two rainy seasons per year and virgin clay soils render this area capable of feeding the entire population of South Sudan. As population density is low access to land is not limited. Nevertheless, Moses cultivates only one hectare of land. He mostly grows food crops, such as sorghum, maize, cassava, beans and groundnuts, on traditional rain-fed systems to feed him, his wife and five of his children – without any kind of mechanisation. He generates low yields and hardly markets any of his products. Markets are too far away, and he does not even have a bicycle. Additionally, like many others, he lacks appropriate storage facilities, and streets in the new country are in bad repair and hardly passable in the rainy season, which discourages traders to come to his village. These are some reasons for a very low income and why only one of his five children can attend a secondary school. Apart from digging his own land, he occasionally helps on other farms or produces charcoal to generate some cash.

Moses was born in Morobo, but spent half of his life in a refugee camp in Uganda, with limited access to education. In 2002, after the situation calmed down at his home land, he and his family moved back to Morobo.

The post-conflict situation in South Sudan

After nearly five decades of warfare, the new Government of South Sudan faces immense challenges in building the new state. The repatriation of citizens from exile, the diversification of the country’s oil-dependent economy, as well as securing peace within the country’s borders, are some of the major issues to be tackled. State building is still just getting off the ground.

As more than 50 per cent of all South Sudanese live in absolute poverty, and 80 per cent of the population earn their living from small-scale farming, agriculture is a strategic sector for the Government. Without appropriate investment in agriculture, it will be impossible to lift the majority of the South Sudanese out of poverty and food insecurity. However, related support institutions, like training centres and governmental services as well as private partners for potential co-operation are rare and hardly work. Educational level is low.

From self-help groups to Farmer Field Schools

In 2006, Moses and 22 other small-scale farmers formed the Alotto farmers group. Many of those groups have been built around Morobo with the aim to help each other and improve their production as well as to facilitate access to support provided by donors. Two years later, a GIZ DETA project (see Box at the and of the article) offered support based on the existing group structure and conducted a needs assessment. In 2012, Moses’ Alotto farmers group was selected, amongst others, for including it into the Farmer Field School approach (see Box below). The criteria were that the groups were easily accessible and road-connected, thus having the realistic chance of being linked to local and national markets and therefore being likely to contribute to increased national food production. In total, 26 farmers groups composed of 452 small-scale farmers, have been selected or formed, out of whom 166 are women, and organised in 13 Farmer Field Schools.

The Farmer Field School approach

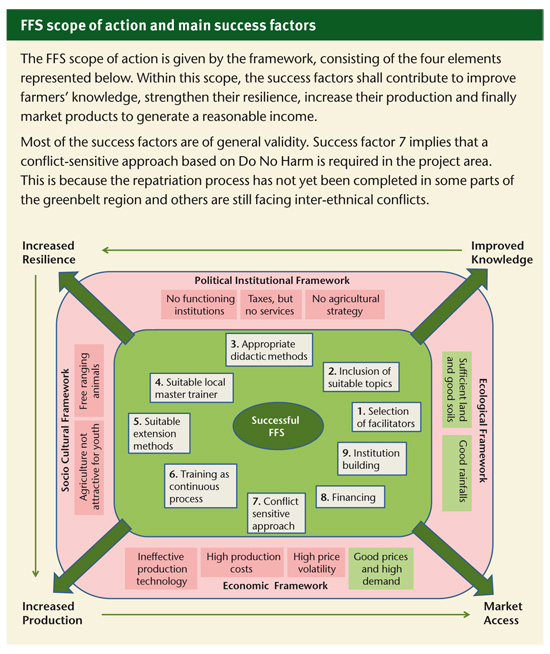

The FFS approach was developed by FAO in the late 1980s in the context of Integrated Pest Management (IPM) in South East Asia. Since this time, the concept has been further developed and adjusted to many different contexts, also considering the complexity of livelihoods. The FFS approach and its various forms (e.g. AgroPastoral Field Schools, Farmers Live Schools, Junior Farmer Field Schools) have become very popular in development work but also in transition aid. FFS is a participatory approach where group members identify topics of common interest that they want to learn about. Generally, production and marketing-related issues are covered. FFS participants combine their local knowledge with new information to adjust their referring actions. The process builds self-confidence and teaches decision-making, problem-solving and management skills.

The FFS approach in the greenbelt of South Sudan.

The concept of FFS was developed by GIZ DETA and the local government. Facilitators are in charge of training of the farmers and follow-up in the individual farmers’ fields. They are backed by the DETA project and the master trainer, the director of the Agricultural Advisory Organization, a private agency. The approach is financed by GIZ DETA, which pays facilitators a small incentive. Farmers are not contributing money to the FFS system yet.

Moses’ weekly routine and thinking has changed since the FFS was formed. Instead of just farming his private land, he meets once a week with farmers from three different groups and a facilitator on the jointly owned FFS field. The facilitator supervises group activities and contributes knowledge on state-of-the-art agricultural technologies. The topics of the FFS are mainly production oriented and include planting techniques, weeds, pest and disease management, post-harvest techniques, and soil and water conservation practices.

Furthermore, Moses is proud of acting as its secretary. He is one of only five group members who can read and write, which helped him be elected. The only literate woman has the post of treasurer. Other posts include the chairperson and the respective vice-positions. When Moses now works in his own fields, he applies what he has learned within the FFS.

First results …

FFS provides farmers with technical and organisational skills. Since Moses attended the FFS, he has tried to apply improved practices in his individual fields as well as possible and also talks about them with non-FFS participants. He very much appreciates what he has learned, such as row planting and prober spacing. He states that these techniques “have brought large effects”. He ranks row planting high because it makes weeding easier. In the past, weeding was a woman’s activity. Today Moses does it, too. During the period of the SLE study, when the first harvest after the introduction of the FFS activities was under way, Moses and other members of the group interviewed expected higher yields.

The majority of participants are highly motivated. On average, more than two thirds of the group members regularly participate in the FFS activities. Farmers have described their common interest in keeping the group together and helping and learning from each other. Access to improved agricultural practices, the increase of knowledge and the training that they are getting have finally helped them to improve the lives of their families. Nevertheless motivating the youth is still a challenge as young people see agriculture as an unprofitable occupation. Moses’ two oldest children are not keen to get engaged in farming. They grew up in refugee camps and have no connection to practical agriculture. The oldest son already lives in a city and is trying to make a living from offering taxi services using a motorbike that he has rented from a big businessman.

Moses and the majority of other farmers very much appreciate the practical approach, which is suitable for adults with a lower level of education. However, since 70 per cent of his group are illiterate, facilitators and support services are facing the challenge of finding suitable methods for dissemination of new knowledge. Furthermore, when it comes to market orientation, vulnerable people with low capacities are easily left out.

… and long-term vision

The FFS itself does not need to be sustained. However, to assure the impact of FFS, including farmers’ capacities to do farmer-to-farmer extension and to look for further knowledge providers needs further strengthening. The aim is to increase production and to strengthen the commercialisation of agricultural products by promoting appropriate storage and gradually linking farmers to markets. The goal is also to achieve self-sustained groups, through subsequent actions such as collective marketing of produce and lobbying through farmer networks, savings groups and other associations.

In sum, the FFS approach is suitable in post-conflict situations to rebuild agriculture, improve food security and sustain farmers’ livelihoods. However, when it comes to training of facilitators and the gradual handover to facilitators that are members of the FFS as well as accompanying measures such as infrastructure development and building up related knowledge, brokers are necessary to guarantee the long-term success of FFS achievements.

A key challenge for FFS for rehabilitation of agriculture is to find an appropriate balance between meeting short-term needs and the long-term desire to change. Short-term funding of donors’ engagement in transition situations is contrary to the need of fundamental changes in behaviour and knowledge transfer as well as setting up related institutions. All this requires a long-term effort.

Background of the study

Since 2008, the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) has been implementing a Development-Oriented Emergency and Transitional Aid (DETA) project in South Sudan. The project works across the three states of Greater (Western, Central and Eastern) Equatoria to support host communities, returnees, and Internally Displaced People (IDPs) in reconstructing their lives. In co-operation with the local government, GIZ DETA has been running a pilot phase of Farmer Field Schools (FFS) in the Central Equatoria State (CES) since April 2012. The goal of the FFS is to foster farmers’ productivity and market-oriented production.

GIZ DETA has asked the team of the Centre for Rural Development (SLE) to assess the pilot phase of the FFS in Morobo County (CES) for (i) potential improvements and (ii) possibilities of scaling up the GIZ DETA FFS approach to the Eastern (EES) and Western Equatoria States (WES). Data was collected in the three areas. In Morobo, ten out of thirteen FFS have provided information on their socio-economic situation and first impacts of the FFS. In EES and WES farmers groups, individual farmers and other key persons gave input to access the situation in these areas.

Further reading:

Ilse Hoffmann et al.: Achieving Food Security in a Post-Conflict Context, Recommendations for a Farmer Field School Approach in the Greenbelt of South Sudan. Berlin: SLE 2012. www.sle-berlin. de

Resources and further reading

Ilse Hoffmann, Lloyd Blum, Lena Kern, Enno Mewes, Richard Oelmann: Achieving Food Security in a Post Conflict Context, Recommendations for a Farmer Field School Approach in the Greenbelt of South Sudan. Berlin 2012.

Download: https://edoc.hu-berlin.de/docviews/abstract.php?lang=&id=40071

Enno Mewes, Ilse Hoffmann

SLE – Centre for Rural Development

Humboldt University Berlin, Germany

sle@agrar.hu-berlin.de

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment